Greetings subscribers. As promised in my previous post, today marks the first of a trio of theological letters.

A dear friend, Raleigh, who works in the field of counseling-psychology asked me to consult on a book project. The work looks at Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in the light of Christian theology. Because Raleigh has grown increasingly sympathetic to Eastern Orthodoxy over the years, he asked me to help him better understand anthropology, deification, and asceticism in the Eastern Church fathers. The request prompted me to write three letters on these topics, which I will be publishing here in the coming weeks. Today’s installment looks at the basics of Eastern patristic anthropology.

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

Dear Raleigh,

Forgive me for writing a letter rather than a book excerpt. I know what you require is the latter, but my suspicion is the former is more likely to deliver what you need — an accessible summary of those distinctives of anthropology found in the Christian East. My hope is that the end result is of such a kind that it might be easily grafted into your book. If, however, my suspicions are incorrect, do not hesitate to say so, and I’ll take a more formal approach.

When considering how best to orient a reader to the anthropology of the Eastern Church fathers, several features of their thought come to mind, each one indispensable, and when taken together provide a fully orbed vision of man, his place in the cosmos, the effects of his Fall, and his road to restoration and healing.

The first is the notion that man is a microcosm of all that God has made. Common enough in the ancient world is the observation that reality consists of two types of things, things mortal and things immortal. That is to say, we discover in creation beings who are conceived, develop from seedling to maturity, only to age and die. Such is the plight of every organism. And yet, reality consists of more than just organisms. Truths of mathematics are somehow real but undergo no such change, and celestial beings — be they called gods or angels — were thought to be of such a kind — ageless, immune to the throes of time, and in some sense immortal.1

The divide appears in pagan writers, such as Plato,2 but is also recognized by the Hebrews. In the Book of Genesis, the division echoes in its talk of the heavens and the earth.3 The earth is the realm of mortals. From it springs forth plants and animals of every kind, and to the earth they return in the sleep of death.4 In the heavens, however, there is no talk of dissolution or death, only the creation and placement of celestial bodies, beings thought to be immortal by ancient man, and in whose ranks were the angelic hosts.5

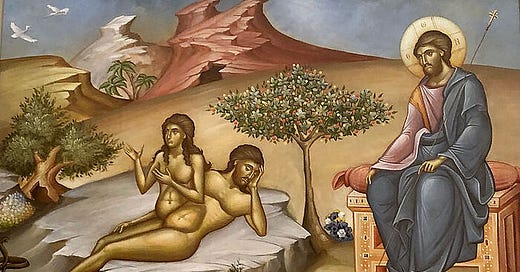

Yet, once the cosmos is set in order, God adds to his handiwork a peculiar creature, man — one taken from the dust of the earth but breathed into from heaven, making him a living spirit.6 What the Eastern Church fathers see in this imagery is the merger of all that God has made, things of heaven and things of earth, things mortal and things immortal. In a word, man is a microcosm of creation.7

But this union naturally raised a question in the minds of many ancient writers: Being a union of the heavens and the earth, was man created mortal or immortal? We find this question amongst the Alexandrian Jews in Philo, and it echoes in the Eastern fathers — as does the Alexandrian answer.8 Man was made neither, so the reply goes. Rather, he was created potentially mortal and potentially immortal. And this potentiality highlights yet another uniqueness of man — free will, or self-determination, to use the more ancient term.9 Unlike the irrational parts of creation, which simply act in accord with their nature, man has the exceedingly strange capacity to discern the order of nature and choose whether to adhere to it or not. In the case of Adam, this choice was between the earthly and the heavenly. His will functioned like the fulcrum of a balance scale, allowing him to choose for himself whether to raise up his lower nature to God, partaking of divine Life, or to drag down his higher nature and subjugate it to the life of mortal beasts. C. S. Lewis captures the point with a distinction between the biological life of animals, bios (βίος), and the life found in God, zoē (ζωή). Though the former is native to us, we are called to partake of the latter — of the Eternal Life of God.10

