A friend, “Zeffirelli,” asked my stance on the existence of fairies. He shared with me that a well-known author had recounted a personal encounter with one, which sparked online discussion on the topic. While I don’t have strong views on the matter, I did offer some general insights on my basic approach to such things. Note that I’ve added a postscript on some recent work of mine in film and art that, oddly enough, intersects with this topic. Please subscribe and support my work!

Dear “Zeffirelli,”

I had no idea that fairies were a hot topic! Such trends slip past folks like me who avoid social media. To your question, I admit that I do not have a firm position on the topic, so I can’t offer you that. However, I can offer more general thoughts on how I approach such matters.

Let’s begin with the two main questions. Is it possible that fairies exist? If so, do I believe they exist? My stance on the former question is firmer than my stance on the latter, so I’ll begin there. The word “impossible” is rather overused — and imprecisely so — when talking about matters such fairies and other possible beings. In literature, film, and real life, the skeptical sort will all too often say that the existence of this or that is impossible. What he really means is something closer to improbable, though his meaning hardly approaches even this. The colloquial “impossible” really only means that one is unaware of any evidence for the existence of such a thing; he personally finds said thing’s existence unbelievable; therefore, he balks at the very suggestion that it exists. Such an assessment hardly makes the object of discussion impossible. Nonetheless, the word “impossible” points us in the right direction. For it moves into the territory of modalities or modes of existence. And this, I think, is the right starting point.

When considering whether a thing exists, we are right to begin by asking what that “thing” is — that is, it’s proper definition — and whether the “thing” proposed is metaphysically possible. On this question, I find medieval modal logic to be rather useful. To grasp its approach to “the possible,” we must look at realism and what it tells us about the possible and the real.

By way of refresher, and to avoid any confusion, realism concerns the question of whether the commonalities identified by mind and applied to multiple things are real or whether they are mental fictions that the mind imposes on reality. For example, when I look at Paul, Timothy, and Silvanus, I identify a common nature or species or kind, namely, human. I identify a common genus, namely, animal. I identify common properties, such as bipedal or ten-fingered. Realism presumes that these general nouns identify something real outside of the mind that these several individuals somehow have or participate in or share. Human is not a mental fiction invented to group individuals that are in fact unrelated. Rather, the term identifies something that is real outside of the mind that these several individuals all have or participate in or share — hence, realism.1

Now, what precisely the thing is that the mind identifies is a point of contention amongst realists. Several theories exist. Some realists believe the referent is an archetype that exists independent of our material world. When encountering a geometric shape, for example, we identify its type — say, circle — and then assess whether it is a good or bad representation. This common practice compares the particular instance of the shape with something else, something distinct from the instance. We compare “this circle” to an archetype — to circularity as such. And this circle is good or bad based on how well it approximates that archetype. Plato referred to these ideal archetypes as “Forms,” and he theorized (so the standard reading of Plato goes) that there is an entire world of Forms after which our material world is modeled.2 Later Platonists — as well as many Jews and the Christians — modified the theory to suggest that the Forms, also called “Ideas” by Plato, are divine Ideas. We compare a particular circle to the Idea of circle in the mind of God. Still other brands of realism, such as that of Aristotle, suggest that forms are within material objects. Matter is a mere recipient of properties, like fabric that receives shape from the objects it drapes. The location of form is thus matter itself — the form being what gives matter structure. And still other brands of realism combine these theories, advocating both divine Ideas and the presence of form within matter.3

