Divine Freedom and Possible Worlds

Leibniz, Classical Theism, and the Problem of Evil - Chapter 6 (4 of 4)

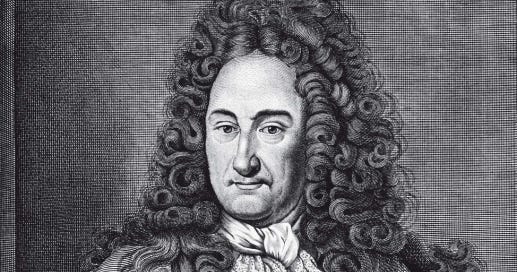

Greetings, subscribers. As followers of Theological Letters know, I spent much of this last year writing a forthcoming book on Leibniz and the problem of evil, and I have been posting fresh installments from that work every Sunday.

To date, I have posted the Introduction, Chapters 1-5, and the first three installments of Chapter 6. Today, I post the fourth and final installment of Chapter 6, In Search of a Libertarian Leibniz.

If you have yet to read all that comes before, I recommend you do so for context. Links to all prior sections are below. Be watching for the first installment of Chapter 7 next Sunday. Enjoy!

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

Divine Freedom and Possible Worlds

The above considerations offer a pathway to libertarian freedom within Leibniz’s system for creatures. However, the case is less compelling in reference to God. In the case of God, we have seen only one alternative to the best — non volo, which makes divine inaction possible, such that the best might not exist. But is this the sum total of divine freedom? Choose or withhold choice?

Surprisingly, the answer may be no. The fact that Leibniz draws on voluntarist resources may open the door to other possibilities. To see how, let’s consider his view of possible worlds.

Let’s begin again with a common presumption about the philosopher of Leipzig. He is typically read as a Molinist because of his talk of possible worlds.1 Molinism is famous for its advocacy of “middle knowledge” (scientia media), a knowledge of hypothetical futurities or counterfactuals. The view is so named because it proposes a “middle” between God’s necessary knowledge and his free knowledge.

By way of background, scholastics before Molina (and before other advocates of middle knowledge, such as Francisco Suárez)2 suggest that God has two types of knowledge. The first is necessary knowledge, which concerns necessary truths. Here we find mathematical and geometric truths, as well as logical truths concerning the essence of things, such as the will being a self-determining faculty. Free knowledge, by contrast, concerns contingent truths that depend on the will of God. If, for example, God determines to make a world that includes a first man named Adam who resides in a place called Eden, then this future truth is freely known by God. Now, as for what grounds God’s free knowledge, we saw in the previous chapter that the intellectualists and voluntarists disagree on the answer.3 But whatever the basis for their grounding, there was general agreement that God’s knowledge fell into these two categories.

Molinism, however, posits a third type of knowledge that sits between God’s necessary knowledge and his free knowledge, namely, middle knowledge. Now, notice that necessary truths concern abstract realities (except in the case of necessities about God himself) while free knowledge concerns concrete realities — the contingent truths of our world. Molinism posits something in between, hypothetical truths about what would be if. According to Molinism, the balance between freedom and providence is found in these hypotheticals. God is provident over the future, but providence chooses from foreknown hypotheticals about creaturely choices, thereby balancing the sovereignty of God over history with our free choices.4

Without question, Leibniz agrees that God has knowledge of possible futures that will never come to be. But does this suffice to make him a Molinist? No. Keep in mind the above point: Middle knowledge sits between God’s necessary knowledge and his free knowledge. This fact raises one of the main objections to middle knowledge. Either God knows something necessarily or freely; there is no middle. So which is it? Does God necessarily know these hypotheticals? Or does he choose to know them? The complaint of many scholastics is that Molinism wants it both ways. On the one hand, God just knows hypothetical futurities, which seems to make them necessary. On the other hand, these futurities concern free choice, which makes them contingent. Much like Molinist equipoise, many deemed middle knowledge incoherent, positing a chimerical fiction.

