For those who follow Theological Letters (thanks to all of you), you know that I have been posting a four-part series on the history of predestination. Three of four parts are posted (part 1, part 2, and part 3), but unfortunately, I need to take a brief detour into another topic before posting part 4.

I’m presently in Greece on set of a television series on which I am writer and co-Executive Producer — a time-consuming venture in its own right. But I’m also up against a literary deadline. I have a forthcoming book on Leibniz with Routledge. Longtime followers of Theological Letters may remember me posting about this back when I was first writing the volume (here). Well, my revised and finish manuscript is due at the end of April, and I have yet to make my promised revisions. (Hopefully, no one from Routledge subscribes to my substack!) So I need to turn whatever non-television writing time I have toward that book.

Toward that end, I will welcome all of you, dear subscribers, into my writing world. You can hold me accountable. I commit that as I finish a chapter, I will post it here for all of you to read. In the coming weeks, you can anticipate an Introduction and six chapters on the classical theism, problem of evil, and Leibniz’s theodicy.

I encourage even those who are uninterested in Leibniz to read the volume. For the book is much more for classical theists, philosophers of religion, and folks interested in the problem of evil generally than it is for Leibniz scholars specifically. And like my Theological Letters, my goal is to strike a tone that is accessible, despite the difficult material.

So, with that, we begin with my Introduction to Leibniz, Classical Theism, and the Problem of Evil: Why Classical Theism Must Affirm That Our World Is the Best of All Possible Worlds.

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

Introduction

All Nature is but Art, unknown to thee;

All Chance, Direction, which thou canst not see;

All Discord, Harmony not understood;

All partial evil, universal good;

And Spite of Pride, in erring Reason’s Spite,

One truth is clear, WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT.

— Alexandar Pope1

On November 1, 1755, faithful Christians of Lisbon gathered for mass on All Saints Day. Sounds of morning worship filled the sanctuary. Then, suddenly, a new sound arose beneath the chorus — the rumble of an earthquake. The very walls that echoed with worship of God moments earlier collapsed, killing the faithful inside. The whole of Lisbon was razed to the ground. And on the heels of the horrific event followed a tsunami, fires, and civil unrest. Thousands died. News of untold devastation spread across Europe, raising in the minds of many a common question. Why would God allow such evil?

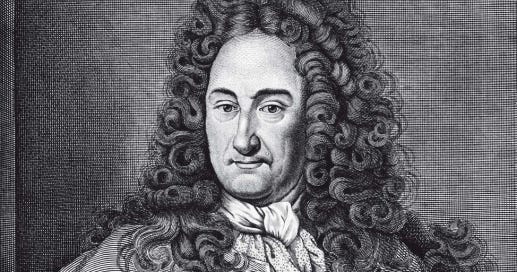

In the wake of the devastation, French poet and philosopher, Voltaire, began work on a satirical story, Candide, ou l’Optimisme (Candide, or the Optimist).2 The would-be classic relentlessly mocked the “optimism” of famed rationalist G. W. Leibniz (1646-1716). Leibniz had (in)famously argued in his Essais de Théodicée (Essays of Theodicy)3 that our world is the best of all possible worlds, a “best” that includes the innumerable and unspeakable evils that God permits. Voltaire highlights the apparent absurdity of the theory with the story of Pangloss, a teacher of metaphysico-theologo-cosmolonigology, who is charged with the education of a young man named Candide. As Pangloss and Candide explore the world together, the two are beaten, tortured, maimed, starved, and burned. But through it all, Pangloss parrots the brilliant Leibniz. It is all for the best.

Voltaire’s cynical take on Leibniz’s theory is far from an outlier. Most who encounter his defense of God, or “theodicy,”4 find it absurd on the face of it. How could a world full of theft, rape, murder, war, disease, tyranny, and daily atrocities possibly be the best of all worlds? Surely, the prevention of even one evil would make our world better, and such prevention must certainly be within reach of an omnipotent Being. This is not to say that God is without his defenders — certainly not. The defenders of God’s Goodness and Justice in the face of evil are many.5 But the defenders of Leibniz and his theodicy are few.

Despite the unpalatability, if not apparent absurdity, of Leibniz’s optimism, I do not believe his conclusion is so easily dismissed. Quite the contrary, I think his theodicy may prove to be inevitable for adherents to classical theism — and even for many not-so-classical theists. I will make this case in the pages to follow by laying bare Leibniz’s reasoning, by showing its precedent in both pagan and Christian thought, and by revisiting his claims in the light of such influences, offering a novel rereading of his case that, in my humble opinion, corrects ubiquitous misunderstandings of his philosophy generally and his notorious theodicy specifically.