Regardless of where one locates the forms, the theory of form offers metaphysical substance to the distinction between the possible and the real. Let us grant, for a moment, that the archetypes to which we compare material objects are God’s Ideas. We encounter a material object, cycle through the divine Ideas,4 and find that the object conforms to the Idea human. Both the divine Idea and the material object are real. But the divine Idea is not concrete. The Idea itself is an abstract possibility; the material manifestation of that possibility makes the possible real. If, however, God had chosen to not create human persons, then we could still discuss in a metaphysically meaningful way the possibility of human beings, referring to the abstract possibility in the divine Mind that God could create, but we would also say of that possible that it does not exist. Alternatively, if we take Aristotle’s theory that form manifests within matter, we get the same result. In this case, the possibility refers to material potential. Matter has the potential to be any number of things — this being the sole trait of matter, according to Aristotle.5 One such thing is a human being. Were we in a world where human beings do not exist, then we could speak about the possibility of human beings, referring to the material potential of matter to manifest such a being, but we could also say that no such being is concretely real, since that material potential is not presently realized. Notice that within realism, “possible” has metaphysical weight to it. The term does not identify mere mental fancies or whims or wishes, nor is it mere semantic combinations. Possibles are metaphysically grounded, referring to the potential of matter to be something or to the power of God to create something or some combination thereof.

Existence, by contrast, refers to the concrete manifestations of such things. Like with form, the theories about where precisely existence is located varies amongst the realists. Some locate it in matter, others in some other principle that has both form and matter.6 But regardless of where one locates it, the result is the same for the topic at hand. Existence indicates the distinction between the mere possible and the concrete manifestation. In the immanent theory of form, if the potential for matter to be this or that moves into concrete reality, then this or that comes to exist. In a transcendent theory of form, if God chooses to make a concrete instance of this or that Idea, then this or that comes to exist. Such is the relationship between the possible and the real, between mere possibility and concrete existence.

Now, the relationship between the possible and the real brings us to medieval modal logic, which neatly organizes the relationship between possibility and actuality.7 Modal logic examines the various “modes of being,” namely, possible, impossible, and necessary — or, more precise, the impossible, possible-but-not-necessary, and possible-and-necessary. The first question is whether the “thing” posited is possible or impossible. The basic litmus test is contradiction. Do the predicates ascribed to the “thing” in question produce a formal contradiction or not?

Let’s take Human as our example. This term places before the mind a rational (specific difference) animal (genus), to use Aristotle’s method of defining a term. No formal contradiction appears in this subject-predicate combination. If we press the investigation further, looking at the various properties ascribed to the proposed being, we discover things like bipedal, two-armed, ten-fingered, two-eyed, and so on. Again, no formal contradiction emerges. So the being posited is modally possible.

We might contrast the above example with the subject-predicate combination not-four-sided square. Such a term places before the mind a formal contradiction. Essential to square is four-sided. Thus, the negation of this predicate lands us in contradiction. We cannot take the next step of assessing whether “it” exists because the “thing” proposed does not clear the bar of basic coherence. As such, the “thing” posited is modally impossible, existing neither in material potential nor in the divine Mind nor in reality but in words only. Or put otherwise, before we can assess whether something exists, we must first posit a thing. Incoherent word combinations fail this basic test. Such contradictions are nothing more than meaningless utterances. And as such, “they” are modally impossible. This is why medievals, such as Aquinas, say that contradictions stand outside the bounds of even omnipotence.8 Not even God can make “them” because “they” are nothing but nonsensical word salads.

Now, let us say that we have before us something that is modally possible. The next question is whether the possible thing exists “in the realm of the possibles” (i.e., amongst the Forms or in the Mind of God or in the potentialities of matter) only or in the world as a concrete reality. In the case of our first hypothetical, human, a look in the mirror demonstrates the conjunction of possibility and existence. Hence, this possible being exists in both the realm of the possible and in reality.

One further question, then, remains. Is this conjunction of possibility and existence a necessary or contingent conjunction? In other words, is existence conjoined with possibility here by necessity, such that it is impossible that human beings not exist, or is the conjunction contingent, such that it is possible for human beings to not exist? Another way of putting this is to ask whether negating “existence” in reference to “human being” lands you in a formal contradiction, similar to the way negating “four sided” of “square” lands you in contradiction? If existence can be negated of the possible being without contradiction, then that being is contingent. It is a possible being that happens to exist, but it is also possible for it to not exist. If, however, negating “existence” of the being yields contradiction, then it is a necessary being: It is impossible that the being not exist.

