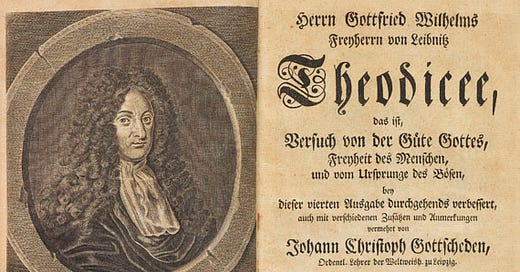

Renown rationalist G. W. Leibniz (in)famously answered the problem of evil by insisting that our world is the best of all possible worlds. I’ve just finished my book on Leibniz’s “optimism” for Cambridge University Press. As shocking as his claim is, my book argues that Leibniz’s reasoning is virtually impossible for classical theists to avoid.

I’m offering my readers something rather unconventional: a preview of the volume. I have posted every chapter here. All subscribers have access to a preview, and paid subscribers can see the full manuscript.

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work!

Chapter 1

Sufficient Reason and the Best Possible World

No fact can hold or be real, and no proposition can be true, unless there is a sufficient reason why it is so and not otherwise.

— G. W. Leibniz (E 707)

When teaching on the argument from contingency, I invite my students into a thought experiment. Let’s pretend that I’ve assigned an excerpt from Aristotle, but you don’t own the book. I put you on the spot and ask, How are you going to do the reading? You promptly point to Jane, answering that you’ll borrow her copy — question averted. Jane’s eyes shift awkwardly as she admits that she doesn’t own the book either, but she quickly looks to William, insisting that she’ll borrow his copy. William clears his throat, fessing up that he didn’t buy the book either. This goes on until we’ve cycled through every student in the class and arrived back at you. Will this infinite chain of borrowing yield a book? Obviously not. Only if someone in the class has the book to lend will the borrowers obtain a copy. And so it is with the argument from contingency.

Every being in our cosmos is contingent, depending on other things for existence. Not only do I depend on oxygen, food, and water, but my initial existence depends on my parents. But my parents, too, are contingent, depending on their parents. And so it goes down the chain. Our world is nothing more than an aggregate of contingent beings, each borrowing existence from something else. Like our book borrowing, existence borrowing can only yield existence if something in the chain has existence to lend, if something exists in itself. This “something” all men call God.1

The argument from contingency is exceedingly ancient with advocates amongst pagans, Jews, Christians, and Muslims.2 Something quite similar is afoot in Leibniz’s theory of the best. The stage is set for his case by a burgeoning dispute between rationalists and empiricists in the so-called “Age of Reason.”

The Principle of Sufficient Reason

Empiricism was on the rise in Leibniz’s day, as many sought to dispel the dreams of scholastic metaphysicians and turn instead to hard facts, the sorts of facts that can be detected and proved by the senses.3 Rationalism, by contrast, looked to analytic truths, which can be demonstrated by an examination of terms, the sorts of truths that populate math and geometry. More technically, the empiricists emphasized a posteriori truths while the rationalists emphasized a priori truths. The former are truths that follow from experience while the latter can be deduced apart from experience.

To illustrate, consider how many people are in my kitchen (or yours) right now. Nothing about the terms people or kitchen or my (or yours) tells us the answer, and whatever answer is true now may not be true five minutes from now. The answer requires investigation. We need to look. This is an a posteriori truth, one that follows from experience. By contrast, consider how many sides a square has. We need not look at any particular square to answer. If you know what is meant by the term square, then you know it has four sides. This truth is a priori, known apart from experience.

Now, Leibniz notices something rather important about a posteriori truths. Consider why they follow from experience: If there are in fact two people in my kitchen, nothing about these terms (two, people, my, kitchen) requires that they are paired this way, and whatever pairing happens to be true could be otherwise. In other words, a posteriori truths are contingent. Their being so depends on other facts, and without these facts, they would not be so. But the same cannot be said of analytic truths. To negate four-sided of square is to land in contradiction. It cannot be otherwise. The pairing is necessary.

The observation is noteworthy when considering Leibniz’s Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR). The principle is straightforward: “No fact can hold or be real, and no proposition can be true, unless there is a sufficient reason why it is so and not otherwise” (E 707; also E 716; C 25-6; G 6:127; 7:301). In other words, if something is true, there is a reason it’s true, a reason sufficient to make it so. Think of it this way. We hear an explosion in the adjacent room and investigate. When asking what caused it, the offered explanation is: The room was filled with oxygen. Surely this is part of the reason. Oxygen plays a role in combustion. But this is not a sufficient reason. I presently sit in an oxygen-rich room that is combustion free. More is required to explain the explosion, and presumably, there is more; presumably, there is a sufficient reason. Things don’t just happen.

