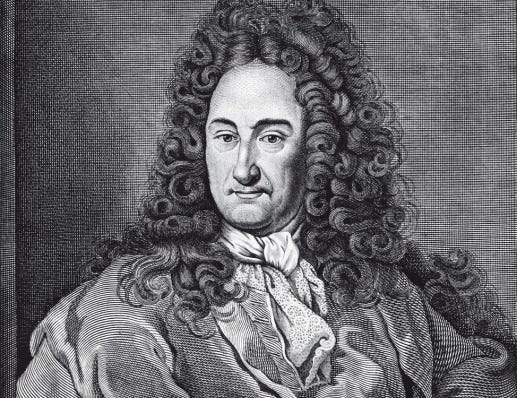

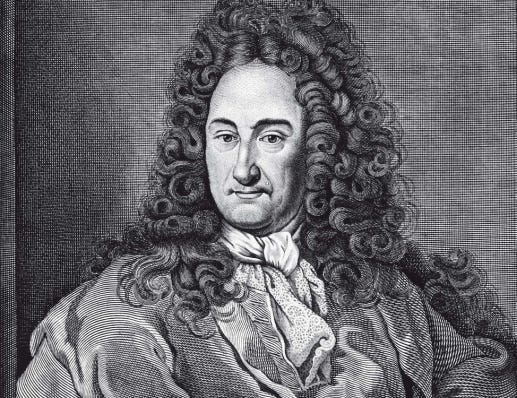

Greetings, subscribers. As followers of Theological Letters know, I recently finished my forthcoming book on Leibniz and the problem of evil, and I have been posting fresh installments from every Sunday.

To date, I have posted the Introduction and all of Part I — Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, and Chapter 4. Today, I post the first installment of Part II, with Chapter 5, Optimism Before Leibniz.

If you have yet to read all that comes before, I recommend you do so for context. Links to all prior sections are below. Be watching for the second installment of Chapter 5 next Sunday. Enjoy!

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

Optimism Renewed

Optimism Before Leibniz

For Him who is supremely excellent it neither was nor is permissible to perform any action save what is most beautiful.1

— Socrates

In 399 B.C., in a remote Peloponnesian town, Echecrates greets a traveler, Phaedo of Elis, a friend and pupil of the famed Socrates. Word has reached Echecrates that the philosopher is dead, having ingested hemlock in his cell after being sentenced to death by the state of Athens.2 Eager to hear about his final hours, Echecrates bids Phaedo to tell him all. So, the loyal disciple recounts his teacher’s final dialogue with a small group of friends before the Wisest of Men departed the flesh.

The Phaedo dialogue explores several topics, most notably (and understandably) the immortality of the soul, meant to tell us Socrates’ impending fate. Yet, within this dialogue, Socrates recounts something else, easily passed over. He recalls once hearing someone reading a work by Anaxagoras, one of the earliest pagan philosophers. In those pages, Socrates heard an exceedingly formative claim: All things are ordered by “mind” (νοῦς). The notion pleased him. As for its implications, here is how Socrates recounts his understanding:

“I once heard someone reading from some book — of Anaxagoras, he claimed — and asserting that it is Intelligence that organizes things and is the reason for everything. This explanation pleased me. Somehow it seemed right that Intelligence should be the reason for everything; and I reflected that if this is so, in the course of its arrangement Intelligence sets everything in order and arranges each individual thing in the way that is best [βέλτιστα] for it. Therefore if anyone wished to discover the reason why any given thing came, continued, or ceased to be, he must find out how it was best [βέλτιστον] for that thing to be, or to act or be acted upon in any way.”3

In these words, we see something surprisingly common amongst ancient writers. Providence (πρόνοια) is the belief that the world is ordered by a divine Mind. And with this appear two further assumptions, tacit in the earliest writers and explicit in later ones: God is Good and, indeed, the Highest Being. The implication is precisely what Socrates concludes. The Highest, bearing Mind and Goodness, must order all things in the best way.

In other words, the so-called “optimism” of Leibniz is far from a Modern invention. Like so many things that we find in the philosopher of Leipzig, the theory that God always does things in the best possible way is the Leibniz’s inheritance, not his invention. Yes, Leibniz develops the concept in ways that go well beyond his predecessors, as he is apt to do. But the theory of the best finds ample precedent before him. And as we will see, this precedent also reveals that the challenges to divine freedom — and by extension, human freedom — have equal precedent within this tradition. But like Leibniz, his predecessors refuse to concede the death of liberty, groping to find a way to preserve what they believe to be true of God without relinquishing what they also believe to be true about free choice. So, in our effort to explore whether Leibniz might be rescued from the jaws of necessity, let us begin our revisitation of Leibniz, not with the philosopher of Leipzig, but with those who set the stage for his optimism.

