Choosing Other than the Best

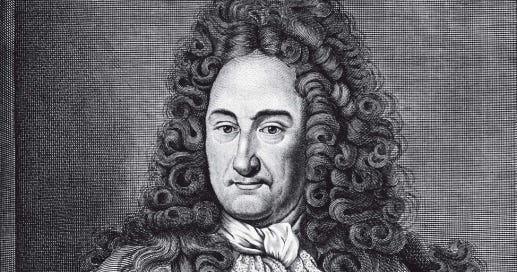

Leibniz, Classical Theism, and the Problem of Evil - Chapter 8 (2 of 3)

Greetings, subscribers. As followers of Theological Letters know, I spent much of this last year writing a forthcoming book on Leibniz and the problem of evil, and I have been posting fresh installments from that work every Sunday.

To date, I have posted the Introduction and all of Part I — Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and part 1 of Chapter 8. Today, I post the second installment of the final chapter, Chapter 8, The Inevitability of Leibniz.

If you have yet to read all that comes before, I recommend you do so for context. Links to all prior sections are below. Be watching for the first installment of Chapter 7 next Sunday. Enjoy!

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

Choosing Other than the Best

A number of philosophers have taken aim at the theory of the best in recent years. The goal, it seems, is to undermine the theory in order to make way for alternative bases for divine choice. In other words, many recognize the ways in which the theory threatens divine freedom. Hence, in the interest of liberating God from necessity and arguing for more genuine divine choice, the theory comes under harsh scrutiny. So, in the interest of a fair assessment of Leibniz’s optimism, and whether an alternative to it exists, let us consider these objections to the best.

The first objection comes from Robert Merrihew Adams. He calls into question the cogency of a “best possible world.” His case, in short, argues that there is no limit to the number of possible worlds — logical possibilities being endless. For this reason, there can be no optimal or best possible world.1 We saw something similar to this in Aquinas’ soft optimism. Recall that Aquinas believes there is no maximal creature: “Yet God could make other things, or add something to the present creation; and then there would be another and better universe.”2 This lack of a ceiling to created realities, then, means there can be no optimal world.

For my part, I am unconvinced this case holds water. The argument appears to contain a category error, conflating number and quality. Even if one grants that there is an infinite number of possible worlds, it does not follow that there is an infinite ascent of quality. In a very different context (i.e., whether the damned might make moral progress without ever attaining blessedness), Leibniz employs an analogy from geometry that is equally useful here. He writes, “Even so there are asymptote figures in geometry where an infinite length makes only a finite progress in breath” (G 6:279/H 294). The example illustrates that one can pair an infinitude — in this case, length — with a finite limit — in this case, progress. Surely the same could be true in the case of possible worlds. There may well be a limit to the quality or goodness a world can obtain, despite there being an infinite number of possible worlds.

Second, the objection very casually moves from logical possibility to an infinitude of possible worlds. As we have seen, however, Leibniz does not conflate logical possibles and real possibles. And when we consider his claims concerning real possibles, we have reason to think there are not nearly as many possible worlds available to God as the objection supposes.

Two considerations from the previous chapters illustrate the point. First, if we entertain the model of possible worlds argued above, then the number of worlds available to God plummets in comparison with the logically possible. Granting, for example, that our world plays out only once in the realm of the possibles, then there is only one version of our world available to God But there are an infinite number of logical variations of that one world, none of which are actualizable — to use Plantinga’s language. Second, if we grant a more voluntarist view of the grounding of possibles, as argued by Scotus, then there are only as many possible worlds as God chooses to generate. As argued in our thought experiment on this point, this could be one possible world or trillions. But once again, the number is not predetermined by mere logical possibility. There are only as many possible worlds as God chooses to generate.

This last point offers its own solution to the objection. Admittedly, Leibniz speaks about God producing an “infinitude” of possible worlds. As noted in the context of his voluntarist conception of possible worlds, the language is likely hyperbolic, meaning something more like “countless” rather than an actual infinity. So, let’s imagine that after generating seemingly endless possible worlds, God finds several of equal value. Under the Thomistic assumption that there is no maximal creature, God could produce one more world that exceeds these several, giving him a best possible world and thereby ending the equilibrium.

