The following email is to an inquirer about the gnomic will in Maximus the Confessor. “Eli” had seen a lot of discussion about the topic online and found it all rather confusing. He asked if I was able to make this complex topic a little less perplexing and more intelligible. The following is my attempt to do just that. Please subscribe and support my work.

Dear “Eli,”

I’m always surprised that the topic of the gnomic will is a point of interest for so many. I, personally, find the topic to be a bit obscure — not to say that it’s unimportant. But it always surprises me how many folks latch hold of the subject with tenacious interest.

I’m happy to do what I can to illuminate the issue. My personal take is that the topic and the Orthodox claims thereabout are not terribly complicated. What makes the topic confusing for so many is the technical language involved, which is alien to most, and the fact that this language is fluid throughout the historical debate, shifting meanings, depending on the context. If one can successfully navigate these nuances, however, I do not think the content of the dispute is nearly as complicated as it seems. You can tell me whether you agree after reading my efforts to clarify it for you.

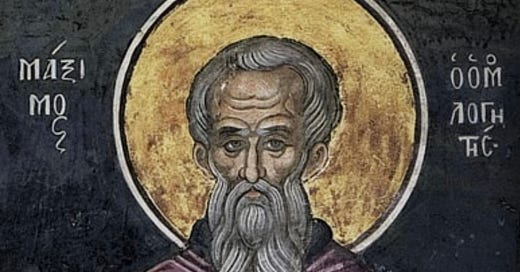

As I’m sure you know, the dispute that occasioned the gnomic will discussion is the controversy is this. In the wake of Chalcedon, the whole of Syria broke away from the Church, fearing that Chalcedon conceded too much to the Nestorians. Sergius I, patriarchate of Constantinople, looked for a means of reunification with the non-Chalcedonians. His initial proposal, monoenergeism (i.e., Christ has only one energy), gained initial support but faltered under opposition from Sophronius — especially after his elevation to patriarchate of Jerusalem. But after Sophronius’ repose, Sergius floated a new proposal, monotheleitism, the doctrine that Christ has only one will. The proposal garnered initial support from the then-patriarchate of Rome, Honorius I, and quickly gained traction. It was this heresy that Maximus the Confessor, along with the the successors of Honorius — Theodore and Martin — combatted. And it’s in the context of this opposition that Maximus discusses whether Christ has a gnomic will. Before looking at Maximus, however, let’s first look at the main problems with the monothelite proposal.

According to monothelitism, Christ has only one thelēma and one thelēsis, two words for will. The obvious worry the doctrine raises is that it seems to deny the two natures of Christ, since to will belongs to both God and man. If Christ is fully God and fully human, then he should have a divine will and a human will. If he has only one, then it seems he did not take on the volitional aspects of our human nature. In this light, the teaching looks to be a rehashed version of Apollinarianism, where the union of the two natures is achieved by removing one aspect of human nature and replacing it with that same aspect from the divine nature. In the case of Apollinaris, the rational spirit, or mind, is replaced with the Logos, Himself a rational spirit. In the case of monothelitism, we see the same strategy: Remove the human will and replace it with the divine will. But the problems with such strategies are always the same. First, they deny the full humanity of Christ. Apollinaris’ Christ is not human; he is a mindless animal that appears human, as Gregory of Nazianzus et al. point out. So it would be in the case of the monothelite Christ; he would not be fully human, since will is an essential property of human nature. Second, and closely related, the Eastern fathers understand Christ to take on our nature in order to heal that nature. But as Gregory points out, contra Apollinaris, Whatever is not appropriated is not healed. If Christ did not take on our mind — here replying to Apollinaris — then our mind is not healed. So the same rationale applies to monothelitism: If Christ did not take on our will, then our will is not healed.