Anselm’s ontological argument is based on the claim that negating “existence” of “God” yields a formal contradiction. Hence, if one acknowledges that God is a possible being, then one must acknowledge that God necessarily exists. For a contingent being would not be worthy of the name “God”; hence, one must either say that God is impossible — that is, the very notion of God yields formal contradiction— or admit that God is possible and therefore exists.9 Such is the nature of necessity.

Contingency, by contrast, offers us a possible being that may or may not exist. In the case of a human being, we see in ourselves this possible being conjoined with concrete existence. However, we recognize that we have not always existed, and there was a time when human beings did not exist. At that time, the idea of a human being would be just that, a mere abstraction of a possible being that is not conjoined with existence. Hence, human beings seem to fall under the possible-but-not-necessary category. That is to say, our mode of being is contingent.

Now, at the risk of muddying the waters, I will add one further caveat on modalities. The above assessment of a human being does not necessarily demonstrate that human beings are in fact contingent. For it is possible for a human being to have necessity by distribution, even when it depends on something else for existence. To see the point, let us grant that God exists by necessity, and let’s also grant, for the sake of argument, that God does not have contrary choice regarding what he creates. Were this the case, then all that God makes would also exist by necessity. Yes, there would be a time before God created human beings, but the eventual creation of human beings would be inevitable, following necessarily from the existence of God. Hence, our existence, being conjoined with God’s existence, would be modally necessary as well. This is what is called the distribution axiom. If two things are conjoined of necessity and modal necessity applies to the one, it distributes to the other.10

With these metaphysics before us, I’ll start with the question of whether the existence of fairies is impossible. As a metaphysical question, an assertion of impossibility requires formal contradiction. I see no such contradiction in the concept. To oversimplify the history of fairy lore, the concept essentially posits a being that is humanoid, except for its extreme smallness and the addition of wings. Assuming I’m correct and no contradiction has slipped by me, then such a being is metaphysically possible. I suppose one could add to the concept the common trait of magical powers and from this claim impossibility. However, that would go to a further question on how one defines “magic” and whether this too is metaphysically impossible. I would not concede the latter. Yet, so as to simplify matters, let’s set to one side the nature and possibility of magic and instead ask whether such powers are an essential trait to qualify a being as a fairy. I do not think they are. If I were to encounter a being who fit the common description of a small humanoid with wings but learned she had no magic abilities, I would not hesitate to say I met a fairy; I would simply conclude that fairies do not have magical powers — or, at least, this one does not. I don’t see in this a contradiction of the kind that occurs should I say I found a square that has only three sides. Hence, the question of magic is immaterial to the topic. So, I’m left to conclude that fairies are indeed modally possible beings.

I suppose one could argue that fairies are modally possible in themselves, but there is some incompatibility between them and our world. This goes to the notion of compossibility, which was perhaps most significant in the thought of G. W. Leibniz. When discussing the problem of evil and possible worlds, Leibniz explores not only modal possibilities but the relationship between possibilities. We very often speak rather casually about what is possible. — Of course this or that is possible. — And this is especially true when speaking about what is possible for God. But we rarely consider the fact that our world is highly complex. Any possible that is introduced into it becomes part of a complex network of possibles. Incompossibility is the notion that there are some possibles that are incompatible.11 Let’s say that p is possible and q is also possible; this does not mean that a world with both p and q is possible. If, for whatever reason, p and q are mutually exclusive, then it follows that if p, then not-q, and if q, then not-p. In short, p and q are incompossible. To use a more concrete example, it may be possible for God to guarantee that the world he creates is void of moral evil. If, however, the existence of self-determining creatures entails the possibility of moral evil, as is typically argued in the free will defense, then this guarantee is incompossible with the existence of free beings. To create the latter is to negate the guarantee of the former and vice versa.12

Applied to possible beings, it’s entirely possible that there are possible beings who are incompossible. To create a world with being r is to negate the possibility of being s and vice versa. So one could argue that fairies are modally possible in themselves, but there is something about our world that is incompossible with their existence. Hence, our world, being the set of possibles that exists, negates the actualization of fairies. I know of no such argument, nor do I see anything in our world that might produce such an incompossibility. Nothing about our world seems to be incompatible with the existence of small, winged humanoids. Thus, I dare stick with my original conclusion that fairies are modally possible.