Now, perhaps one might reply by invoking my own rebuttal against me: What if there is a ceiling to the quality a world can have? Then God cannot simply produce a world of greater quality, since he has hit the limit. In this case, a different solution presents itself. Granting such a ceiling, I presume that God knows that ceiling before generating any possible worlds — he does not “discover” the ceiling by experimentation. Granting the point and granting that there are only as many possible worlds as God chooses to generate, God could avoid such equilibrium by never generating more than one world at this maximal quality. In either scenario, a best possible world is available to God.

Now, there is a second version of this objection, which the above reply stumbles into. Rather than arguing that the infinitude of possible worlds means there is no best, as Adams contends, this objection admits a ceiling to created goodness. But granting that there is such a ceiling, and granting an infinity of possible worlds, more likely than not, multiple worlds hit that ceiling. This version of the objection appears in Swinburne — as well as Mackie, Michael Banner, Joshua Hoffman, and Gary Rosenkrantz.3

Now, this criticism raises its own difficulty of divine choice, namely, on what basis does God choose a world if several are equally good? And this question has led a number of scholars to look for procedures by which God could rationally select a world, despite the absence of a best option — efforts we will consider below.4 But for now, let’s consider the objection.

As noted, we have already stumbled into the proposed scenario in the above thought experiment and offered one possible solution: Granting that there is a ceiling to created goodness, I presume that God knows this ceiling, and can avoid generating more than one world of that maximal quality. In other words, the objection, like Adams’ objection, conflates logically possible worlds with the (real) possible worlds produced by God. If one distinguishes logical possibles from real possibles and accepts a voluntarist conception of (real) possible worlds, as I have argued Leibniz does, the viability of the objection diminishes considerably. For the only reason God would find himself in such a conundrum is if he places himself in that conundrum.

However, for the sake of argument, let’s imagine that God does, in fact, place himself in such a conundrum. He got carried away, as it were, while generating possible worlds and generated several maximally good worlds — say, 50 best worlds. Would the theory of the best cease to function? I don’t think so.

I see two possible solutions. Both solutions presume the same starting point: God could actualize all 50 worlds simultaneously. Now, one version of this conclusion is a tacit critique of the way in which many use the word “world.” For Leibniz, world (monde) is synonymous with “creation” (e.g., G 6:107). Hence, if 50 parallel worlds co-existed, then these 50 worlds would be “the world.” Admittedly, there would need for some connection between them. More specifically, there would need to be some harmony between monadic perceptions across these overlapping worlds in order to say the monads occupy one world. — A monad with no shared perceptions occupies a world all its own, according to Leibniz.5 — But let’s imagine that there is some connection between these 50 worlds, such as a set of interdimensional bridges. By actualizing all 50 worlds with an interdimensional tether, God would successfully bring about a best of all possible worlds, one comprised of the 50 optimal worlds.

Alternatively, one could deny that God can tether these 50 worlds together. Working with a more traditional reading of the monadology, one could argue, for example, that none of the monads are capable of perceiving the others, since they are all part of discrete worlds. So be it. In this case, perhaps God could actualize all 50 worlds, fully independent of one another. Or framed as a question, Why must God create only one world? Whether Leibniz would approve of this solution, I am unsure. He certainly seems to wish for God to produce only one world. But I do not see any reason to think the scenario is impossible. And were it the case that God could face multiple best worlds, then there would be a rational basis for creating more than one world: All 50 worlds were equally good and superior to all competitors.

Now, again, I am inclined to think the proposed scenario is implausible. Because Leibniz distinguishes between logical possibles and real possibles, and because I read him as advocating a voluntarist theory of possible worlds, I find it implausible that God would generate multiple worlds of equal quality. Nonetheless, even granting the scenario, I do not think it succeeds in undermining optimism.

Before moving on, allow me one further note on the implausibility of this scenario. Notice that the objection does not, in fact, demonstrate that there are multiple possible worlds of equal quality. The objection simply presumes that, given enough worlds, this outcome is likely. However, I find the case dubious.