Now, there are legitimate questions about whether a denial of the two natures of Christ was in the mind of every monothelite. When, for example, Pope Honorius affirms monothelitism by saying that Christ is one, so his willing is one, since he cannot be divided against himself, it’s not clear he is saying anything heretical. The statement could be an affirmation that Christ is only one hypostasis, so only one subject ever wills, even if he has two types of will. This would be true. So, clarification is required. But our concern here is not with the monothelites, but with the Orthodox position espoused by Maximus and upheld at Constantinople III.

So, turning to Maximus, rather than begin with the gnomic will, I’d like to begin with his discussion of will more generally and back our way into the gnomic will discussion. Maximus points to Gethsemane in particular, arguing that Christ’s own words, Not my will but your will be done, indicate a distinction between his divine will and his human will. — This observation is nothing new. The type of distinction Maximus sees here appears in other fathers, such as Cyril of Alexandria, when noting the grief in spirit that Christ experiences on the way to his crucifixion, or in Gregory of Nyssa, when pointing out to Apollinaris the numerous passibilities Christ experiences in the Gospels. — But how are we to understand this distinction of wills? Clearly, there is the basic distinction that one will is human in nature, while the other will is divine in nature. But what is the relationship between the two types of will in Christ? Here, we enter the technical terminology of the dispute.

I’ll begin with the term orekikēn. Orekikēn is a faculty of desire. This faculty, Maximus suggests, is something native to all living beings. Strange as it may sound, we could say, for example, that a plant has a desire for photosynthesis. We might think of it as a natural drive in accord with the nature of the thing — akin to the way Aristotle sees teleology driving the formation of organisms. A new dimension opens up, however, when natural desire is combined with reason (logikē). For reason brings with it the unique capacity for self-determination (to autexousion). That is, unlike plants or irrational animals that naturally develop in accord with their nature, rational beings have a capacity to examine their own nature and desires and choose whether or not to move in accord with such desires — an exceedingly odd capacity, if you think about it, but one we are so accustomed to that it rarely strikes us as extraordinary! Such self-determination is what sets human beings apart from the rest of the organic world. On this point, Maximus is far from unique. The Eastern fathers commonly refer to rational beings as self-determining. Such is the nature of free will.

Now, this brings us to the two words for “will” noted above, thelēma and thelēsis. The former term, thelēma, is a general term thattypically refers to the will as such — that is, as a generic faculty native to human nature. When we speak of human volition or will (i.e., as a common feature of our common nature), the term for that faculty is thelēma.

Thelēsis is a bit more specific. Thelēsis refers to rational desires (as opposed to just any natural desires) that lead to rational action. This, Maximus tells us, encompasseses willing, thinking, wishing, judging, inclining toward, choosing, moving toward, and using. (We find this same list in later fathers, such as John of Damascus, who also works through which of these acts overlap with the divine will and which are alien to the divine will. Any act rooted in ignorance, for example, is inevitably alien to divine volition, a point that will be relevant to the gnomic will discussion.)

While any of the above acts fall under thelēsis, Maximus suggests that there are certain primary acts or modes of thelēsis. Here, wishing and choosing stand out as primary, according to Maximus. The former, wishing, is an imaginative desire that explores what one might choose unencumbered by circumstance. If, for example, I’m hungry and imagine what I would like to eat, I may answer with something that is not presently in my capacity to choose — a Giordano’s pizza, for example. Because there are no Giordano’s restaurants in my state, that wish is not within my capacity to achieve. Choosing, as contrasted with wishing, concerns the more narrow range of possibilities that are actually within my power. Hence, I may redirect my wish for Giordano’s pizza toward the next best pizza chain near me. Thus, while thelēsis covers a variety of other activities, we primarily think of it as engaging in the imaginative activities of what I might choose unencumbered and what I will choose, given the realities on the ground.

Now, this brings us to our next distinction, namely, the distinction between the natural and the gnomic will (gnōmikon thelēma) — the latter, of course, being the reason you wrote to me. As noted above, the main cause of confusion, in my estimate, is the fluidity of language on this topic. The word gnomē is itself a dynamic word, and Maximus himself changes his meaning depending on whether he is writing in a polemical or a non-polemic context. Once we nail down the various meanings, however, the claims become clear.