Bringing these insights together, Leibniz notices a stunning fact about a posteriori truths: They fail to satisfy PSR. Every historical fact, every event in our world involves a pairing of terms that could be otherwise. — I’m sitting in front of my computer. You’re reading this book. Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 B.C. — There is no necessity in how these terms are paired. The event described could be otherwise without contradiction. And so, the event is contingent. As such, its reason for being so is not found in the facts of the event but in something prior that gives rise to those facts.4 But if this “something prior” is also a historical event (e.g., I am sitting in front of my computer because I chose to work today), we run into the same problem: This prior event (I chose to work today) also involves a pairing of terms that could be otherwise. So this event, too, is contingent, also requiring something prior. Just as our book borrowing cannot regress infinitely, so our search for a sufficient reason cannot regress infinitely.5 What, then, is needed to end the regress and yield a sufficient reason?

The answer is strange: What is needed is an existential analytic truth. In other words, we need a necessary truth that is as analytic as “a square has four sides,” one where the paired terms cannot be negated without contradiction. But the analytic truth must concern a fact of existence. This demand is exceedingly odd. For most analytic truths, such as bachelors are unmarried men, concern abstract definitions, not facts about existence or existing beings. But PSR demands an analytic truth about a fact of existence.

PSR, God, and the Best

As odd as this demand is, there is an argument that once claimed to offer an existential analytic truth, namely, the ontological argument. The truth it offered is: God exists. Those familiar with Anselm’s argument know that the ontological argument, in short, claims that if one understands what God is (a priori), then he also understands that God exists. In other words, the argument makes the case that the pairing of exists and God is as analytic as the pairing of four-sided and square. And so, the statement “God does not exist” is a formal contradiction on par with “a square does not have four sides.”6 Leibniz agrees (e.g., G 4:405-406; E 373-377). While he believes that Anselm’s formulation of the argument has deficiencies, Leibniz also believes the deficiencies are fixable. So, in the end, Leibniz accepts that there is indeed one existential analytic truth: God exists.7

Very well. Have we, then, arrived at the sufficient reason for historical events and other a posteriori truths? Not quite. Having arrived at an analytic existential truth, we have stopped the regress of contingent truths. But the existence of God is still only a partial reason for our chain of contingencies. We still need a reason why this chain of events rather than a different chain? And Leibniz believes he knows why. According to Leibniz, there is one further analytic truth about God that is extremely important: God always wills the best (G 6:49-50, 106-7, 127-8; 7:309-10; C 21). If we understand what God is, then we understand this principle. And the pairing of these two analytic truths about God — that he exists and wills the best — offers a sufficient reason for every a posteriori truth. Our world, its laws, its events, God’s providential deeds are all so because they are best. Or to quote Leibniz, “The true cause why certain things exist rather than others is to be derived from the free decrees of the divine will, the first of which is to will to do all things in the best possible way” (G 7:309-10). Only this answer can satisfy PSR.

But why is Leibniz convinced that God always does the best? How does this truth follow a priori from the idea of God? The answer requires a look at medieval faculty psychology (MFP), which sits in the background of Leibniz’s case (e.g., E 252). According to MFP, rational agents have a faculty of intellect and a faculty of will. The intellect is the judging faculty while the will is the choosing faculty that moves the agent into action. It was commonly accepted that all rational creatures desire happiness, and happiness is pursued by means of perceived goods. Our deliberations, therefore, are based on assessing the goods available to us and determining which are best.

When, for example, our body tells us we are hungry, we judge whether eating or not is the greater good. A monk may conclude that fasting is best because turning the soul toward God is a greater good than filling the stomach. A glutton may conclude that eating — and eating in excess — is best because the pleasure of food is the greatest good. And still another may land somewhere in between. Wherever one lands, a series of more specific judgments then follows. If one determines to eat, he must then judge what to eat, how to get it, how much, and so on. Each judgment and the chain they form is a reflection of what the agent thinks is best. Making such judgments about available goods is the job of the intellect.

