Predetermination, Freedom, and Possible Worlds

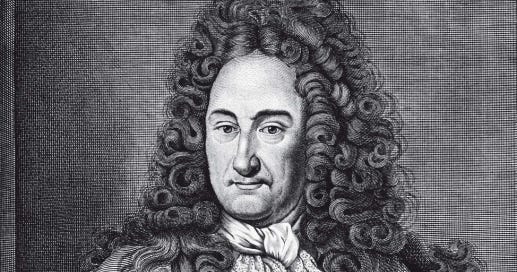

Leibniz, Classical Theism, and the Problem of Evil - Chapter 7 (2 of 3)

Greetings, subscribers. As followers of Theological Letters know, I spent much of this last year writing a forthcoming book on Leibniz and the problem of evil, and I have been posting fresh installments from that work every Sunday. My apologies for letting yesterday slip through the cracks! Better late than never, I suppose.

To date, I have posted the Introduction and all of Part I — Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and part 1 of Chapter 7. Today, I post the second installment of Chapter 7, Leibniz’s Theodicy Redux.

If you have yet to read all that comes before, I recommend you do so for context. Links to all prior sections are below. Be watching for the first installment of Chapter 7 next Sunday. Enjoy!

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

Predetermination, Freedom, and Possible Worlds

So much of Leibniz’s theodicy hangs upon the logical limits of omnipotence and the free will of creatures. The facts of concomitance and incompossibility not only provide the basis for divine choice but also the lather by which to wash evil from the hands of God: Not even God can bring about every good or prevent every evil. And yet, this claim is intimately tied with the concept of freedom. For Leibniz does not make evil or suffering part of the original fabric of the world. But within our world lives rational beings, beings capable of turning away from God and ushering sin into creation, and with sin suffering and death. We are the ones who have tilted the world off its axis.

Although the traditional reading of Leibniz struggles tremendously to find any justification for so robust a freedom as this, our prior chapter made the case that Leibniz can preserve free choice — a critical step in upholding his defense. Yet, a troubling matter still looms. Having embraced the notion of possible worlds, can Leibniz really preserve so strong an appeal to free will? With this question, I do not mean to reintroduce the specter of determinism. Rather, I raise a different question. If every logical possibility is represented in the realm of the possibles, then can we really say that freedom limits divine choice the way Leibniz suggests? Is there no world in the realm of the possibles in which Adam does not sin? in which rational beings do not plunge the world into wickedness, corruption, and death?

To address this question, we will reconsider Leibniz’s theory of possible worlds. More specifically, we will look at his theory in the light of stance on predetermination, paired with our libertarian hypothesis. Bringing these two considerations to bear, we have reason to think that Leibniz’s possible worlds are not so easily conflated with logical possibilities, as the question presumes.

Let’s begin with a refresher on divine concourse and predetermination. In keeping with his scholastic predecessors, Leibniz is of the mind that contingent beings are inherently dependent. Or as Aquinas puts it, “all beings apart from God are not their own being, but are beings by participation.”1 Hence, creaturely dependence upon God is not a one-time affair at the dawn of existence but a matter of ongoing dependence. To use the more technical scholastic distinction, God’s causation of creatures is not per accidens, such that he prompts our existence, after which we persist autonomously, but is per se causality, an ongoing causality by which God upholds our existence at every moment.2

Amongst Christian philosophers, the concept gave rise to the doctrine of divine concurrence, according to which God “runs alongside” (concursus) creation, supplying existence to creatures at every moment.3 Or as Leibniz characterizes the doctrine, the “conservation” of creatures is a “perpetual creation” of the agent (H 125). As contingent, creaturely existence is inherently deferential, requiring God to conserve our existence at every moment (G 6:342/H 354).