Let’s begin with the natural versus the gnomic will in its most generic sense. This distinction concerns the generic faculty of will, on the one hand, and the idiosyncratic use of that faculty, on the other. We might think of it as analogous to speech. You and have I have a common power of speech, one native to our common human nature. However, I use that capacity for speech in idiosyncratic ways, ways different from the ways you use that capacity. So, we could draw a distinction between the natural power of speech, which we share, and my gnomic speech, which is my idiosyncratic use. So it is with the will. As human, you and I each have a natural power of volition — that is, a “natural will” — since to will belongs to man. But we use the power to will in idiosyncratic ways, reflected in our idiosyncratic choices. The common faculty that we share is the natural will, while our idiosyncratic use of will is the gnomic will.

Incidentally, this is par for the course with Eastern patristic realism. For a full treatment of this brand of realism, see my article, “The Metaphysical Idealism of the Eastern Church Fathers.” But for our purposes, let it suffice that the Eastern fathers insist that the common nature shared by several subjects is numerically one. Think, for example, of Gregory of Nyssa’s letter to Ablabius. When asked whether Timothy, Paul, and Silvanus are three humans, his answer is No. They are one human, the common nature, or ousia, being numerically one. Several subjects, or hypostases, have that nature, but the nature they share is one, not several. The point is critical to Eastern patristic soteriology. Christ took on, not an insulated, particularized nature, but our nature — the nature that is in you and me — so that he might heal it. The unity of nature across the species is critical to the gospel, as the Eastern fathers understand it. So, in keeping with this line of thinking, they also draw a distinction between the nature that we share and our idiosyncratic use of that nature. And such a distinction extends to specific aspects of that nature. Our power of speech is common but our use is idiosyncratic. Mind is common but the use is idiosyncratic. And so it is with will: Will is common but the use is idiosyncratic. Such is the basic line of thinking in the natural-gnomic will distinction.

Unfortunately, this rather basic distinction became more complicated during the monothelite controversy. For Maximus also uses gnomē to refer to two further phenomena. The first is a rational impulse or movement or inclination of reason toward p over q. (Notice that “inclining toward” was one activity of thelēsis in that long list above.)So, for example, if I have a rational inclination for pie over cake, this rational inclination or movement or impulse is also identified with the gnomic will in Maximus. It is my idiosyncratic rational inclination.

Now, as an important aside, some are tempted to use this meaning of gnomic will to read Maximus as a determinist — specifically a compatibilist (on the meaning of “compatibilist” and other cognates, see my post “On Free Will”). That is to say, Maximus grants that we have “choice,” but he believes we have inclining impulses underneath those choices that are determinative; hence we choose p over q, but that choice is a reflection of the innate inclination that determines our choice. Such a reading simply isn’t viable, for a variety of reasons. The first is that the rational inclination is self-determined, according to Maximus. That is, the inclination reflects both present rational judgments, which are themselves free operations, as well as past choices, which are prior self-determinations. In other words, my own free activities are what establish the rational inclination in the first place; the inclination does not establish or determine my choices. In short, a determinist reading would invert the causal order.

The second reason the determinist take isn’t viable is that gnomē is an inclination, not a choice. The distinction is important. A consistent claim throughout the Eastern Church fathers is that aspects of our nature incline but do not determine our choices. The point is often made in reference to the passions. In other words, the fathers recognize that things like the passions hold sway over our will and make it easier to choose in accord with them than to resist them. But the fathers categorically deny that such sway is determinative of choice. Only the will can determine the choices of the will. Inclining influences make contrary choices harder, but never impossible. So here, Maximus is acknowledging that lower passions are not the only inclining influence. Our rational desires and past habits of reason are also inclining influences. Yet, Maximus, like the other fathers, is clear that these inclining influences do not determine the will.