Granting this conclusion, the subsequent question is whether they reside in the realm of the possible only — be that in matter or the mind of God or amongst the Forms — or whether they have now or have ever had concrete existence. Two ways of exploring the question present themselves. The first is the a priori approach; the second is the a posteriori approach. I presume you’re familiar with these terms, but just to be sure, an a priori investigation does not rely upon experience. Mathematics, for example, deals in the abstract nature of numbers; it does not rely upon concrete instantiations of these numbers. Knowing how many people are presently in my living room, by contrast, requires empirical investigation, since there is nothing in the combined terms that offer insight into the answer. Admittedly, when it comes to existential truths, such as whether fairies exist, it’s not an unreasonable assumption to presume that a posteriori investigation is required. However, before I jump to that, I will say that there is an a priori avenue by which one might commit to such a belief. Here, distributive necessity is relevant.

Granting the modal necessity that God exists, which I do, we open the door to modal necessity by distribution. You’ll recall that when I explained distributive necessity above, I used the example of a human being. If God does not have free choice concerning creating human beings, then the eventual existence of human beings would follow from the existence of God, and thus the modal necessity of the latter would distribute to the former. The same goes for fairies. If there were reason to think that God, of necessity, creates fairies, then one could be committed to their existence on a priori grounds. So, are there any reasons to believe in such necessity? Believe it or not, there is one avenue by which one could advocate the distributive necessity of fairies.

The avenue I have in mind pairs two commitments. The first is what is sometimes called the “principle of plentitude.” The basic idea is that the cosmos is an expression of divine wisdom and power. The hierarchy of beings from rocks to plants to animals to humans, and so on, is an expression of the various dimensions of the divine nature. Much like the way a musical composition expresses the creativity of a composer, giving concrete articulation to his creativity, so the world gives concrete articulation to the divine nature. And just as the more pieces an artist produces, the clearer the articulation of his talents, so in the same way, the more varied and complex the world, the more clearly it expresses the divine nature. The principle of plentitude suggests that this, being the purpose of our cosmos, must represent a maximal representation of compossible beings.13

If the principle of plentitude is paired with a commitment to divine emanationism — a pairing that certainly appears in the ancient world — then we have distribution by necessity. What I mean is this. While those in a Judeo-Christian context tend to presume that God has free choice, freely choosing what to create and what not to create, this presumption was not a given in the ancient world. Many pagan philosophers held that God simply emanates the world involuntarily.14 On such a view, the world and everything in it is the inevitable byproduct of God.

Combining these two commitments, then, the existence of creatures is as necessary as the existence of God. For God does not choose to make creatures, and thus, no choice to not make creatures is possible. The world is just the overflow of the divine nature. Combined with the principle of plentitude, this overflow is an articulation of the divine nature that aims at maximizing the articulation of God. The result is the belief that whatever God can produce, he does in fact produce. If fairies are modally possible beings, then, and if they are compossible with the things of our world, then we can infer from the existence of God and the principle of plentitude that fairies necessarily exist. This did not necessarily mean that they exist in our world or on our planet or in our dimension. But these commitments would lead to an a priori commitment that fairies do exist somewhere in some form.

Now, for my part, while I think there is something true about the principle of plentitude — the world does in fact express the divine nature, articulating its various attributes — I deny divine emanationism. I won’t go through the case of the Eastern Church fathers for the view, but suffice it to say that I agree with them that God has free choice, and that this free choice includes what to create and what not to create. For this reason, I would also deny that modal necessity distributes to the things of our world. The world and its members are contingent. Such commitments, therefore, point me to a posteriori considerations instead when considering the existence of possible beings. That is to ask, is there any evidence that the fairies have concrete existence?