Such a conclusion was the very thing that gave rise to the worry about God’s participation in evil. That is, even if we can legitimately speak about God permitting evils of which he does not approve, does not the doctrine of divine concurrence require that God directly participate in every evil act? The problem, and its solutions, long pre-dates Leibniz4 — a fact of which he is well aware (e.g., G 6:124-30/H 144-50). As we saw, despite the chorus of voices within the discussion,5 the various models tend to divide along Dominican, Scotist, and Jesuit lines,6 with Leibniz giving particular attention to the Dominican-Jesuit dispute over predetermination.

As we saw, the core of Leibniz’s own solution, while not fully aligned with either party, comes closest to the theory of the Jesuits. Looking to Suárez, for example, we saw the Jesuit worry over the Thomist model of divine concurrence. In particular, Suárez worries that the Thomist understanding of the relationship between God as First Cause and the creature as secondary cause, who is premoved and predetermined by God, makes the creature a mere instrument. In other words, either God’s act of premotion and predetermination is redundant, since the creature is fully capable of executing the act performed, or God’s contribution goes beyond the powers of the creature, making God the Author of the act and robbing the creature of contrary choice.7 In the case of evil acts, the latter makes God the author of evil and robs the creature of moral culpability, since he has no freedom to do otherwise.8

To be sure, Suárez does not deny the need for divine concurrence, and he is willing to accept the standard scholastic commitment to the idea that God is the First Cause of creaturely action, supplying premotion and predetermination to the creature as secondary cause.9 Such is not the question. The question is how God can concur in creaturely operations — especially evil ones — without authoring the act or robbing the creature of free choice? In answer, Suárez offers his theory of general concurrence. Central to the theory is that concurrence does not supply powers alien to the creature’s nature. Rather, God moves the creature in accord with its native abilities. The balance between nature and supernature, then, is within the conditional: If the creature exists and is conserved, then he can exercise these native powers (nature). But his existence and conservation depends wholly on God (supernature).10 God, thus, operates “remotely” in the secondary cause, while the creature produces the particular effect by the exercise of his own natural powers11 — in the case of rational creatures, the power of self-determination.12 Hence, both God and the creature share in one act.13

In the case of sin, however, two elements are key. The first has already been touched on — the creature has the natural power of self-determination, which opens the door to sin when housed within a corruptible being. The second, again, concerns the privative nature of evil. Because sin is a defect, which has no substantive reality of its own, this defect does not require divine production. For evil is not a substantive reality. Hence, whatever is ontologically positive in the act is traceable to God, but whatever is privative — the defect that corrupts the act in the production of evil — falls entirely to the creature.14

As noted in Part I, the general contours of this solution won the day in the post-Reformation era, even amongst those who took issue with Jesuit theology.15 Hence, we find the same line of argument in Reformed thinkers, such as Johannes Maccovius, illustrates the solution with the analogy of a man pushing a horse with a broken leg. As Maccovius explains, if we ask why the horse is moving, the answer is the man is pushing it. But if we ask why the horse is limping, the answer is the defect in its leg.16 Just as in Suárez, God is the source of what is ontologically positive in the act via concurrence, while the creature contributes the defect. Hence, God does not morally concur in the act, only ontologically.17

We found this same line of explanation in Leibniz. He frames the concurrence debate as dividing along Dominican and Jesuit lines (G 6:124-30/H 144-50), and believes the Jesuits are right to be suspicious of the Dominican view.18 But, like Suárez, Leibniz does not believe this means predetermination is wrongheaded. To the contrary, Leibniz plainly advocates the doctrine: “contingent things, and especially free substances, depend in their choice and operation on the divine will and predetermination” (C 22). However, Leibniz offers a key qualification: “My opinion is that it must be taken as certain that there is as much dependence of things on God as is possible without infringing on divine justice” (C 22, emphasis added). Note that Suárez’s worry is the same: The Dominican view assigns too much dependence to God, so much that it makes God the Author of evil and robs the creature of free choice and moral culpability. Hence, Leibniz’s position, though advocating predetermination, echoes what we find in Suárez: God supplies whatever is ontologically positive in the act, while the defect (sin) belongs to the creature alone, marking its resistance to God (e.g., G 6:383).