We can see the point quite clearly in Maximus’ claim that the inclinations of rational desire are cumulative. He says that past choices have a vote in future choices, and in this sense, past choices have a compounding effect — repetition of reasoning and choice strengthens the inclination. The notion of a vote and compounding influence indicates that the inclination is not determinative. Were an inclination sufficient to determine my activities, then there would be no sense in claiming that its sway becomes greater with repetition. What greater sway could it possibly have than to determine my choices? Hence, while repetition builds an idiosyncratic inclination, this rational inclination does not undo the self-determining nature of the will; the will retains its capacity to choose and self-determine, even when a choice contrary to our rational leanings becomes difficult.1

Returning to the subject at hand, however, Maximus’ use of gnomē takes one further meaning amid the controversy, namely, susceptibility toward evil. In this polemical context, the gnomic will — and sometimes the word “choice” (prhairesis) — came to be associated with the capacity to choose either good or evil. Here, the terminology becomes very specific. Gnomic will and choice in this context is not about the idiosyncratic use of will, nor is it about rational inclinations generally; it is about a very specific mode of choice, namely, the susceptibility to evil. In this context, to say that one has a gnomic will is to say that one can turn from the good and embrace sin, becoming morally and spiritually corrupt, as did the Devil or Adam.

So, with these terms before us, let’s look at the controversy over the gnomic will. What draws attention to Maximus on this topic is that, in polemical texts, Maximus denies that Christ has a gnomic will. In such texts, he even denies that Christ has choice (prhairesis). Is Maximus denying that Christ has free will? Before invoking the more technical content discussed above, allow me to offer a commonsense reply. Maximus represents the side of the dispute that affirms that Christ has two wills and that his human will has significance. Therefore, it would be a strange thing indeed for Maximus to deny Christ some aspect of will — especially something so central as free choice! — since such a denial is the very thing he is battling against. So, prime facie, it seemssomething else must be going on here.

Toward this end, when Maximus denies that Christ has a gnomic will and choice, he is using these terms in the last sense described above, namely, as susceptibility to evil. Maximus denies Christ has inquisitive (zētikēn) desire — that is to say, that Christ is ignorant of the good and thus susceptible to the sways of sin. So, when speaking about whether Christ might turn from the good and become corrupt, Maximus answers No, insisting that Christ does not have a gnomic will nor does he have choice.

Now, there is nothing new here. Within the Arian controversy, a critical metaphysical commitment emerges, one that is central to the thinking of the Eastern fathers generally. To wit, every creature qua creature begins its existence with a movement into being. Such a movement is a mutation, a transition from not-yet-something to something. And this transition means that, of metaphysical necessity, every creature is mutable, or subject to change. The goods we possess we have by acquisition; they are not native to us. And so, every good we possess or acquire we can also be deprived of. In the case of free beings, this mutability includes moral and spiritual goods. Rational beings, as images of God that are made to participate in the attributes of their divine archetype, must freely cling to God in order to acquire these moral and spiritual goods, but being self-determining, we may also turn away from God and become spiritually corrupt. This metaphysical necessity (i.e., that we are mutable and thus corruptible) is native to every creature as such, and not even God can make it otherwise — a point that becomes evident in the Arian dispute (see any number of my articles, such as my entries on Athanasius or the Cappadocians, my piece on the free will defense, or my treatment of the metaphysics of God and creatures).2

This metaphysical necessity is what sets the stage for the Eastern patristic understanding of the gospel. While it is true that the Incarnation is meant to remedy the corruption that set in as a result of the Fall, the participation in God that is made possible by the Incarnation was required even before the Fall. In other words, even before corruption set in, the threat of corruption hung over the head of every creature qua creature. Even before any being turns away from God, our turnability itself is a looming threat. So, the question emerges, How is one to ever escape, not just actual corruption, but the ever looming threat of corruption — that is, our innate corruptibility? Such a question is one the Eastern fathers are attuned to, and we can see this in the Arian controversy, the Appolinarian controversy, and even the Origenist controversy. The answer to the question is that we must partake of the only nature that is incorruptible and unturnably Good, namely, God’s own nature. Only by participating in this nature can we cast off, not only our corruption, but the very threat of corruption, becoming incorrupt and unturnable in goodness.