Before I consider the question of evidence, allow me to first offer an aside on belief. I mentioned that the colloquial use of “impossible” is often tied, not only with a lack of evidence, but also with a sense of implausibility. I have no doubt that, for many, the very idea that fairies might exist is prime facie absurd. And, indeed, there are often ideas or claims that strike us as so patently absurd that we can hardly entertain them. Yet, I think it is important that we proactively put in check such dispositions. William James points out that we have innate tendencies to find certain things plausible and implausible; some suggestions are naturally live options for us, while others are dead options. But, as James also points out, this intellectual disposition is not based on a rational assessment of the proposition. It reflects something of our idiosyncratic inclinations. The response is pre-rational.15

Sociologist Peter Berger has pointed out something similar in his book, A Rumor of Angels. He explains, “For better or worse, men are social beings. Their ‘sociality’ includes what they think, or believe they ‘know’ about the world. Most of what we ‘know’ we have taken on the authority of others, and it is only as others continue to confirm this ‘knowledge’ that it continues to be plausible to us.”16 As Berger explains, should one discover that his beliefs are contrary to what the majority “know” about the world, this prompts a crisis of belief: “At best, a minority viewpoint is forced to be defensive. At worst, it ceases to be plausible….”17 He uses the example of the belief that the stars determine our fate. Should someone from a far off country where the majority holds this view land on the shores of America and learn that the view is not widely held, if not deemed laughable, the person will face such a crisis of belief. They will be tempted to “go native” and abandon the belief for what the majority holds on the matter.18 But, Berger notes, perhaps your response is that they should abandon the belief since it is absurd. Yet, Berger replies, were the situation reversed and you were to land on their shores and find yourself in the minority in rejecting the fate-determining nature of stars, you would face the very same crisis of belief. And this is precisely what happens often with anthropologists who are often tempted to “go native” with the cultures they study.

Now, Berger’s point is simply this. Plausibility of belief is often socially conditioned. The assessment is not rational. It is animal. We as social animals have a tendency to embrace the majority position for survival reasons. The society itself, for this reason, tends to shape our innate dispositions — to shape the “live” and “dead” options that James discusses. My point is this. I have no doubt that many find belief in fairies a “dead” option. The idea simply seems too strange; the suggestion of such a thing is dead on arrival. Yet, as both James and Berger point out, this is a pre-rational response. The disposition is not based on rational assessment. And for this very reason, it is wise to admit the disposition but to place it in check in order to allow reason to have its say. We far too often are like Lucy’s siblings in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe who think it “impossible” that she slip through a doorway into another world, when we should be more like the Professor, who let’s reason have its say.

So, then, letting reason have its say, I admit that I have not made a full examination of the a posteriori — that is, the empirical — evidence for the existence of fairies. I am aware of reports or accounts of real fairies. I am also aware that some of these were exposed to be hoaxes. Perhaps the most famous such hoax is the account of Elsie Wright and her cousin Frances Griffiths. The two girls supposedly had encounters with fairies, and they had photographic evidence of the encounter. The account duped Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, best known as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, and the entire Theosophical Society. The girls later admitted to the photos being staged with paper cutouts, I believe it was. One of the girls insisted that while most of the photos were fakes, one was of a real fairy — a claim she maintained until her death. But admittedly, the report is tainted, given the admission of having duped the public. I really know very little about the other reports and accounts. I have never catalogued or investigated these, looking into authenticity, motives, and other such matters one might look into when scrutinizing such reports. Hence, I have little to say about the purported encounters with real fairies.

I admit, however, that when it comes to beings that appear across multiple cultures throughout the world and across time, I try to remain open-minded, despite modern and post-modern influences on my intellectual dispositions. Moreover, I tend to believe that our world is much older and more expansive than we tend to think. Inquiry always favor that the world is larger, never smaller. Frankly, I see nothing intellectually virtuous about skepticism. To again cite Lewis’ Narnia Chronicles, like the dwarves, one can be hellbent on not being fooled. This aim is easily accomplished. Risk belief in nothing, and you will never be fooled into believing something that is false. But you will also never discover anything that is true. Hence, in the end, I prefer open-minded agnosticism that is willing to risk believing something that may turn out to be false.