In chapters 1 and 2, I set the stage for my revisitation of Leibniz. I, first, show how his rather startling theory follows from his commitment to the Principle of Sufficient Reason and its pairing with the classical theism of both Latin Christianity and its pagan predecessors.6 The former compels Leibniz to trace every contingency to God, and the latter leads him to conclude that God always does the best. Hence, the reason our world exists is because it is the best of all possible worlds.

Before tackling the nearly reflexive impulse to usher forth a parade of evils as counter evidence, I pause to consider precisely what Leibniz believes is best about our world. Here, we discover echoes of another classical theological tradition, which sees being as good and evil as the privation of goodness. In accord with this tradition, Leibniz understands the best, or optimal, world to be a world that maximizes goodness by maximizing the being within it. But like so many things within Leibniz’s thought, this traditional starting point expands considerably in the philosopher’s hands, as he offers his own peculiar account of substance and causality in order to multiply exponentially the goods of our world.

Despite Leibniz’s best efforts to depict our world as saturated with unending goodness, the question remains: What of evil? With the philosopher of Leipzig’s optimism laid bare, I explore the ways in which he strives to reconcile his startling conclusion with the reality of evil in our world. Leibniz names three kinds: metaphysical evil, physical evil, and moral evil. When speaking about the goodness of our world, Leibniz expounds a number of complexities surrounding the will of God, complexities that show how the decisions of providence are more complex than objections from evil admit. Bringing these same complexities to bear on the realities of evil, we see how Leibniz reconciles the Goodness and Justice of God with the presence of evil in our best of all possible worlds.

Putting aside the difficulty of swallowing the pill of optimism — which is no small challenge — the theory naturally raises a worry. If every being and every event proceeds from divine design and is meticulously selected because of its indispensable place within the optimal blueprint, then perhaps every aspect of our world is absolutely necessary and could not be otherwise. Regrettably, Leibniz’s peculiar theories of substance and causality (in addition to his theories about true propositions) in no way assuage the worry. Far from it, his views amplify the fear to a near certainty. So, after establishing the bases for Leibniz’s theory of the best in chapters 1 and 2, I trace the contours of this rather irksome problem in chapter 3, showing why Leibniz’s philosophy generally and his theodicy specifically are so often thought to threaten both divine and creaturely freedom, stripping from God and his creation the power of contrary choice, leaving us inextricably woven into a nexus of endless necessities.

With the theory and its problems before us, I set my hand to work at a fresh rereading of Leibniz. In chapter 4, I begin with some important but largely ignored context for Leibniz’s optimism, namely, the philosophical and theological antecedents of his theory. Throughout chapters 1 and 2, I highlight a great many antecedents to Leibniz’s thought concerning God and world, many (though not all) of which are well known. But in chapter 4, I expand this backdrop considerably into largely untilled soil. Specifically, I explore the ample precedent for the theory of the best amongst ancient and medieval advocates of divine providence, both pagan and Christian alike, stretching from Plato (5th century BC) to John of Damascus (8th century AD). As I demonstrate, Leibniz’s theory of the best is far from an outlier in classical theism. Whatever idiosyncrasies the philosopher of Leipzig may harbor — and there are many — this is not one of them. Hence, scandalous though Leibniz’s “optimism” may be, the theory of the best is far from his invention. And in these writers, we also find many of the same problems for divine and human freedom that emerge for Leibniz.

The point is instructive for two reasons. First, though the problem of freedom is certainly real for proponents of the best, neither the theory of the best nor its problems should be laid at Leibniz’s feet. Second, when considering what precisely Leibniz is claiming in his theodicy, we would do well to attend to his predecessors on the road to optimism.

In chapter 5, we reach the most novel feature of my reading of Leibniz. There, I examine the near-universal assumption that Leibniz is a determinist, an assumption that factors heavily into how his theodicy is read by modern scholars. Once again, I begin with neglected context from the classical theist tradition of which Leibniz is part, and in doing so, I offer reasons to think this standard assumption is false. I set the stage by showing several incoherencies that emerge in Leibniz’s thinking if the determinist reading is correct. Certainly, one might conclude that such incoherencies are real, being an artifact of unsolvable problems created by conflicting commitments in the philosopher’s thought. However, I treat such problems as a reason to explore whether a libertarian reading of Leibniz is possible. My exploration begins with a notable flaw in contemporary scholarship. To wit, the case for Leibniz’s determinism is based in no small part on his rejection of “freedom of equipoise.” That is to say, most modern readers treat equipoise as synonymous with libertarian choice. Yet, ample precedent exists in Leibniz’s theological influences for rejecting equipoise while defending libertarian freedom — the latter being rooted in the “spontaneity” of the will paired with reason, which Leibniz unquestionably advocates. The point is especially noteworthy when considering that this tradition includes figures who are arguably amongst the main influences on Leibniz’s thought.7