This is why Athanasius harps on the point that Arius’ Christ, having come into being, is mutable (alloiōtos) and spiritually turnable (treptos). If the Son is a creature, then he is bound by the same metaphysical necessities we are — including corruptibility and spiritual turnability. His goodness is acquired and not his own; he can at best participate in divine goodness and incorruption, but it is not native to his nature, which means a union with his nature does not provide access to incorruption. The point echoes in Alexander of Alexandria and in the anathemas of Nicea itself. Contra Apollinaris, Gregory of Nyssa complains that, in denying Christ a human mind, Apollinaris makes the passibility of the Son native to his divine Mind, which is to ascribe mutability and thus corruptibility to the Son. So, Gregory argues, Apollinaris likewise undermines our hope of incorruption with such a doctrine. And Maximus the Confessor himself, when speaking of Origenistic cosmic cycles, expresses the worry that if the world, after being reconciled to God, can fall again, then this undermines our hope of incorruption.

The reason I point this out is that there is a consistent thread before Maximus that insists the Son is incorruptible and spiritually unturnable (atreptos), and that this unturnability is central to Christian hope. So, denying that the Son is susceptible to the sways of evil — that he does not have a gnomic will or choice in this sense — is nothing new. Now, one might reply that, in taking on a human will, he must also take on such susceptibility. The mistake I see in this line of thinking is twofold.

First, it tends to think of the will as if it is a subject, or hypostasis. Keep in mind the above distinction between natural and gnomic will — here “gnomic will” referring to the idiosyncratic use of volition. Will is nothing more than a generic power, a feature of human nature. Will in this generic sense does not choose anything. Hypostases use the will, making choices. When hearing that Christ has two wills, some folks slip into a Nestorian mode of thinking, as if Christ is two individuals in dialogue about what to choose. But this is not the case. Christs is only one subject. Therefore, while he has two types of will — a divine will and a human will — only one subject ever wills anything. So there is a requisite harmony between the wills, since only one ever uses both. Perhaps the framing of the question may help. Rather than asking, as some do, Is human volition susceptible to evil?, we should ask, Is the Son of God susceptible to the sways of evil? While the former question beckons a Yes, the latter beckons a No. And this, I think, captures the point of confusion: The generic human will does not choose anything; the Son of God wills things, and he is not susceptible to the sways of evil.

The second point of confusion is the tendency to see corruptibility as a positive property, one that is essential to human nature. Thus, if the Son lacks corruptibility, or if his will is unturnably good, then he is not fully human. This line of thinking fails at two points. The first is that corruptibility or mutability is not a positive attribute, metaphysically speaking. The proper formation of our nature toward which we move in the generative process is a positive metaphysical reality; divergence from it is privative, being negatively defined by that which it diverges from — akin to the way blindness is not an additive property to the eye. Hence, to “deprive” us of corruptibility is not to remove an essential property from our nature.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, incorruption and unturnability is in fact part of the teleological end of man, according to Eastern patristic thought. Unlike in Western thinking, with the nature-grace divide introduced by Augustine, wherein grace is a supernatural good that God might voluntarily give or withhold, since we have no right to it, the Eastern fathers understand us to have a natural and unbreakable connection with the divine nature — the energies of which are uncreated grace (as contrasted with the created grace of the West). According to the Eastern fathers, an image or icon has an essential connection with its archetype. When defining what an image is, the answer is referential: It is the image of [name the archetype]. This essential connection as image is also what makes the image susceptible to the attributes of its archetype — a reflection participating in the attributes of that which it reflects, for example. Hence, man as an icon of God has an essential connection with his divine archetype, one that makes him susceptible to the divine attributes (see, again, my piece on the metaphysical idealism of the Eastern fathers for more on this). Now, admittedly, our participation in divine attributes requires active imitation of God, a free participation in our archetype, which is why we are not incorrupt from the start but must willfully move into incorruption (see my piece on the free will defense, as well as my article on whether the soul is immortal). But the fact that such willful participation is requisite for the participation in these attributes does not change the fact that such participation is part of the teleological end of our nature as icons of God. Hence, Christ, in communicating incorruption and unturnability to our nature in no ways does violence to that nature. Far from being a form of monophysitism, where something of our humanity is compromised, this is in fact a fulfillment of our nature, making it more fully human than it was before.