So, do I believe in fairies? I cannot say strongly that I do. I can only say what I have in fact said. I believe they are modally possible beings, who, if they have concrete existence, have it contingently, not necessarily. I am aware of reports and accounts of their existence, but I have never investigated the evidence thoroughly enough to say whether I believe it. But despite any cultural tendency to laugh at such a belief, I am willing to be persuaded, since I see nothing inherently problematic about the existence of such a being. Thus, I have an open-minded agnosticism that is willing to be persuaded, should the evidence commend such a belief.

I hope that helps.

Sincerely,

Dr. Jacobs

—

Nathan A. Jacobs, Ph.D.

Scholar in Residence of Philosophy and Religion in the Religion in the Arts and Contemporary Culture Program (RACC)

Vanderbilt University, Divinity School

http://nathanajacobs.com

https://vanderbilt.academia.edu/NathanAJacobs

POSTSCRIPT

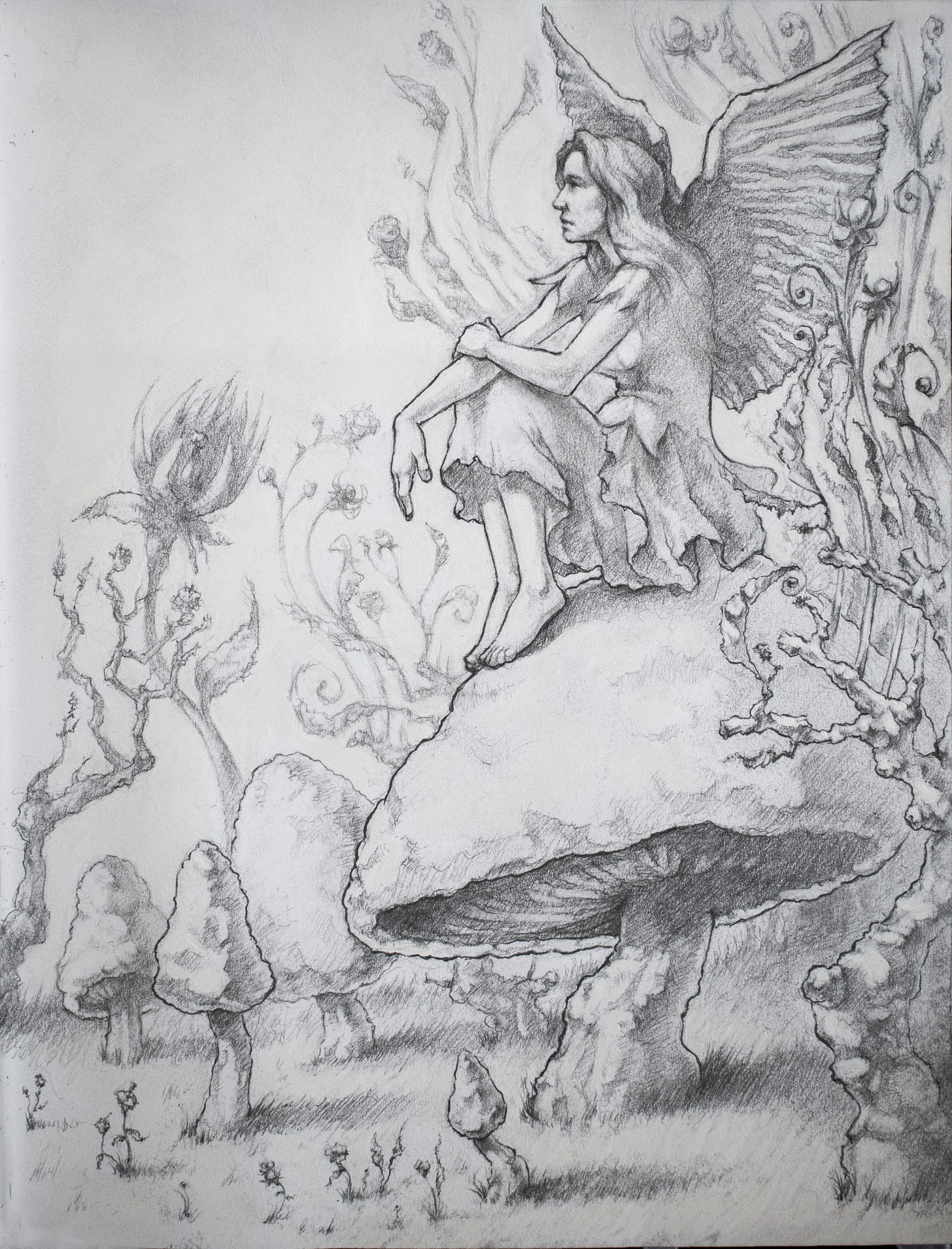

I’m currently in development on a streaming series that centers around fairy lore. I have been working on concept art for the project, which is what sparked the conversation about fairies. Below are a few samples. Enjoy!

For an overview of realism, see Frederick Copleston, “The Problem of Universals,” in History of Philosophy Vol. II Augustine-Scotus, 9 vols. (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1950), vol. 2, 136-55.

Plato’s theory of the Forms is most famously espoused in The Republic, 506d-21b. I identify problems with this standard reading in “The Metaphysical Idealism of the Eastern Church Fathers,” Rethinking Idealism and Immaterialism, eds. Joshua Farris and Benedikt Paul Gock (Routledge).

I discuss further the different forms of realism and systematically explain the model amongst the Eastern Church fathers, which I advocate, in “The Metaphysical Idealism of the Eastern Church Fathers.”

Why the mind knows the divine Ideas is also a matter of dispute amongst realists. Plato advocated that the soul is from the world of the forms and thus has memories of them. NeoPlatonists held that the soul is a divine spark, which is why it has within it the divine Ideas. Jews and Christians held that the soul is an image of the divine Mind, and this is why it knows the Ideas. Such a question, like the other disputes amongst the realists, is immaterial to the issue at hand. Hence, I will not engage it here.