The will, by contrast, is the acting faculty. We all know what it’s like to arrive at a judgment, such as I should exercise, and not do it. MFP recognizes that judgments do not necessarily translate into action. An act of will is required. Now, there is a medieval dispute about whether the will must follow the judgments of the intellect. We will return to this discussion in chapter 4, but for now, let it suffice that both sides agree that if the will acts, it acts on a judgment about the best.

So, what prevents a rational agent from doing the best? According to MFP, there are only two reasons. First, the person is corrupt, esteeming lower goods higher than he ought. Such bent desire can draw the will, or the intellect, or both away from higher goods. Second, he may rightly esteem a good — say, health — but be mistaken about how to get it. In short, the only reason a person might fail to do the best is corruption or ignorance. I trust the case for the best is quickly becoming clear.

Neither ignorance nor corruption is applicable to God. Omniscience entails that God knows all goods and which goods are best. God’s omnibenevolence and incorruptibility (two sides of the same coin) make it impossible that the divine intellect or will might be bent or clouded, declining away from the best for an inferior good. Hence, it follows from the divine attributes that God must know the best means to any given end and favor the best over all competitors (C 24). So, the hypothetical necessity follows: If God wills something, he wills it because it is best (G 6:123-4; 391-2).

Given that this is the conclusion for which Leibniz is best known and most often maligned, he is worth quoting at length:

God is the first reason of things: for such things as are bounded, as all that which we see and experience, are contingent and have nothing in them to render their existence necessary … Therefore one must seek the reason for the existence of the world, which is the whole assemblage of contingent things, and seek it in the substance which carries with it the reason for its existence, and which in consequence is necessary and eternal. Moreover, this cause must be intelligent: for this existing world being contingent and an infinity of other worlds being equally possible, … the cause of the world must needs have had regard or reference to all these possible worlds in order to fix upon one of them. This regard or relation of an existent substance to simple possibilities can be nothing other than the understanding which has the ideas of them, while to fix upon one of them can be nothing other than the act of the will which chooses. And this intelligent cause ought to be infinite in all ways, and absolutely perfect in power, in wisdom and in goodness, since it relates to all that which is possible…. Now this supreme wisdom, united to a goodness that is no less infinite, cannot but have chosen the best. For as a lesser evil is a kind of good, even so a lesser good is a kind of evil if it stands in the way of a greater good; and there would be something to correct in the actions of God if it were possible to do better. (G 6:106-7)

The analytic case runs something like this:

An omniscient intellect is that which cannot fail to know all goods including the best.

God’s intellect is an omniscient intellect.

Therefore, God’s intellect cannot fail to know all goods including the best. (1 & 2)

An incorruptible will is that which inclines toward every good proportionate to its goodness and thus toward the best above all other goods.

God’s will is an incorruptible will.

Therefore, God’s will inclines toward every good proportionate to its goodness and thus toward the best above all other goods. (4 & 5)

If God’s intellect cannot fail to know the best and God’s will inclines toward the best above all other goods, then if God chooses to create a world, the world he creates will be the best possible world.

God chose to create our world.

Therefore, our world is the best possible world. (3, 6, 7, & 8)

The case is valid,8 so it can only be refuted by taking issue with one of its premises. But for the classical theist, there is little to critique. We will consider the efforts to avoid this conclusion in chapter 6, but for now, notice that the case naturally raises the problem of evil.

Evil and the Best

The classical formulation of the problem is David Hume’s summary of Epicurus: “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Whence then is evil?”9 The problem attempts to show an incompatibility between the existence of evil, on the one hand, and the divine attributes of omnipotence and omnibenevolence (and tacitly the other omnis), on the other. Most philosophers of religion today grant that there is no formal contradiction in the problem, and so, the analytic problem of evil fails.10 Ironically, however, Leibniz’s case for the best nearly offers a valid formulation of the analytic problem of evil.

Keep in mind that, in MFP, neither the intellect nor the will choose evil as such. Evil is always chosen because of a good to which it attaches. Theft is chosen because of the good coveted, fornication for the good of sexual pleasure, masochism for the good of power, and so on. Evil is never done for evil’s sake. It can only spring from either ignorance or corruption, both of which distort otherwise good desires.11 If neither ignorance nor corruption applies to God, then God cannot will evil. But Leibniz has shown that every event in our world (every a posteriori truth) must be traced to God. Therefore, evil events should be impossible. How, then, can Leibniz explain the reality of evil?