The choice sheds light on yet another aspect of the story. Well-known is the Hebrew teaching that man is an image of God. What is less known is a peculiar nuance that the Eastern fathers think to be of great importance. When the Holy Trinity determines to create man, God says, “Let us make man according to our image and according to our likeness.”11 Yet, when describing his craftsmanship, the text says God created man in his own image — no mention of likeness.12 The Eastern Church fathers believe the omission tells us something very important about the nature of man.13

These early Christians understand the image of God to refer to our spiritual nature — that we have reason, free will, and a mind capable of communion with the God whom we image.14 This image can never be erased, having been woven into the fabric of our nature. But we bear that image for a purpose: That we might actively imitate God, and in imitating him, come to bear his attributes in our person — attributes of love, virtue, and even immortality. To bear such attributes, or “energies,” to use the more ancient term,15 is what it means for man to bear the likeness of God, the image-bearer actively partaking of the Life of God by imitation.

This distinction between image and likeness brings to light something extraordinarily profound but easily missed: Man must participate in his own making. Though God determines to create man in his own image and likeness, the latter cannot be brought about without cooperation — without us choosing communion with and imitation of God. Such is the test of Eden and the call to Adam: Choose life.16

Yet, we know the story. Regrettably, Adam chooses to turn away from his Maker, bringing death upon himself and his progeny. Now, just as life can mean several things, so death can as well, and each meaning is integral to how the Eastern fathers understand Fallen man. The most obvious meaning is that the body ceases to live because the soul departs. Biological death of this kind is a natural consequence of Adam’s choice. Having turned away from the Fount of Immortality, he chose the life of mortal beasts.17 So, like the beasts, he and his progeny are destined to return to the earth from whence we came.

Yet, there is another meaning of death, namely, corruption — an unnatural or twisted state. Although animal death is a natural consequence of man’s retreat from God, it is unnatural that we die in this way. For we bear the image of God that we might raise up our mortal flesh to partake of Eternal Life.18 Having chosen death, however, the relationship between spirit and flesh is inverted, like a rider who has lost control of the beast he is meant to steer.19 So, we find ourselves in an unnatural state, our spirit subjugated to beastly passions.20 As St. Paul so aptly describes it,21 we know what we ought to do, but we fail to do it, our flesh having unnatural sway over our spirit, like a tyrannical taskmaster.22 Yet, our spirit retains its memory of what it ought to be, longing for more but incapable of attaining it. Such is the condition of Fallen man.

Now, there is one further meaning of death that offers a clue to how the Eastern fathers understand the road to restoration. That meaning is decomposition or decay. On the hand, the biblical text treats death as an enemy to be defeated — an unyielding tyrant who holds men captive.23 On the other hand, the Eastern fathers see it as a mercy. And here, death as decomposition is key.

When describing the corruption that has come upon us, Gregory of Nyssa uses the analogy of a pot.24 He imagines a potter setting out to craft a vessel made of two types of substance — analogous to the spirit and the flesh. If, in the process, these two substances mingle in a way contrary to the craftsman’s intent, then what is he to do, Gregory asks? Should he fire the vessel? Certainly not, since doing so would make the imperfection permanent. Instead, he must separate the two materials and begin again.

This analogy illustrates what the Eastern fathers see in God’s choice to return man to dust. By sentencing the body to dissolution, God separates soul from body, unmaking his creature. But this unmaking has a purpose: That he might be remade anew in the resurrection, undoing the corruption of the Fall.25 And this is how the Eastern Church fathers understand both the work of Christ and the Christian life of becoming a little Christ, conformed to his image.