By “matter,” I here mean “prime matter,” which Aristotle understand to be nothing but the potential to be something concrete. The term “prime” or “primary” matter is meant to differentiate this concept of matter from the more common referents for matter, such as stone or wood or even the elements, which Aristotle considers secondary matter. These are secondary because they are not matter per se but matter with formal properties, which is what makes them concrete and perceptible. Passages in which Aristotle treats prime matter as synonymous with potential include: Physica, 217a22ff; and Metaphysica, 1092a3. The traditional reading of Aristotle on matter as potential, which I advocate, has been challenged. C. J. F. Williams suggests that “Aristotle seems to dissociate himself from the sorts of views which are involved in the traditional doctrine of prime matter.” C. J. F. Williams, Aristotle’s De Generation et Corruptione, trans. Oxford, 1982): 216. Other opponents of the view include H. R. King, “Aristotle without prima materia,” Journal of the History of Ideas 17 (1956), 370-89; and W. Charlton, Aristotle: Physics Books I and II (Oxford, 1970), 129-45. Central to the anti-traditional case is that Aristotle suggests elements generate from other elements (e.g., air from water); hence, there is no substratum of potential, only elements generating elements, which mingle into more complex substances. Rebuttals in defense of the traditional view include: F. Solmsen, “Aristotle and Prime Matter: A Reply to Hugh R. King,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 19 (1958): 243-52; A. R. Lacey, Journal of the History of Ideas 26(1965); and H. M. Robinson, “Prime matter in Aristotle,” Phronesis 17 (1974): 97-101. The main deficiency of the anti-traditional reading is that it expects Aristotle to speak about prime matter as something that is actual and perceptible. Hence, when Aristotle talks about the most basic actual and perceptible matter as the elements, these authors take this as proof that Aristotle is an elementalist, seeing nothing more basic than the elements themselves. Yet, as Solmsen points out, Aristotle distinguishes actuality from potentiality, identifying matter with the latter, which is why one should never expect to find Aristotle speaking about prime matter as “actually” present in the world (243); talk of actual matter requires one to speak about matter with form. Likewise, perception works on properties, or form (245), which is why prime matter is only ever grasped by analogy and is not perceptible as such (244). Hence, according to Aristotle, even the simplest bodies are “perceivable bodies” (Physica 204b32; De gen. Et corr. 329b7); for if they are actual, then they are matter with form, and the latter makes them perceptible. But the fact remains that Aristotle explicitly identifies matter with potential in several passages (noted above). As for Aristotle’s insistence that elements give rise to elements, Aristotle’s answer to whether matter remains selfsame in this process is only intelligible through the traditional reading. He replies, “Perhaps the solution is that their matter is in one sense the same, but in another sense different. For that which underlies them, whatever its nature may be qua underlying them, is the same: but its actual being is not the same.” (On Generation, 319a29-a33, trans. H. H. Joachim). Such an answer presumes there is a matter beneath the elements, so that as one element comes to be and the other passes away, the secondary matter is not the same, but the primary matter beneath both is the same. Aristotle makes the same point in De caelo, 312a30-33; see also Physica, 329a23ff. Finally, it is worth noting, as Solmsen does, that Aristotle explicitly differentiates his concept of a substratum from that of Anaximander’s Infinite and Plato’s receptacle, specifically by noting that his concept of substratum does not ascribe actuality to the substratum (249). His substratum, as pure potential, cannot actually exist without being informed: Aristotle, Physica, 329a8-13; a24-6. Were Aristotle an elementalist, he could not say this. On these same points, see also Robison, “Prime Matter in Aristotle,” passim.

See section 3 of “The Metaphysical Idealism of the Eastern Church Fathers.”

For more on medieval modal logic, see my Substack letter, “Reflections on the Ontological Argument: Is it Nicene?”

Aquinas, ST, I, q.25, a.4.

Anselm’s ontological argument appears in his Proslogion, passim, esp. chs. 2-3. For a summary and assessment of the argument, see my “Reflections on the Ontological Argument: Is it Nicene?”

Formally written, the distribution axiom runs as follows: □(p→q)→(□p→□q). “□” means necessarily and “→” means if-then.

See, e.g., G. W. Leibniz, Die philosophischen Schriften von Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, ed. C. I. Gerhardt, 7 vols. (Berlin, 1875-90), vol. 6, 117

I flesh out this concept further in my Substack letter, “To a Woman Who Lost Several Children.”

See, e.g., Arthur Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being (Harvard University Press, 1936), 52.

Nathan A. Jacobs, “The Begotten-Not-Made Distinction in the Eastern Pro-Nicenes” Religious Studies 55:4 (2019), 517-19.

William James discusses these points in his lecture, “The Will to Believe.”

Peter L. Berger, A Rumor of Angels (Doubleday, 1966), 6.

Berger, A Rumor of Angels, 7.

Berger, A Rumor of Angels, 7-8.

I’m new to your Substack and analytic idealism of Bernardo Kastrup helped open my mind to Eastern Orthodox Christianity. There are no fairies, or even God, under the prevailing materialist/physicalist paradigm of reality. Indeed, they are called miracles because they don’t fit into the paradigm of reality. That paradigm of reality sucks and is fake news. Consciousness is fundamental, expressed as various formulations of “idealism.” Things are no longer miracles because their occurrence fits within consciousness all around us, containing information even Rupert Sheldrake’s dogs can access. All now have been proven real in “six sigma” rated studies: 1) remote viewing, 2) telepathy, 3) precognition and 4) psychokinesis. Hard to argue fairies aren’t equally possible in consciousness; considering the other side of science coin. Just like non-dual awareness. Rupert Sheldrake is on Facebook in the last week asserting that Steven Pinker refuses to debate him about the science.