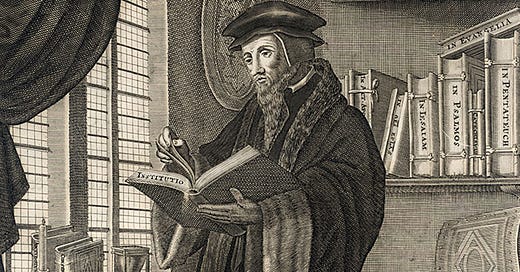

The following is not a letter but some research that I never got around to publishing. Common amongst contemporary “Calvinists” is the view that those whom God has predestined to salvation also persevere in the faith. That is to say, having been predestined to be saved, God brings them to faith and does so in such a way that they persevere to the end. On this view, it is impossible that one might come to saving faith, then fall away from faith and be damned. For this reason, contemporary “Calvinists” tend to see New Testament warnings to not fall away as “problem passages” (i.e., passages that appear to run counter to their doctrine and must therefore be explained in a way that coheres with the doctrine of predestination so understood). The most common approach to such passages today is something like the following. Paul assures his readers that they have been saved, but he places this statement in the conditional, indicating that if they fall away, they have believed in vain (e.g., 1 Cor. 15:2). Many “Calvinists” read such passages as applying a conditional to Paul’s understanding of the reader’s faith — they have believed and are saved, unless they fall away; in which case, their faith was not genuine, and they were never saved. I am no “Calvinist” nor am I Reformed. Nonetheless, from a purely historical perspective, I find it intriguing that the contemporary approach to such problem passages by contemporary “Calvinists” is divergent from Calvin’s own view. In what follows, I offer part 2 of a three part look at what Calvin has to say about such passages and highlight the differences between his approach and the more contemporary approach. To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing; to my paid subscribers, thank you for your support; to everyone else, please consider subscribing and supporting my work!

2. Calvin on the Phenomenon of Temporary Faith

What is the cause of temporary faith in Calvin’s view? He is quite clear that the will of man is so thoroughly corrupt as to be incapable of choosing the good on its own. As he puts it in the Institutes, “Because of the bondage of sin by which the will is held bound, it cannot move toward good, much less apply itself thereto; for a movement of this sort is the beginning of conversion to God.”1 Yet, if Simon was genuinely inclined toward Christ so as to “willingly enlist under him,”2 was this not a movement toward the good? How is this possible if Simon is a reprobate? Calvin’s answer differentiates Simon’s contribution to the event from God’s contribution.

Beginning with Simon’s contribution, Calvin affirms that Simon willfully participated in temporary submission to Christ. As mentioned earlier, Calvin speaks of Simon as willingly enlisting himself under Christ, “for when he was convicted he gave Christ his hand in earnest.”3 But Calvin also blames Simon for withholding his heart from Christ during this time of transitory faith: “And yet [Simon] giveth not himself over sincerely to Christ.”4 In this sense, Simon is ultimately credited with the faulty nature of his faith and its eventual falter—though he willingly gave himself over to Christ, it was Simon who withheld his heart and refused “the denial of himself.”5

Nevertheless, Calvin does not attribute the whole of the matter to Simon. For even a faulty faith in Christ is a good that comes from God alone. As Calvin puts it, “it is the Lord who pierces the ears, (Psalm 40:7) and that no man obtains or accomplishes this by his own industry.”6 Calvin’s talk of Simon’s transient conversion describes it as a winning over, overcoming, or overwhelming. As for the means for achieving this overwhelming, Calvin highlights both the preaching of the gospel by Philip—“the very doctrine which is contained in his word shall purchase authority for itself”7—and the miracles that accompanied the message—“there was also another prick whereby they were pricked forward, and that was miracles.”8 In these testimonies, we find the instruments for the winning over of Simon. Calvin writes, “conquered by the majesty of the gospel, he showed a certain sort of faith, and thus recognized Christ to be the author of life and salvation.”9 And again, Simon was “enforced to give glory to the true miracles.”10 Language of winning over is common to Calvin’s talk of temporary faith. We find similar language in Calvin’s comments on Psalm 106, for example, which recounts the temporary faith of the Israelites who, after witnessing God’s miracles and “believing,” eventually abandoned their faith. Calvin speaks of these temporary believers as “being convinced by such indubitable testimony,” and being “Overpowered by the grandeur of God’s works.”11

For Simon and these Israelites, their temporary faith arose in response to the work of the word and the Spirit; yet, this work was a “lower” work of the Spirit when compared with the work of regeneration. What these reprobates experienced was a winning over to the truth by the miraculous works of God, but this winning over did accompany regeneration. Simon, therefore, “had not tasted the first principles of godliness.”12 His experience was a genuine experience of illumination by the Spirit and tasting of divine grace, despite this taste falling short of regeneration.