Taking the above points into account, then, we should not be surprised to find that Maximus denies that Christ has a gnomic will or choice in the sense of susceptibility to evil. Remember, Christ took on our will in order to heal it. Communicating his divine unturnability to it is the very healing here referenced.

Yet, in saying this, is Maximus denying that Christ has free choice more generally? This question really comes down to a question of whether God, being “incapable” of evil, has free will. (I place “incapable” in quotes because the error here, again, is to treat the choosing of evil as a positive power as opposed to a privative one.) Clearly, the Eastern fathers insist that God has the power of contrary choice (prhairesis), despite evil not being amongst the spectrum of his possible choices. We can see this in numerous places. Basil of Caesarea, in his Hexaemeron, says plainly that God creates by choice. Moreover, in his polemics against the Eunomians, Basil suggests that we cannot have any power superior to those of God, our cause; hence, we could not have the extraordinary power of free choice unless God himself had free choice. Saint Macrina, too, refers to the “impulse of divine choice.” Gregory of Nyssa, in his Great Catechism, refers to the Son’s capacities of mind and will to prove that he is a hypostasis — to name just a few examples. But in all such instances, the Eastern fathers understand, as Athanasius explains, that God always freely chooses in keeping with his nature. In other words, while God freely expresses his nature through choice, the nature expressed is immune to evil, and thus the articulations of that nature are always reflective of his Goodness. Keep in mind, for the Eastern fathers, goodness, virtue, holiness, and the like are divine in nature; these are energies. We as images of God must therefore cling to these energies and the source of these attributes, Who is extrinsic to us. For God, however, these energies spring from his intrinsic nature, expressing the nature he has innately. I see nothing in Maximus that moves contrary to this idea of divine freedom.

Since we’ve covered quite a bit, perhaps it might help to offer a brief summary of Maximus’ position before closing out this letter. Maximus insists, in keeping with Chalcedon, that Christ is one hypostasis but has two natures, divinity and humanity. Maximus also recognizes that to will belongs to both God and man. Therefore, having both natures, Christ must have two wills, a divine will and a human will. In saying this, Maximus is not claiming that Christ is two hypostases working in cooperation, as would be the case in Nestorianism; rather, there is only one hypostasis, the Son of God, who wills; but his willing involves two types of will. Both divinity and humanity, being volitional natures, have free choice and self-determination, and so the Son, too, having both types of will, has both types of freedom. In keeping with this affirmation that the Son is free, we can draw a distinction between the generic faculties of will he bears — both divine and human — and the Son’s idiosyncratic use of these wills — this being the non-polemical distinction between the natural and gnomic will. However, the Son, being Wisdom herself, is not ignorant of the Good, and joining humanity with his divine, incorruptible nature, thereby healing it, is not susceptible to the sways of sin. This is not to say that the Son, in his humanity, does not feel the natural and blameless passions, such as the recoiling from death, expressed in his grief at his impending crucifixion or his prayer at Gethsemane. But it is to say that his human will, despite any experience of natural and blameless passion, cannot be turned from the Good — a fact expressed in his words, Not my will but thy will be done, indicating a harmony between his divine and human wills within the one hypostasis, the Son of God. In this more specific sense, then, the Son does not have a gnomic will or choice, here using these terms to refer to moral and spiritual turnability.