The redemption of man involves both unmaking what has gone wrong and remaking us anew. The Incarnation, as understood by the Eastern Church fathers, serves this very purpose. The Son of God, who bears in his person divine Life, enters Fallen man in order to reunite him with the Eternal Life of God and heal what has gone wrong in our nature. His life, death, and resurrection is meant to set our nature right and raise it up to God. So, in the resurrection, we behold, for the first time, man as he was created to be: Transfigured and fully alive with the Eternal Life of God.26

The call to salvation, then, is a call to participate in this remaking of man.27 By turning back to God in repentance, embracing the faith of Christ, and entering the hospital of the Church, one participates in this remaking. The bridge between us and the Life of God that was torn down in the Fall is restored in our union with Christ through the divine mysteries — being buried and raised with him in baptism,28 receiving the Holy Spirit in chrismation,29 and partaking of Christ’s life-giving flesh and blood in the eucharist.30 And from this place of reunion begins the process of healing — the daily practice of turning and returning to God, the subjugation of the passions through fasting, the lifting up of the spirit to God in continual prayer. The life of the Christian is that of a little Christ, gestating in the womb of the Church, in the hope that through his daily imitation of Christ, he, too, might be remade and birthed alive, attaining the resurrection from the dead.31

In my next letter, I’ll speak at greater length about this hope and what is sometimes called deification, as well as the practices of the spiritual life, advocated by the Eastern Church fathers. But for now, I hope this helps.

Sincerely,

Dr. Jacobs

—

Nathan A. Jacobs, Ph.D.

Scholar in Residence of Philosophy and Religion in the Religion in the Arts and Contemporary Culture Program (RACC)

Vanderbilt University, Divinity School

http://nathanajacobs.com

https://vanderbilt.academia.edu/NathanAJacobs

Amongst Christian writers, the angels were thought to be “relatively immortal.” Recognizing that Saint Paul says “God alone is immortal” (1 Tim 6:16), they understood all creaturely immortality — be it the life of angels or eternal life through Christ — to be a participation in God’s immortality (see, e.g., John of Damascus, Expositio fidei orthodoxae, 2.3 (PG 94.868b). But no creature is innately immortal in the way God is. All come to be. All exist at his will. All could cease, if God willed it. See Justin Martyr, Dialogus cum Tryphone Judaeo, 5 (PG 6.488b); Irenaeus, Adversus haereses, 2.34.2 (PG 7.835b-36a); Methodius of Olympus, De resurrectione, 1.11 (PG 18.280c); John Chrysostom, Homiliae XXI de statius ad populum Antiochenum habitae, XI.4 (PG 49.124-6). See also Nathan A. Jacobs, “On Whether the Soul is Immortal According to the Eastern Church Fathers,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly (forthcoming), §§1-2.

Plato refers to the realm of change as the realm of “becoming.” The realm of stable realities, like mathematics, that are immune to change — the world of Forms, as he calls them — is the realm of “being.” The labels are meant to capture the contrast between stasis and flux. See Plato, Timaeus, 27d-28a.

Genesis 1:1

Genesis 1:11-12, 24-25; 2:7; 3:19, 23.

Genesis 1:14-17. Modern readers often notice the absence of the angels in the Genesis account. But in the ancient world, celestial bodies were often associated with the gods or heavenly hosts. See, e.g., Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2015), 3, 10, 25.

The language of spirit is notable because it indicates intelligence. The distinction between soul (ψυχή) and spirit (πνεῦμα) is that the former indicates the life of a body. Hence, ancient writers, including the Eastern fathers, understood all living bodies to have a soul, the life force that animates a body. Both animals and plants were thus understood to be ensouled (e.g., John of Damascus, Expositio fidei orthodoxae, 2.12 [PG 94.928b-c]; De haeresibus, 90 [PG 94.758b]). But spirit is used in reference to intelligent, bodiless powers, such as angels, as well as God. Neither is ever said to be a soul. The confusion emerges when man enters the picture because we find talk of both soul and spirit. The Eastern patristic understanding is that man has a soul because he is an animal. Yet, the soul of man bears intelligence. Hence, his soul is also referred to as a spirit. But the Eastern fathers did not understand these to be two distinct things, soul and spirit; rather, the spirit is the purest or most godlike part of man’s soul. See, e.g., John of Damascus, Expositio fidei orthodoxae, 2.12 (PG 94.924d-8b); and Jacobs, “On Whether the Soul is Immortal,“ n. 35.