Optimism and Evil in Pagan Thought

At the dawn of pagan philosophy, several questions occupy the landscape: Is the world created or uncreated? Does anything truly come to be or pass away? Is our world governed by providence? The early outliers on such questions were the Epicureans, who held that the world is uncreated, nothing truly comes to be or passes away (the atoms merely reorganize), and the cosmic “order” is unguided chance.4 What set these early atheists5 apart was not their belief that the world is eternal. — Plato alone believed there was a start to time, Aristotle tells us.6 — Nor was it that generation and corruption is just a rearranging of substance. — Empedocles, too, believed change is just the mingling or dissolution of the elements, and the Eleatics likewise thought it was logically necessary that nothing comes to be or passes away.7 — No, what set the Epicureans apart was their denial of providence, that is, the belief that no Intelligence governs our world. Hence, all change, (apparent) order, generation and dissolution are unguided happenstance.

Already mentioned was Anaxagoras, who taught that mind is not solely a feature of the human animal but pervades all of nature, “as the cause of the cosmos and of all its order.”8 Like the atomists, Anaxagoras thought there is no true coming to be or passing away. Generation and destruction is just the mingling and dissolution of enduring, eternal particles. But unlike the atomists, Anaxagoras taught that these material processes are not matters of chance. Material order is orchestrated by something immaterial — by Nous, a divine intelligence that transcends the material world but nonetheless organizes and orders it.9

Although several names would be given to this divine orderer of nature, the view was far from novel. Aristotle tells us that Hermotimus of Clazomenae held the same before Anaxagoras.10 Heraclitus, likewise, speaks about the divine “Word” (λόγος), which pervades and orders the material realm.11 Empedocles speaks about the four elements mingling to produce the cosmos, and this orderly mingling is orchestrated by a divine being, who he names “Love” (φιλότης).12

If there is a dispute amongst these early advocates of providence (aside from what constitutes the building blocks of reality), the dispute is whether there is a start to this ordering. Anaxagoras speaks of a beginning, when Nous first moved, setting the particles in order.13 Heraclitus, by contrast, describes a cyclical cosmos, with neither beginning nor end; yet, this ever-moving order is infused by the Word (λόγος), an ever-living fire that is also ever-moving.14 Empedocles offers a third option — cosmic cycles. The four elements mingle to form our cosmos by the coaxing of Love, but then the cosmos is dragged into disorder and dissolution by the cosmic enemy of Love — what he names Strife (νεῖκος) — only to repeat this cycle.15

These primitive theories grow more sophisticated with Plato.16 Plato’s view of providence builds on his theory of the Forms and its distinction between being and becoming. Plato recognized that, when encountering an object, the mind reflexively tries to identify what it is — dog or cat, square or circle, bipedal or quadrupedal, and so on. Equally reflexive is the mind’s assessment of its quality, whether it is good or bad, well-formed or malformed. Plato’s theory begins from the question, To what is the mind referring when doing this? When naming a geometric shape “circle” and saying it is a poor one, the mind is evidently comparing the shape to something else. But what? The answer, Plato concludes, is that the mind is comparing the object to the very idea of circle — not the idea of this circle, but of circle per se or ideally.

Alongside this insight, Plato makes a second observation about the distinction between the material object and the idea against which we measure it. The archetype is not only ideal but unchanging. The material instance, by contrast, is subject to time and change, improvement or dissolution. And so emerges Plato’s theory of the Forms.

Plato suggests that the archetypal ideas by which the mind knows and measures reality are themselves real in some sense. These archetypes he names “the Forms” (τῆς Μορφῆς).17 On the traditional reading of Plato, his theory is that there are two worlds, the world of the Forms and our material world. The Forms are the realm of being — of unchanging stability, of perfection, of the idyllic archetypes to which the mind refers when judging an object. Our material world is a moving picture of the Forms — a place of shifting replicas and approximations of these archetypes — and these material replicas are subject to flux, generation, and corruption. So how does the soul know the Forms? It evidently does, given the reflexive habits of mind. But how and why? Plato answers simply, the soul is from the world of the Forms. It beheld them before migrating into a material body. So, when encountering shifting realities, the soul draws on memory, comparing the material object with the Forms to determine which archetype it best approximates — as well as judging the quality of the approximation.18 This bifurcated reality sets the stage for Plato’s creation myth.