In his treatment of Hebrews 6:4, Calvin reiterates the point: “He calls it illumination a tasting of the heavenly gift; … He calls it participation of the Spirit; … He calls it a tasting of the good word of God; … And lastly, he calls it a tasting of the powers of the world to come.”13 Such language, when applied to the apostate, raises the question for Calvin, “how can it be that he who has once made such a progress should afterwards fall away?”14 Calvin answers, “That God indeed favors none but the elect alone with the Spirit of regeneration.”15 What we see, then, is Calvin’s willingness to affirm the work of the Spirit in those who fall away; their final reprobation is no reason to deny God’s work in transient faith: “But I cannot admit that all this is any reason why [God] should not grant the reprobate also some taste of his grace, why he should not irradiate their minds with some sparks of his light, why he should not give them some perception of his goodness, and in some sort engrave his word on their hearts.”16

Here, we can see how Calvin couples Simon’s subtle “hypocrisy” and the divine act of illumination. Simon’s experience of divine illumination was sufficient to prompt a superficial belief, but it was insufficient for the transformation of his will. His belief was genuine and genuinely brought about by the Spirit, but in his lack of regeneration, his depravity was equally genuine: “it appeareth that he is a profane man, and such as had not tasted the first principles of godliness; for he is touched with no desire of God’s glory.”17 Calvin sees Simon’s lack of concern for God’s glory in his attempt to purchase the Holy Spirit. This failing, thinks Calvin, was a manifestation of vain ambition. It demonstrates, to Calvin’s mind, that Simon merely saw the apostolic powers as superior to his own magic; hence, his submission to Christ was driven by vain glory and greed: “For that ambition which was hidden before breaketh out now, when as he desireth to be equal with the apostles. This is now one vice; another is, because while he thinketh that the grace of God is to be sold, he will get some greedy gain thereby.”18

Calvin offers a similar narrative in his comments on Psalm 106. After making clear that the Israelites had been won over by the power of God, Calvin writes,

… [T]hey yet instantly resumed their wonted disposition of mind, and began to rebel against God, as if they had never beheld his wonderful works…. Overpowered by the grandeur of God’s works, they were, he says, in spite of themselves, compelled to believe in God, and give glory to him, and thus the criminality of their rebellion was increased; because, although their stubbornness was overcome, yet they immediately relapsed into their former state of unbelief.19

In short, Calvin takes the falling away of the apostate to demonstration, not a disingenuous experience, but an insufficient experience: They were never regenerated. And without a transformed will, apostasy is inevitable.

What we are left with is the conclusion that the reprobate is won over to transient faith by the power of God—Simon is forced to glorify the works of the Spirit; yet, the sin that follows in apostasy is not the work of God in a direct sense. Simon willed his own demise. Put otherwise, God is the efficient cause of faith, while Simon is the deficient cause of apostasy. Of course, for Calvin, without the work of regeneration, Simon can do no other. Man sins out of necessity. For without regeneration, “the will is held bound, it cannot move toward good, much less apply itself thereto.”20 This necessity should not be taken to mean that Simon did not will his demise, however. Calvin is quite clear on this point, “For man, when he gave himself over to this necessity, was not deprived of will.”21 Indeed, the will is an inalienable feature, or essential property, of humanity—“to will is of man.”22 The Fall does not deprive man of the faculty of will, but it does deprive man of a good will. Thus, while the power of choice remains within us, excluded from that power is the choice to change our corrupt condition. Hence, fallen man is given over to the necessity of evil: “to will ill, [is] of a corrupt nature.”23