With this backdrop in mind, I highlight the many ways Leibniz echoes such influences, not only in his talk of free choice but even in his conception of possibility and contingency. By revisiting Leibniz’s texts in the light of this theological tradition, I bring to light a host of new interpretive avenues for his discussion of freedom. More specifically, I show how this tradition allows his seemingly deterministic claims to be coherently read in harmony with this libertarian tradition and demonstrate how such a rereading resolves otherwise unresolvable tensions in Leibniz’s thought. As we will see, such an interpretation radically transforms Leibniz’s claims about divine and creaturely freedom, answering the worries about determinism outlined in chapter 3 and making his claims about God, freedom, and evil far more palatable.

Having crafted new lenses by which to peer at the philosopher of Leipzig, I take a fresh look at Leibniz’s theodicy in chapter 6. Granting the case of the prior chapter, I recast Leibniz’s theodicy under the assumption that he harbors a libertarian view of freedom and show how such a commitment would color his claims about possible worlds, free choice, and the best. Unlike the typical worries about a determined God who produces a necessary world filled with horrors that is somehow best, Leibniz-reread offers a far more dynamic theory of possible worlds and divine choice, which preserves not only God’s freedom but creaturely freedom and the dynamic interplay between the two amidst the unfolding drama of history. Such dynamism offers a very different perspective on what it means to say our world is the best of all possible worlds, offering a more satisfying explanation of how evil might find its way into the best of worlds. The end result is a theodicy wholly unlike the common caricature mocked by Leibniz’s opponents.

With this revised theodicy before us, I look, in chapter 7, at alternative answers to the problem of evil amongst modern philosophers of religion. Time and again, I show that these contemporary defenders of God universally reject Leibniz’s theory of the best — often with prejudice. Yet, in forwarding their alternative, they offer a theory that is compatible with Leibniz-reread, if not a full recapitulation of his reread-theodicy. In short, I show that neither the alternatives to Leibniz’s theodicy nor the alternatives to the best succeed in escaping the Leibnizian case. Hence, in the end, I conclude that Leibniz’s theodicy looks to be inevitable for not only classical theism but even for many not-so-classical theisms.8

Now, before delving into the meat of this work, I should offer a clarification about my thesis. When saying I believe Leibniz’s theodicy is inevitable, I do not have in mind the suppressed clause, “in all its specifics.” Leibniz unquestionably harbors a great many idiosyncrasies that are far from inevitable for classical theism. His theory of substance (the monadology) and causality (pre-established harmony) are two such examples. And such doctrines proliferate into a host of additional idiosyncrasies, such as how Leibniz defines “existence,” his theory of knowledge, his take on necessary and contingent truths, his views on identity, and his understanding of the plenitude of goodness in our world. By no means do I intend to suggest that such idiosyncrasies are inevitable for classical theism. Certainly not.

Leibniz unquestionably believes such theories are commended by the theory of the best, a fact that will become evident as we proceed. But such idiosyncrasies, in my assessment, are accidental to his optimism. Why? The answer is this. Were we to catalog the bricks that comprise the road to optimism, we would discover something like the following:

The Principle of Sufficient Reason, or the notion that every truth has a reason why it is so and not otherwise.

The search for reasons sufficient to ground contingent truths (and perhaps necessary truths) leads back to God, who is the foundation of all truth.

From the concept of God’s perfection follows the conclusion that God only ever does what is best.

The Goodness of God and an examination of good and evil point to the same conclusion, namely, that being is good (or a positive reality) while evil is a privative phenomenon (or the negation of some original good).

God articulates his own Goodness in the act of creation by filling up the world with a diverse array of beings, stretching from the most humble to the most sublime, each of which articulates in its own unique way some aspect of God’s perfection.

This Chain of Being, as it is sometimes called, is part of what it means for God to do the best when creating the world: To wit, filling up the world with a maximal expression of the goodness of being in a harmonious whole.

Though we often say casually that “God can do anything,” the classical conception of omnipotence understands the law of contradiction to have its grounding in God, and thus contradictions are beyond even an omnipotent Being, representing confused ideas that are not possible in any meaningful way.