In the Timaeus, Plato weaves a “plausible tale” of how our world came to be. So the story goes, God’s Goodness is the starting point for creation.19 He desired all things to be good and as near to perfection as possible. Or more precisely, God “desired that all should be, so far as possible, like unto Himself,”20 for he is the most excellent (ἄριστος).21

Critical to the tale is that God is not a creator of matter. He is the Demiurge (δημιουργός), or craftsman of the material realm. Alongside God sat a second principle, the uncreated material void, unstructured and disorderly.22 In his Goodness, God wished for matter to be something more, to display greater excellence and goodness, to take on order and structure. So, “finding the visible universe in a state not of rest but of inharmoniously and disorderly motion, He brought it into order out of disorder, as he judged that order was in every way better.”23

Here, the divine mind (νοῦς) comes into play. Goodness impels the Demiurge to bring order to matter, and his rational nature is what makes him capable of doing so.24 Therefore, the Demiurge searched for the best model for his craftsmanship, and he found it in the object of his own rational contemplation, namely, the eternal Forms.25

The Forms enter the story, not as static shapes, but as parts (many of them alive) that comprise a much larger character — what Plato calls the “absolute Living Being.”26 And here emerges an important insight into Plato’s thought. The world, according to Plato, is a living creature, and of this one creature each of us is part, like a cell within a larger body. The Form, human, contains within it sub-Forms (e.g., eye), which contain further sub-Forms (e.g., animal cell), which contain further sub-Forms (e.g., golgi body), and so on. Likewise, the Form, human, is a sub-Form within the Form animal, which is a sub-Form within the Form living, and so on. In short, the world is one living animal.27 And so it is with the Forms, which compose the absolute Living Being, the archetype after which our material cosmos is modeled.28 Therefore, the Demiurge, impelled by Goodness and equipped with reason, raised matter from disorder to order, crafting a moving picture of the absolute Living Being.29 Such is the beginning of our world.

Saturating this narrative is Plato’s conviction that our world is best. God wishes all things to be as like him as possible, and God is best (ἄριστόν).30 God wishes all things to be good and free of imperfection, as far as possible,31 and the absolute Living Being is the best model for the visible world.32 When describing the Demiurge’s reasoning, Plato describes a dialectic of which is better — living or not-living, rational or not-rational.33 In every instance, the Demiurge is impelled by the pairing of Goodness and Intellect toward the better. And to all of this Plato adds the maxim: It is impossible for the Highest Being to do anything but the best.34 So, the insight that Plato first gleaned from Anaxagoras proves true: We can be sure “the reason why any given thing came, continued, or ceased to be” is that it was best (βέλτιστον).35

Subsequent Platonists carry on this tradition. Middle Platonism explicitly echoes Plato’s narrative: God desires all things to be as like himself as possible, he being the best of all causes. And along with this narrative, they echo Plato’s connection between God and the best.36 NeoPlatonism, likewise, traces the cause of the world to the convergence of divine Goodness, Intelligence, and the Forms. Far from weakening the connection that we find in Plato, they strengthen it. For they identify Demiurge fully with Nous, and the Forms that offer the ideal model for our world are located, not outside God in a separate character (the absolute Living Being), but within God, as the very contents of the divine Mind.37

Within these later Platonists, we also discover the burgeoning concern to defend the optimal nature of God’s handiwork, despite whatever evils might blemish it. Their namesake, Plato, had already set the stage for the most common defense. God is the Highest Being, and the Forms are the best model. The restraints on perfection are located in two things, which operate independent of God. The first, to no surprise, is matter.38 The second is creatures to whom God has given free will — “what is up to us” (τὸ εφ ἡμῖν) — this being a small scale reproduction of God’s own power of will.39 The latter explanation plainly arrests responsibility for defect from God, since it admits that rational beings have the power of self-determination, which can thwart God’s will. As for matter, the Platonists tend to identify this second principle as chaotic and inherently unstable, which is why it fails to perfectly represent the Forms. We can see this when Plutarch, for example, identifies matter, not as a passive recipient of form, but as an active principle that interferes with the works of God.40 In either case, evil has its source in things that are not God, for God only ever does what it is best.

Within this proto-optimism, we find two further developments that anticipate later queries. The first concerns divine choice. Plato’s plausible tale suggests that the absolute Living Being is the best model available to the Demiurge. Does such a claim tacitly admit that there were other, less ideal models? Plutarch denies the conclusion. The optimal perfection of the world remains, whether produced by contrary choice or by necessity.41 Here, we see the NeoPlatonic impulse to ascribe will to God but to redefine such a term in reference to God as a lack of constraint, rather than as contrary choice.42 We also see perhaps the earliest marks of optimism leading to the abandonment of divine freedom, though this impulse does not yet encroach on the contrary choice of creatures — as we see both in the explanation of evil and in one further development.

