The Only Remaining Alternative

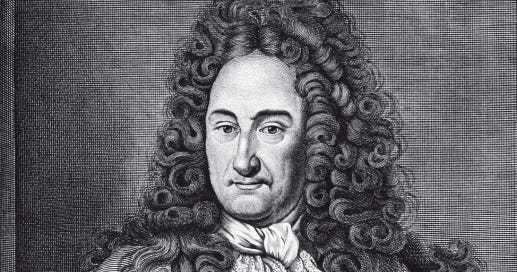

Leibniz, Classical Theism, and the Problem of Evil - Chapter 8 (3 of 3)

Greetings, subscribers. As followers of Theological Letters know, I spent much of this last year writing a forthcoming book on Leibniz and the problem of evil, and I have been posting fresh installments from that work every Sunday.

To date, I have posted the Introduction and all of Part I — Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and the first two parts of Chapter 8. Today, I post the final installment of Chapter 8 and thus of the book.

If you have yet to read all that comes before, I recommend you do so for context. Links to all prior sections are below. Enjoy!

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

The Only Remaining Alternative

Throughout this work, I have made consistent references to classical theism. Leibniz’s antecedents and influences largely presume a transcendent deity, who is the optimal being, with his infinite perfection being reflected in the classical attributes of omniscience, omnipotence, omnibenevolence, and other omnis. From these commitments arise the premises that are so difficult to escape concerning God’s Goodness, Wisdom, Justice, and Power. As we have seen, those who remain within the broad confines of classical theism have a great deal of trouble evading Leibniz’s conclusions. If, however, one is resolute on rejecting the theory of the best, there is a more extreme escape route available, namely, abandon classical theism altogether. Might this tactic — that is, abandoning classical theism for a not-so-classical theism — offer a road out of optimism? In this, our final section, we will consider two representative examples in order to assess the viability of this final exit.

The first example we will consider is the objective idealism of G. W. F. Hegel, one of the more well-known post-Leibnizian idealists. Hegel’s not-so-classical theism (or more accurately, pantheism) is perhaps best set against the contrasting backdrop of the classical Great Chain of Being. As discussed at length in Part I, classical theism tends to see our world as a hierarchy of beings, stretching from the least godlike (rocks and plants) to the most godlike (humans and angels). Transcending the heights of this hierarchy is God, who is pure, unchanging perfection. And (presuming a classical substance metaphysic) beneath the lowest regions of being, percolating at the fringes of non-existence is prime matter — a substratum of pure potential that does not even rise to the level of a concrete entity.

I find this backdrop useful because Hegel essentially inverts the traditional thinking about God and world as conceived in this classical vision. Hegel’s idealism begins by collapsing God and world, embracing a form of pan(en)theism.1 But this pan(en)theism does not reflect the impulse toward necessitarianism that we find in Spinoza, building from a classical conception of God to the necessity of the world he produces. Rather, for Hegel, God bears every possible perfection, but his optimal nature is only implicit, like DNA. As a result, the various perfections of God are collapsed into an unarticulated undercurrent, without division or differentiation. For these perfections to be explicit (rather than implicit), God must articulate his perfections in finite beings, finitizing himself by unfolding his optimal nature into a world.2

Lest we think of this self-actualization as volitional, Hegel further clarifies that ontological perfections are not the only things that require finitude. “Consciousness … is a differentiating, a division within itself,”3 says Hegel. By way of implication, God is neither conscious nor self-aware apart from his self-expression in the world. He becomes conscious and self-aware in and through the creatures he produces. Thus, the divine movement from implicit to explicit — or, in classical terms, from potential to actual — is simultaneously God’s act of creation, his movement toward self-actualization, and his development of self-understanding.4 As Eric Rust explains, “history and nature are to be understood in rational terms as objects of that dialectical process in which the Absolute spells itself out in time and without which the Absolute would be ‘lifeless, solitary, and alone’.”5

The vision is notably different from classical theism. The divine nature is optimal but not in any concrete sense. For the divine nature is unarticulated until it becomes concretely real in the production of a world. The process itself awakens God, making him conscious and self-aware in and through the creatures he generates. God does not look to the best or to any other end; he does not consider a set of possible worlds or how best to construct reality. Rather, he himself unfolds, the divine Spirit becoming self-aware in this self-actualization.

If an escape from optimism is possible, then something along these lines certainly seems promising. By dispensing with divine consciousness, self-awareness, and choice prior to the creative process, perhaps we can dispense with the sorts of notions that drive so many toward the best — namely, that God makes considered choices about the world.