Because contradiction is beyond the bounds of omnipotence, God must often forgo goods that he wills or permit evils that he wills not, either because certain goods conflict with one another (incompossibility) or because certain goods and evils enmesh with one another (concomitance).

The Goodness of God requires that God only ever will good and repel evil, which is why God only ever permits evil, never willing it affirmatively.

The nature of God, therefore, leads us to conclude both that our world is the best of all possible worlds and that the evils within it attach, not by divine pleasure, but by divine permission due to the complexities of incompossibility and concomitance.

As will become clear throughout our exploration, none of the above commitments are unique to Leibniz and, thus, in no way depend upon his idiosyncratic doctrines. Yes, at every turn, Leibniz wishes to fill up both the road to optimism and the best with more and more material. He expands on the Principle of Sufficient Reason in ways that go beyond his predecessors; he strives to “complete” the ontological argument in his own peculiar ways; his enthusiasm for filling up the Chain of Being with as much good as possible leads him to commend his odd theories of substance and causality; and these theories expand the notions of incompossibility and concomitance beyond what was contemplated by his predecessors. But in all such matters, Leibniz is populating well-trodden territory. Neither the road to optimism nor the conclusion of the best requires such fillers, which is precisely why I see such idiosyncrasies as accidental, rather than essential, to his case.

For this reason, I am far less concerned with Leibniz’s idiosyncrasies than with the more classical contours of his claims. To be sure, I will give due attention to the Leibnizian particulars when fleshing out his theodicy in chapters 1 and 2, when highlighting in chapter 3 the worries about how optimism generally and his spin in particular threaten freedom, and when offering a rereading of Leibniz on free choice in chapter 5. But I will treat these idiosyncrasies as precisely that, idiosyncrasies in his overall case for the best that are non-essential to my case that optimism is the inevitable conclusion of the classical theist.

Where Leibniz’s idiosyncrasies are indispensable is in my attempted rereading of his theory of freedom — a fact I do not deny. But this brings me a second point about the present work. I do not believe the success of this volume hangs entirely on the success of my rereading of Leibniz. Yes, I believe I rightly identify reasons to think that Leibniz’s theory of freedom has been misread and the result has been an undue suspicion of his theodicy. But let us say that my rereading fails — or simply fails to persuade, even if correct. I do not believe the value of this work evaporates. To the contrary, whether the revisitation of Leibniz is truly Leibniz or a pseudo-Leibniz of my own invention, the result is still an alternative theory of the best that commends itself to the classical theist. Yes, I believe the optimism I present in the pages to follow is true to the philosopher of Leipzig. But even if one disagrees, then the vision presented here nonetheless represents a proposed theodicy worthy of consideration, be that proposal credited to Leibniz or to me.

So, with that, we stand at the threshold of the task at hand. But before stepping over this threshold, indulge a final word about target audience and tone. The danger when writing a book of this kind is that it walks a narrow road with a ditch on either side. On the one side is the risk that those who are not Leibniz scholars will quickly pass over the volume on the presumption that this is a book solely for specialists. Yet, make the work too accessible to non-specialists and a new danger emerges, the risk of losing Leibniz scholars who presume it is an introductory text with nothing to offer the field of Leibniz studies.

Narrow though the road may be, this work strives to offer much to specialists and non-specialists alike. For the former, the contents of this volume, if taken seriously, require a seismic shift in Leibniz studies. In addition to highlighting largely ignored antecedents to Leibniz’s theory of the best specifically and his philosophical theology generally, this work highlights a near universal assumption about Leibniz’s view of freedom — namely, that his rejection of equipoise is a rejection of libertarian choice — and demonstrates that this ubiquitous interpretive assumption is erroneous, a fact that requires a reassessment of all that Leibniz builds upon his theory of freedom, which is to say, everything.

For the philosopher of religion, philosophical theologian, or even arm-chair intellectual who wades into the waters of the problem of evil or the relationship between divine and human freedom, the claims of this volume are no less significant. For the pages to follow unearth a tradition concerning divine providence that pervades the ancient and medieval worlds and proves exceedingly difficult to avoid under the presumptions of classical theism — and even when traded for the presumptions of not-so-classical theisms. This tradition culminates in Leibniz but is largely ignored because of it, given how maligned his theodicy has been. Yet, the fact remains. Leibniz’s optimism is not his invention but his inheritance, passed down by some of the most revered pagan and Christian thinkers of the pre-Modern world.

Hence, both specialists and non-specialists have much to consider in the pages to follow. For better or worse, then — or perhaps for the best — I have tried to walk this narrow road, making the contents of this volume maximally accessible to non-specialists without abandoning the goal of making very real contributions to Leibniz studies. And the result I offer to you, dear reader, in the hope that, whichever you are, you will benefit.