E.g., Basil of Caesarea, De Spiritu Sancto, 9.23 (PG 32:109b-c); Gregory of Nyssa, De beatitudinibus (PG 44.1272bc); Catechetica magna, 6 (PG 45:25d-28a); Gregory of Nazianzus, Orationaes, 2.17; Maximus the Confessor, Ambiguum, 7.1 (PG 91.1077a-b); Cyril of Alexandria, Commentarium in evangelium Joannis, 10, v.14:21 (PG 74.284a-5c).

Cf. Philo of Alexandria, De opificio mundi, 135 with Nemesius of Emesa, De natura hominis, I.6.5-2, who echoes the view, making tacit reference to Philo. See also Theophilus of Antioch, Libri tres ad Autolycum, 2.27 (PG 6.1093b-6a); Methodius of Olympus, De resurrectione, 1.12-3 (PG 18.281d-84b); and Cyril of Alexandria, Commentarium in evangelium Joannis, I.9, v.1:14 (PG 73.160a-b).

The term autexousion (αὐτεξούσιον) literally means from one’s own substance or perhaps self-substancing. Ancient writers often spoke of free will as “the things that rely on us” (see, e.g., Apuleius, De Deo Socratis, 3.123-24, in pagan philosophy, or Nemesius of Emesa, De Natura Hominis, 28 (PG 40:749b) for a Christian source). The contrast was between the things of creation that are simply determined by God to do what they do and free beings who have a capacity to discern what they ought to do and choose to do it or not. Though divine freedom never carries the possibility of evil or corruption, the Eastern fathers, nonetheless, see free will as part of the image of God. See, e.g., Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, 7.7 (PG 9.458c-460a); Irenaeus, Adversus haereses, 4.4.3, 37.4, 38.4 (PG 7:982b-3b, 1101c-2b, 1108d-9c); Gregory of Nyssa, Oratio catechetica magna, 5 (PG 45.20d-25a).

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (Samizdat, 2014), 96-8.

Genesis 1:26 LXX.

Genesis 1:27.

For examples of the image-likeness distinction in the Eastern fathers, see Irenaeus, Adversus haereses, 5.6.1; and Basil of Caesarea, Homilia I: De Origine Hominis, 16. In keeping with this understanding of Adam, Tatian suggests that God did not make man good but with the free capacity to become good (Oratio ad Graecos, 7), and Theophilus of Antioch envisions Adam and Eve as children, placed in Eden so that they might mature and partake of divine immortality (Ad Autolycum, 2.24-25).

The term for “mind” (νοῦς) is one we will discuss more in the context of the spiritual practices of the Church fathers. I here differentiate it from reason and free will because Western scholasticism and Modern philosophy tend to reduce the mind to analysis and choice. But the Eastern Church fathers understand the mind to be far more than just these powers. And this more is what enables us to not merely know about God but to know God in the sense of intimate communion.

The term “energy” (ἐνέργειαι) is an important one in both the New Testament and in the Eastern Church fathers, and we will discuss it at greater length in the context of the proper end of man. For now, let it suffice that the term means more than just an outward act, having substantive connotations that are communicable, akin to the way the heat and light of fire can be communicated to iron. The definitive work on this term and its use in Eastern Christian thought is David Bradshaw, Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Basil of Caesarea uses the language of test in reference to the tree, which occasions Adam’s choice. See Basil of Caesarea, Homilia quod Deus non est auctor malorum, 9 (PG 31.348b-52b).

Basil of Caesarea, Homilia quod Deus non est auctor malorum, 8-10 (PG 31.345c-53a).

Athanasius, De Incarnatione, 3; Basil of Caesarea, De Spiritu Sancto, 9.23 (PG 32:109b-c); Gregory of Nyssa, De beatitudinibus (PG 44.1272bc); Catechetica magna, 6 (PG 45:25d-28a); Gregory of Nazianzus, Orationaes, 2.17; Maximus the Confessor, Ambiguum, 7.1 (PG 91.1077a-b); and Cyril of Alexandria, Commentarium in evangelium Joannis, 10, v.14:21 (PG 74.284a-5c).