A second, more recent alternative to classical theism is process philosophy — yet another brand of panentheism.6 Like Hegel, there is an integration of God and world into a common developmental vision. The view rejects the classical divine attributes — or at least the classical formulation of these attributes. God is neither perfect nor optimal in the classical sense. In other words, classical theism tends to ascribe to “perfect being theology,” which presumes there is a conceivable, abstract, and stable optimal Being — in knowledge, in goodness, in perfection, and so on. Process philosophy rejects this notion.7 For example, God is not omniscient in the sense that there is a set body of knowable truths that God knows a priori. Rather, as concrete reality grows and evolves, so does God’s knowledge. And similar claims emerge with reference to divine power, goodness, beauty, and so on.8

Applied to Christianity, and specifically biblical theology, the view accepts a great many things that classical theism looks at as problematic. Process philosophy accepts the narrative of divine suffering and struggle between God and Israel in the Old Testament and thus has no difficulty embracing the suffering of the Son of God in the New Testament.9 When considering developments and changes in the Old Testament Law and the further developments in New Testament morality, process thought neither looks to a Marcionite theory of two deities — the evil deity of the Old Testament and the good deity of the New Testament — nor does it strive for systematic coherence, reconciling seemingly irreconcilable claims. Instead, it accepts the evolving nature of God and world reflected in God’s dealings with his creatures throughout history.10

Such an option, like Hegel, is far more radical than the proposals of Stump, or Hick, or Adams, or Swinburne. Unlike Hegel, we have divine consciousness and choice that leads to the creation of the world, but the concept of God is very unlike the classical picture. So, do such alternatives escape Leibniz? I’m unconvinced they do.

Hegel’s pan(en)theism unquestionably evades the idea that God considers a host of possible worlds and chooses the best. Less clear, however, is whether Hegel avoids something approaching the Stoic version of the theory, discussed in Chapter 5. Recall that the Stoics conflate God and the cosmos, which leads them to conclude that every cosmic cycle is identical. For God can be neither better nor worse, so the cosmic cycles can be neither better nor worse. Hegel speaks about contingency in the world, but it’s unclear how his view leaves room for it — this being a common critique of his position by staunch free will advocates.11 If what unfolds is the articulation of God’s implicit perfections, and if we grant that God is the optimal being (even if only implicitly at first), then what unfolds is the highest. From what I can tell, Hegel’s theory seems to require something like the Stoic conclusion: Our world is the best because it is the articulation of the best — that is, of God. The theory is not Leibniz’s brand of optimisms, to be sure, but Hegel’s theory does not provide a prime facie escape from optimism of some kind.12

In this light, even Hegel is not extreme enough. It may be that the only real escape from Leibniz is to abandon the optimal nature of God altogether. For this, we must look to process thought, which explicitly rejects the classical attributes. So, considering this alternative, does process offer a means of evading optimism? Truthfully, I find even this escape dubious.

Although process philosophy rejects the traditional omnis, process philosophers still identify God as optimal in some sense. For example, Charles Hartshorne says in his rejection of divine perfection, “God then cannot change for worse. The view I wish to defend admits this.”13 Yes, Hartshorne says that change for better is possible for God. And yes, he rejects the concept of an optimal being in the Anselmian sense.14 But despite this, he admits that God is relatively optimal:

The divine, to be worthy of worship, must excel all conceivable being other than itself: it must be unsurpassable by another, exalted beyond all possible rivals. Hence all may worship God as in principle forever superior to any other being.15

Here, I cannot help but see the theory of the best reasserting itself. Let’s grant that God’s benevolence can grow, his knowledge can grow, and so his wisdom in how he providentially cares for our world can also grow. Despite this growth, Hartshorne tells us that God is still unsurpassed in goodness, knowledge, and wisdom. There is, then, a sense in which God’s dealings with mankind reflect his optimal nature. His knowing and doing reflect the best possible understanding and judgments. “Best possible” takes on a relative sense, of course: No other being could have known better or judged better. But God’s judgments remain unimpeachable, and God’s will is a reflection of his optimal goodness, knowledge, and wisdom. In short, God always does the best that can be done, given the state of reality.

What we see in these examples, then, is that the theory of the best continues to reassert itself, even in these more extreme alternatives to classical theism. What precisely it means to say that God always does the best changes, to be sure. Theories of foreknowledge and middle knowledge fall away. But what does not fully disappear is some form of optimism, some conviction that God, being optimal, performs or produces the optimal — whatever that might mean within the given worldview. The only escape route I see is something far more extreme, namely, to deny the omnis in both the objective and the relative sense. In other words, grant that God is fallible and corruptible, like the pagan gods of old. Only in this way can one say that his judgments are like ours, reflecting desires, understanding, judgments, and choices that may not be best, choices that are, in fact, impeachable. This, it seems, would be the only viable road to a rejection of optimism. But such a rejection, put bluntly, entails denying the very divinity of God.

Allow me one final consideration before I close. Leibniz is a child of Western Christianity. Eastern Christianity harbors considerable differences in its view of God, especially in its distinction between God’s essence and his energies and how this unfolds into a very different perspective on divine simplicity and the other divine attributes.16 Might Eastern Christianity, with its distinct brand of theology, offer its own escape from Leibnizian optimism?