Recall that Leibniz’s own illustration of this relationship is of a river coursing beneath various ships, many of which move sluggishly because they are heavy-laden. Much like what we find in figures like Maccovius, the contours of the analogy are straight forward. God represents a cause of motion — in this case, a river. But some aspect of the thing moved colors the motion, introducing a defect — in this case, the cargo that retards the movement of the ships, causing them to move sluggishly in comparison with the river beneath them (G 6:120-1/H 140-1). As in other post-Reformation scholastics, the point is this. God supplies whatever is positive in the act, while the creature supplies the defect by its resistance to God.

Now, notice the centrality of contrary choice to this model of divine concourse and predetermination. The central worry, contra the Dominican model, is that the creature has no power to do other than the effect which is predetermined by God. To preserve moral culpability, then, the creature must be solely responsible for the moral defect, including having the power to do otherwise. Of course, one could accept the model on determinist terms, arguing that the creature bears a nature that inevitably goes wrong, and so, God moves the creature in accord with its nature, but this does not mean the preservation of contrary choice. Rather, it means that God supplies the ontological undercurrent for the creature to do the only deed it would ever do, given its determination. However, the Jesuit and post-Reformation use is not of this mind. One of the evident worries about the Dominican model is that the creature cannot do otherwise; hence, the creature is robbed of freedom and moral responsibility. In a word, the concern is libertarian.19

For this reason, the post-Reformation descriptions of predetermination are inherently accommodating. We see this, for example, in Gisbertus Voetius. Recall that Voetius, like his teacher, Franciscus Gomarus, rejects equipoise as a chimera but nonetheless insists that true freedom requires libertarian choice that satisfies PAP.20 The concern for self-determination of this kind makes its appearance in the description of predetermination. In the interest of ensuring that the creature’s freedom is preserved, Voetius employs a subject-object relationship, such that God knows how the creature would have moved itself independently of God, and thus, God accommodates that choice in his act of predetermination: “the predetermination turns the will sweetly and nevertheless strongly to that very end, to which it — certainly being moved and premoved by God — would have turned itself.”21

Much like the way Leibniz’s view of concurrence mirrors these post-Reformation scholastics, so his description of predetermination echoes their notion of accommodation, God foreseeing the choice of the agent and accommodating this choice in his predetermination. For example, Leibniz says in NCT, “God understands perfectly the notion of this free substance, considered as possible, and from this very notion he foresees what it choice will be, and therefore he decides to accommodate to it his predetermination” (C 22-3). And again,

I grant that when God decides to predetermine the mind to a certain choice because he has foreseen that it would choose in this way if it were admitted to existence, he foresees also his own predetermination and his own decree of predetermination — but only as possible; he does not decree because he has decreed. (C 23)

In this second statement, we see two things. The first is God’s accommodation of free choice. And lest there be any doubt, Leibniz is explicit that God accommodates even those choices that violate his will, “that is, in sin, without being the originator of the sin, and even without being accessory thereto. He does this by permitting it justly, and by directing it wisely towards the good” (G 6:162-3/H 182-3). Granting the possibility that Leibniz harbors libertarian commitments, like the post-Reformation scholastics he echoes, such accommodation indicates that the creature harbors libertarian powers of choice, God foresees what the creature will freely choose, and God permits this choice by accommodating it in his predetermination, even if he disapproves of the choice.

The second thing we see is the two acts of predetermination, mentioned in the prior chapter. Because Leibniz insists that creatures are essentially dependent, their very possibility requires divine concurrence. Hence, even in the realm of the possibles, God foresees possible creatures with his possible predetermination — since they are not possible without it. Now, we could read this language in a strictly logic sense. That is, because a contingent being requires predetermination, its logical possibility entails the divine ground of its possibility. But Leibniz’s language appears to be far more ontologically robust than such a reading admits.