I hope that clears things up.

Sincerely,

Dr. Jacobs

—

Nathan A. Jacobs, Ph.D.

Scholar in Residence of Philosophy and Religion in the Religion in the Arts and Contemporary Culture Program (RACC)

Vanderbilt University, Divinity School

http://nathanajacobs.com

https://vanderbilt.academia.edu/NathanAJacobs

The following aside was part of the original body of the letter. However, looking at it now, I think it creates too long of an interruption in the flow of thought. So, I have moved it to this footnote, keeping the content for those interested, but allowing it to be passed over by those less interested: This talk of compounding inclinations based on prior choices likely raises the question of whether Maximus is describing the Aristotelian theory of habit. That is, according to Aristotle, we form virtue by repetition, which develops a habit of choosing rightly, and in this way, we learn to love virtue, even though it is initially quite difficult — akin to the way learning piano is difficult at first but one comes to enjoy it the more natural the practice becomes. Is this what’s going on in Maximus’ talk of gnomē as inclination? Certainly, there is some resonance with the theory. And some scholars do wonder whether, on this point, as well as in Maximus’ talk of wishing, there is an Aristotelian influence — though, when it comes to wishing, I wonder about Stoic influence. It’s difficult to say. Some speculate in the affirmative. David Bradshaw theorizes that it’s an indirect Aristotelian influence, transmitted through another father, such as Nemesius of Emesa, for example. We really don’t know. However, there are critical differences between the Aristotelian theory of virtue as habit and Maximus’ ontology. I don’t want to get too sidetracked here, so I’ll try to keep this brief. For Aristotle, virtue appears to be the formation of a natural potency, akin to the way I might develop an intellectual capacity or artistic skill. Maximus’ understanding of virtue, by contrast, is synergistic. We can see this in his doctrine of the logoi. According to this doctrine — and you can get a more thorough summary of it in my aforementioned article on the metaphysical idealism of the Eastern fathers — God generates concepts or words of the things he intends to create before he makes them. This is similar to the Platonic notion of divine Ideas that precede the creation and serve as archetypes for the things of this world. But the Christianized version of the doctrine in Maximus — and those before him — presumes that God does not merely generate archetypes of generics, such as circle or human or cat, but of particular subjects. He chooses to make you and me. And with that choice comes an archetypal picture of what you and I are to become, not merely a generic idyllic picture of human. Just as in Platonism, where the Form circle serves as the measure of whether a particular drawing of a circle is good or bad, well-formed or malformed, so my logos serves as the measure of whether my formation over time is good or bad. In this context, Maximus discusses the tropos, or modes of being: Movements that are in keeping with my logos are well-being, moving toward eternal well being, while divergent movements are corrupt. Because the logoi are part of God (a part I argue in that metaphysical idealism piece), and I, as an image of my logos can participate in this archetype (also argued in that piece), my participation in my logos through moves of well-beingis ultimately a participation in God. Hence, modes of being that form me in virtue are not merely a natural capacity moving into being, it is a participation in God. This is why I say that the underlying ontology of virtue is synergistic in nature. (Incidentally, I think this is par for the course with the Eastern fathers; true virtue is always a partaking of the divine nature, and thus is always synergistic.) All this is to say that, while there is some resonance with Aristotle on the point that a repetition of choice produces a compounding rational inclination, one that can either bend us toward good or ill, the underlying ontology of virtue is significantly different.

The opponents of Arius consistently run through the metaphysical entailments of Arianism, namely, that if the Son is a creature, then he is mutable and corruptible. And though Arius, later in the dispute, pivots to argue that the Son is created immutable, the retort comes that this is metaphysically impossible.