When truly considering the number of variables in a given world, the quantity staggers the mind. Since Leibniz takes an ontological approach to the optimal, let’s do the same. Each cell in the human body makes an ontological contribution to the quantity of being in the world. The human body contains approximately 37 trillion cells. That number, at this one moment in time, would need to be multiplied across roughly 8 billion people. But multiplied across history, that number would be by 117 billion people. That staggering number is merely an account of the number of animal cells in the human species to date. If we continue such accounting in protons, electrons, subatomic particles, and so on, the numbers defy imagination. The expanse only grows if we entertain Leibniz’s philosophy of organism or his monadology. And such an accounting is of only the ontological components of the world. Leibniz, of course, includes the realm of values in his accounting as well — the moral goodness of every thought, word, and deed, as well as the complex wholes of which they are part. The unimaginable breadth and depth that results is so staggering that I find it wildly implausible that any two worlds could possibly arrive at an identical accounting, no matter how many possible worlds there are.

One further point along these lines. The objection, once again, presumes logically possible worlds. Hence, variations in worlds can be negligible. For example, PW1 is identical to PW2 save one micro adjustment in position to one particle that has no effect on the whole. And such micro differences between worlds makes it seem quite plausible that several worlds could be very much alike and perhaps even of identical quality. However, I made the case in the previous chapter that such micro differences do not function in Leibniz’s way of thinking. When considering the fact that a possible world plays out only once in the realm of the possibles, I asked whether God might simply “tweak” that world in order to give it a second go. Using our world as my example, I suggested that God tweak a small property within our world system, such as a minor adjustment to Adam’s height. The suggestion, however, brought to light a flaw in this type of thinking. Leibniz takes it to be a hypothetical necessity that God does all things in the best possible way. To “tweak” PW1 is to perform something other than the best, which is impossible for God. Hence, to produce an alternative world, the change must be substantial enough to constitute a new world system, a change that demands that God do something different. And as also pointed out, given the interlocking nature of a cosmos, argued in the doctrine of concomitance, one substantial change is likely to cascade throughout the entire world system. In other words, micro adjustments of the kind logically possible worlds presume do not apply to (real) possible worlds, as conceived by Leibniz. And this fact — that any change must be a substantial change to the whole — makes it all the more implausible that the total accounting of two possible worlds might ever be identical.

One final point on this line of objection. As noted above, the objection does not demonstrate that two possible worlds can be of equal quality; it merely presumes this is likely, given the quantity of possible worlds. Leibniz could easily reply by building on a more sure premise, namely, “Our world exists.” In other words, Leibniz is convinced that if true equilibrium were to take hold, such that there really was no variation in quality between two worlds, no choice could follow (e.g., G 6:107). From this, he could reject his critic’s “likely” outcome as an unrealized possibility, evident from the existence of our world. For example:

If no best can be found amongst possible worlds, then no world would exist.

Our world exists.

Therefore, a best can be found amongst possible worlds. (1 & 2)

I have no doubt Leibniz’s critics would take issue with premise 1, evident from their efforts to find a procedure by which God could rationally choose from amongst equally good options. But without a demonstration that two possible worlds do in fact attain equal quality, Leibniz can dismiss the hypothetical as evidently false, given the existence of our world.

Now, there is one further objection to the theory of the best. This objection does not take aim at the idea of the best per se but at God’s duty thereto. The objection comes, once again, from Adams. He argues that the theory of the best implies that God has some obligation to possible worlds. In other words, some worlds are more deserving of existence than others. So it would be unjust of God to pass over the greater for the lesser. But Adams takes issue with the point on two fronts. First, he makes the obvious point that there is a fundamental difference between possible beings and actual beings, namely, the latter are real while the former are not. God has no obligations to the former, argues Adams, only to the latter.6 The notion that God has a duty to the best world over lesser worlds, then, trades on the very strange (and very flawed) idea that these possible worlds are somehow real, being owed something by God. But they are not. So God has no duty to any of them — not even to “the best.”