Alexander Pope, Essay on Man (Upsala: L. G. Berglund, 1799), 11.

M. de Voltaire, Candide, ou l’Optimisme (London, 1759).

The full title of the work is Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal (Essays of Theodicy on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil), which Leibniz published anonymously in 1710. The 1716 Latin edition, published just after Leibniz’s death, is the first edition to include the philosopher’s name on the cover. The work can be found in G 6:25-436. English quotations in this volume use the E. M. Huggard translation.

The term “theodicy” was coined by Leibniz and is taken from the Greek words θεός (God) and δίκη (justice), indicating a defense of the justice of God in the face of evil.

The works dedicated to answering the problem of evil are too vast to catalog here. We will explore several contemporary replies in chapter 6, including Alvin Plantinga, The Nature of Necessity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974); Alvin Plantinga, God, Freedom, and Evil (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1977); Eleonore Stump, “The Problem of Evil,” Faith and Philosophy 2 (1985), 392-424; Eleonore Stump, “Providence and the Problem of Evil,” in Christian Philosophy, ed. Thomas P. Flint (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1990), 63-7; John Hick, Evil and the God of Love (London: Macmillan, 1985); Marilyn McCord Adams, “The Problem of Hell: A Problem of Evil for Christians,” in Reasoned Faith: Essays in Philosophical Theology in Honor of Norman Kretzmann, ed. Eleonore Stump (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), 301-327. Some additional defenses in contemporary literature include Ninian Smart, “Omnipotence, Evil, and Supermen,” Philosophy 36, no. 137 (1961): 188-195; Peter Van Inwagen, “The Problem of Evil, the Problem of Air, and the Problem of Silence,” Philosophical Perspectives 5 (1991): 135-165; Peter Van Inwagen, Christian Faith and the Problem of Evil (Grand rapids, MI Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2004); Richard Swinburne, “Some Major Strands of Theodicy,” in The Evidential Argument from Evil, ed. Daniel Howard-Snyder (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996): 30-48; Gregory Boyd, Satan and the Problem of Evil: Constructing a Trinitarian Warfare Theodicy (Lisle, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2001); Richard Swinburne, Providence and the Problem of Evil (Oxford University Press, 1998); John S. Feinberg, The Many Faces of Evil: Theological Systems and the Problems of Evil (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2006); John G. Stackhouse, Can God Be Trusted?: Faith and the Challenge of Evil (Lisle, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008).

The predicate “Latin” is meant to distinguish the commitments of Christianity in the Latin West from the commitments of the Christian East amongst Greek, Syrians, and others. Leibniz plainly situates his own theology within this tradition in a number of places, including his Examen religionis Christianae.

I have in mind here the Reformed scholastics generally, which includes the Herborn encyclopedists, a group Leroy E. Loemker has argued are one of the main influences on Leibniz. See Leroy E Loemker, “Leibniz and the Herborn Encyclopedists,” Journal of the History of Ideas 22:3 (1961): 323-38.

t the close of this volume, I include an appendix, which looks at how Leibniz answers four theological problems, namely, the problem of the Fall, the problem of original sin, the problem of Hell, and the problem of predestination. Throughout this volume, and especially in the closing chapter, I highlight a misconception about Leibniz’s theodicy, namely, that he offers an exhaustive account of the reason for evil. This misconception has led some contemporary defenders of God to distinguish their “defense” from a “theodicy,” the former being a demonstration that evil and God are logically reconcilable, without offering any commitments on why God permits evil, while the latter offers a complete account of the reasons for evil. See, e.g., Plantinga, God, Freedom, and Evil, 28. Yet, as we will see, Leibniz offers no such account. Quite the contrary, he is driven by his a priori understanding of God to the hypothetical necessity that if God makes a world, then it is the best of all possible worlds. From here, he shows only that evil is logically compatible with this conclusion, leveling no specific commitments on which of his various solutions are in fact correct. By Plantinga’s definitions, then, Leibniz offers a defense, not a theodicy. — One would need to look to John Hick’s Evil and the God of Love, for example, to find a theodicy as defined in these terms. — My appendix aims to highlight the method by which Leibniz handles theological problems, exploring various solutions without landing on specific commitments.

Thank you very much Dr N Jacobs. Thoroughly enjoying this, despite how much is stretches my thinking patterns :)

How embarrassing for me. I thought you wrote a type when you wrote "Leipzig." haha. Leibniz is from Leipzig.