This second development concerns providence. More specifically, does God’s care over this optimal world include its events and ongoing governance or merely its initial production? The replies are mixed amongst later Platonists. The Middle Platonic picture of God is of a legislator who delegates responsibility to lower beings — to gods, the World Soul, and demons.43 And given such delegation, Plutarch accepts that there is a level of indeterminacy in the world. Hence, we might compare God to a prophet who foretells future events without being directly responsible for them.44 In NeoPlatonism, however, we find resistance to even this level of providence. Plotinus rejects any suggestion that God employs any amount of foreknowledge or calculation of future contingencies in his dealings with the world. Why? This would not only make God a spectator of the realm of becoming but also distract from his pure contemplation of the Forms.45 The reply appears to be a reiteration of Plato, who suggests that the Demiurge returns to contemplating the Forms after fashioning the world, thus making “the best” a description of the world system, not its history.46

Despite whatever variations we might find in the philosophical offspring of Plato, several commitments are ubiquitous. God is the Highest Being. His production of the world springs from a desire for all things to be as like him as possible, since he is optimal perfection. The pairing of Intelligence and Goodness is what impels God to do so, his Goodness being the root of this desire to bring things into order and his Intelligence being what makes him capable of doing so. The Forms, which are the ideal object of his own contemplation, provide the archetype for the task of raising matter up from disorder into order. And if any defect is found in God’s handiwork, it is traceable, not to God, but to matter and to creatures who resist the Highest Being’s effort to produce the best.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise that the proto-optimism of Plato echoes in those who carry his mantle. But what of Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle? Do we find in Aristotle any hint of his teacher’s optimism? At first blush, we may expect a negative reply. After all, the traditional view is that Aristotle denies divine providence.47 However, there is reason to think that such a judgment would be premature.

Let’s begin with why Aristotle is typically thought to deny providence. His theology, as mentioned in prior chapters, builds on something like the argument from contingency, where all things come to be, and this coming to be rests on something that does not come to be. Hence, God is an “Unmoved Mover,” who moves things (into being) without ever moving (into being).48 Why would this mean he is not provident? Because Aristotle recognizes that to perceive change is to undergo change. If I watch you raise your right arm, then the image of you within my mind shifts by means of perception. So the traditional reading goes, Aristotle’s God thinks, not on the world — lest he change with it by perception — but on himself, the perfect, unchanging object of his thought.49

Some today argue that Aristotle’s philosophy allows for more direct divine activity than this reading admits.50 And there are notable features of his thought that support the point. — For example, Aristotle critiques Empedocles for ascribing ignorance to God, which indicates that Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover must know all things in some sense,51 even if only by comprehending them by comprehending himself as their First Cause.52 Also, though Aristotle says that God is the final cause of the world, he still identifies God as an agent (ποιητικός),53 which opens the door to God moving things in a more direct way than typically supposed. — However, one hardly needs to dispel the traditional reading in order to show that Aristotle presumes some form of providence and that the best is the basis for the world’s formation.

Let’s begin with how a God who does not think about the world moves it. The answer requires that we consider two points at which Aristotle diverges from his teacher, Plato. The first is the Forms. Aristotle rejects Plato’s theory that Forms exist outside of matter as a second world. Instead, Aristotle forwards his well-known theory of hylomorphism. Unlike Plato’s material void, Aristotle posits a theory of “prime matter” (ἡ πρώτε ὕλη), which is an ontological middle between nothing and something.54 Matter, in this sense, is a substratum of pure potential in which form manifests, producing a hylomorphic (matter-form) composite. Perhaps the best way to conceptualize the theory is to imagine fabric and a solid object. The fabric is amorphous with the potential to take on any number of shapes. Were we to drape the fabric around a ball, the fabric would become spherical; were we to drape it around a cube, it would become cubical, and so on. Yet, neither sphericality nor cubicality belong to the fabric per se; it belongs to the ball or the cube that communicates sphericality or cubicality to the fabric, supplying it with shape. In the same way, matter, as pure potential, or “non-being” (μή ὄν), is without innate properties of its own, but its potentiality is the potential to take on properties, concretely manifesting form. On this theory, then, form never exists independent of matter. Rather, form exists within matter as the cause of its formation and movement, form being what moves material potential (δύναμις) into concrete actuality (εντελέχεια) or being.55

Perhaps for this reason, Aristotle concludes that the soul itself is the form of the body, the soul’s movements being the very thing that drives bodily formation, structure, and activity56 — a fact that will prove critical moving forward. And keep in mind that every living thing bears a soul. Not all have reason, but to be alive is to be ensouled (ἔμψυχος).57

The second place where Aristotle diverges from his teacher is on the immortality of the soul. Plato believes the soul is eternal.58 Aristotle believes it originates in time.59 Now, because there is a start to the soul’s movement, on Aristotle’s account, the soul requires a mover. And here we approach the answer to how God moves the world. Aristotle suggests that all psychic movement originates from desire for some good.60 Desire moves the soul, and the soul, in turn, moves the body, which is the material expression of the soul.61 From this Aristotle concludes that God is the one who moves the soul,62 and thus by moving souls, he also moves the material world by desire. Why? Aristotle’s answer appeals to his tenth category, passion. According to Aristotle, just as a man is moved by desire in the presence of a beautiful woman, so God, the Highest (ὕπατος), moves the world as the object of its yearning love.63