I am here alluding to an analogy from Plato, where a chariot rider (representative of the rational nature) must learn to manage the spirited part of the soul and the passions. See Plato, Phaedrus, 246a-254e. Gregory of Nyssa echoes this analogy in De Anima et Resurrectione (PG 46.49b-52b).

Sts. Paul and James both identify the passions (πάθη) as the root of sin (e.g., Rom 7:14-25; Gal 5:16-17; Eph 2:3; James 1:14-15), and the point echoes in the Eastern Church fathers. The passions, simply defined, are reflexive (or pre-volitional) responses to perceived goods or evils. When smelling something enticing, our flesh inclines toward it with desire. When perceiving a danger, our flesh recoils from a desire for self-preservation. See, e.g., John of Damascus, De fide orthodoxa, 2.22 (PG 94:939c-49a).

Romans 7:14-25.

St. Paul famously describes this struggle in the seventh chapter of his letter to the Romans. The translations of the passage, however, are often misleading, sometimes capitalizing “spirit,” leading readers to believe Paul is describing a struggle between the Holy Spirit and the so-called “sin nature” — another unfortunate term that sometimes appears in translations. But in fact, Paul is describing the struggle between the fleshly animal nature and the rational nature — or, to use the language employed above, between the higher and lower natures. The point is evident because he uses spirit (πνεῦμα) interchangeably with mind (νοῦς) in Romans 7:27. As for what the spirit struggles against, his language is simply flesh (σάρξ), referring to the animal or fleshy body.

The New Testament refers to death as an enemy to be defeated (1 Cor 15:25-6) and also anthropomorphizes it in Revelation as one of the Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Rev 6:7-8). Hades, likewise, is sometimes depicted as a subterranean region, where the dead are held until the Day of Judgment (Lk 16:19-31), but it, too, is anthropomorphized as a sentient being. In the book of Revelation, Hades offers up its dead, employing an active verb (Rev 20:11-13). In early Christian literature, like the Gospel of Nichodemus, Hades is a figure who converses with Satan and who holds dead men within his belly (Gospel of Nicodemus, II.3 [XIX]). In early Christian iconography, Hades is depicted as a monstrous beast. And in John Chrysostom’s famous Paschal (Easter) homily, he speaks about Hades being vexed after taking into itself a man and encountering God (John Chrysostom, Homilia in Sanctam Pascham [PG 59.721-24]).

Gregory of Nyssa, Catechetica magna, 8. (PG 45:36a-b). The same analogy appears in Gregory’s brother, Basil. See Basil of Caesarea, Homilia quod Deus non est auctor malorum, 7 (PG 31.345b).

See, e.g., Cyril of Alexandria, Commentarium in evangelium Joannis, I.9, v.1:14 (PG 73.160a-b); and Methodius of Olympus, De resurrectione, 1.12-3 (PG 18.281d-84b). See also Jacobs, “On Whether the Soul is Immortal,“ §4.

Irenaeus, Fragmenta, 28 (PG 7.1244c); Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus, 3.1.1 (PG 8.856c-d); Athanasius of Alexandria, De Incarnatione, 20 (PG 25.129c-d); Epistola ad Adelphium episcopum et confessorem, contra Arianos, 4 (PG 26.1076c-7b); Cyril of Alexandria, Commentarium in evangelium Joannis, I.9, v.1:14 (PG 73.160c); Maximus the Confessor, Ad Thalassium, 42 (PG 90:405b-9a).

It has rightly been said that the Eastern fathers see salvation as primarily therapeutic, a process of healing man. See, e.g., C. Yannaras, The Freedom of Morality, trans. E. Briere (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1984), 143-8.

Romans 6:3-5; Colossians 2:12.

1 John 2:20, 27.

John 6:53-56.

Well-known is that Christian means little Christ, but less well known is the metaphor to which I here allude. The early Church would sometime allegorize the Church as Mary, gestating in her womb little Christs, and building on this metaphor, the day of martyrdom was one’s birthday, where he exits the womb and enters life, while apostates were stillborns, exiting the womb dead.