So, does Leibniz advocate middle knowledge? From what I can tell, the answer is no. We can point to at least two places where he explicitly rejects Molinism. The first is his essay, “Middle Knowledge” (A 6.4.1373-4). The piece offers an intriguing objection to Molinism. If equipoise is true, then the explanation for a choice can never be found in the chooser. For the chooser’s will is essentially indifferent to all its choices, even at the point of choosing. Were this the case, then God’s knowledge of the chooser cannot yield knowledge of its choices. To know its choices, God must observe them. In other words, if equipoise is true, then God cannot have a priori knowledge of futurities. He must have a posteriori knowledge of futurities. And this, Leibniz knows, is utterly contrary to the traditional view of omniscience. So, he rejects middle knowledge.

Now, as noted in the previous section, the essay is quite an early one. So we might wonder if Leibniz changes his view. But his comments in Theodicy also indicate a rejection of middle knowledge, which is where we find a second critique in his account of the predetermination dispute (G 6:125-6). The “predeterminators,” as Leibniz calls them, represents the Thomist position within the concurrence debate, discussed in chapter 3.

Recall the backdrop of Suárez’s exploration of general concurrence. The Thomist position identifies God as First Cause and the creature as the secondary cause, arguing that the secondary cause has no power to act except what is supplied by the First Cause. Hence, the First Cause must “premove” the secondary cause, and this premotion applies the secondary cause to its “predetermined” effect.5 We saw Suárez’s worry that the Thomistic account makes God the Author of evil and destroys free will.6 But what is the predeterminator’s objection to middle knowledge? According to Leibniz, the predeterminators oppose middle knowledge because its hypothetical futurities posit creaturely action independent of God’s will. Why? Because middle knowledge, according to the Molinists, is “pre-volitional” — these hypothetical futurities finding their way into the divine Mind without any act of will by God.7 So the criticism goes, then, such hypotheticals conceive of creaturely action prior to any divine choice to support such action, which is impossible.

So where does Leibniz come down on the dispute? He finds truth on both sides. To no surprise, he believes the predeterminators are correct that contingent truths are contingent upon God. So, with the predeterminators, he insists that creaturely action must be conceived with the ground for its possibility, namely, God’s predetermination — “the choice of a creature is an act which essentially involves divine predetermination, without which it is impossible for that choice to be exercised” (C 23). But Leibniz is sympathetic to the worry, leveled by Suárez, that predetermination of a certain kind makes God the Author of evil. So he qualifies predetermination to avoid this consequence: “My opinion is that it must be taken as certain that there is as much dependence of things on God as is possible without infringing on divine justice” (C 22; see also G 6:199-203; 339-40; 344; 383-4; 347-50). The reference to divine justice, of course, concerns Leibniz’s insistence that God produces whatever is ontologically positive in the creature, any defect being a product of creaturely imperfection and resistance to God (C 22; G 6:347-50). The resulting theory of predetermination is one in which God foreknows the creature’s free choice and his predetermination accommodates this choice: “God understands perfectly the notion of this free substance, considered as possible, and from this very notion he foresees what it choice will be, and therefore he decides to accommodate to it his predetermination” (C 22-3). So, on this front, he agrees with the predeterminators.

Where Leibniz disagrees with the predeterminators is the conclusion that God does not have hypothetical knowledge. Like the Molinists, Leibniz identifies three types of truths that God knows: the general possibility of things (rerum possibilitatem), what is in fact actual (quid actu existat), and what would exist contingently, granting certain conditions (certis positis esset) (C 18). However, because the third category deals in conditionals with their requisite conditions — one of these being God’s predetermination — the resulting theory of hypothetical futurities is not the middle knowledge of the Jesuits. Hence, Leibniz differentiates his view from both positions: “For this result [i.e., showing truth on both sides] I resort to my principle of an infinity of possible worlds” (G 6:126/H 146).

If, however, these possible worlds are not the futurities of Molina, then what are they? A clue emerges, again, in his essay on middle knowledge. After explaining why Molinism must say God’s knowledge is a posteriori, Leibniz goes on to describe the proper relationship between God’s will and God’s knowledge. Regarding the actual, God knows what he has decreed, and regarding conditionals, he knows what he would decree under those conditions. He then credits Scotus with the insight that the divine intellect knows things at the determinations of the will (A 6.4.1374).