Now, it is important to note Calvin’s distinction between the necessity of sin that follows from the Fall and compulsion. According to Calvin, we sin out of necessity—apart from regeneration, we are incapable of raising our affections to God—but this does not mean that we sin out of compulsion. The sins we commit, we choose.24 We are bound to will in accord with, what Calvin calls, our “corrupt affections.”25 Here we see a certain form of compatibilism emerge. Though our will is crippled by the Fall, resulting in a narrowed spectrum of choice, our choosing is still free because we choose in accord with our desires.26 For Calvin, we voluntarily follow our corrupt affections, but our choosing is free: “For that which is voluntary is also free.”27 In short, “man, as he was corrupted by the Fall, sinned willingly, not unwillingly or by compulsion; by the most eager inclination of his heart.”28

In light of this nuance, however, we might wonder in what sense Simon was forced to glorify the miracles of God, and whether this forcing is an exception to Calvin’s general rule that the will is not moved by compulsion. We can draw some assistance from Richard A. Muller. Calvin’s close connection between fides and cognitio makes it tempting to read him as an intellectualist, in the medieval sense. That is to say, the will is a blind follower of the intellect; hence, if the intellect judges an object as good, then the will follows suit in choosing that object. Yet, as Muller points out,

The near equation of fides and cognition in Calvin’s thought, far from solving the problem of the relationship of intellect and will, actually raises it in a rather pressing manner; for, if cognition can relate to will and to the affections of the will as well as to intellect, then fides can also have a voluntaristic as well as intellectualistic side.29

As Muller goes on to show, Calvin maintains that “the inclination toward concupiscence comes from sense and the inclination toward good from the intellect, and that—when the will follows the intellect—will may be regarded as the ‘affection of the intellect’ (affectio intellectus). Calvin subsequently states that choice belongs to the will, including the choice to follow or to disregard the intellect.”30 And again, “under ideal conditions, the free choice (liberum arbitrium) of the will becomes the basis for a decision in favor of the good known to reason rather than of the evil inclination of sense. The will ‘stands in between reason and sense’ … with the capacity to turn toward either.”31 If correct, if the will retains it power to reject the final judgment of the intellect and embrace the lower passions, then this pushes Calvin’s view into a form of voluntarism. Such voluntarism explains how the intellect might be persuaded of the good but the will still chooses contrary to the good. For such is the restricted nature of choice in our current state of depravity. Thus, “in man’s present sinful condition, the will most certainly stands prior to the intellect.”32

Despite the priority of will over intellect, Calvin does not simply delegate conversion to a change in will. True faith joins the mind and heart in faith. As Muller points out, “Calvin’s insistence on the linkage of mind and heart in faith appears to be a statement concerning the necessity of involving the whole person, or more precisely, the entire spiritual side of the person, the soul in both its faculties, intellect and will, in faith.”33 The involvement of the whole person in faith is in keeping with Calvin’s opposition to “implicit faith” in which the intellect is not involved, and, as we have seen in Calvin’s talk of the deficiencies of temporary faith, mere assent of intellect without the heart does not rise to the level of saving faith. Therefore, Muller is right in asserting that for Calvin, “It is the intellect that knows and recognizes its knowledge to be true and assents to that truth; but only when the heart or the will and its affections grasps that truth in trust can the truth be appropriated savingly by the individual.”34 This statement gets to the heart of the difficulty facing the reprobate. The intellect is won over, and the will follows to an extent, but its affections are still aimed at lower things. As Calvin comments about Judas, “the gift of regeneration is one thing, and the gift of bare intelligence, with which Judas himself was endowed, when he preached the gospel, is quite another.”35 In the reprobate, the complete soul, “the seat of the affections of the will,”36 does not give itself over to Christ; it offers only superficial affection, and the result is a transient faith that is a mean between true faith and unbelief.

The importance of these dynamics is that when we read of Simon being forced to believe or the Isrealites being overpowered by the miracles, we should not take Calvin to be offering an exception to his claim that the will acts without compulsion. Rather, Calvin has in mind a superficial winning over. Simon is forced to acknowledge the reality of divine power within the apostolic miracles that he witnessed, and the Israelites are overpowered by the reality of the works performed by God before their eyes, but in the end, these evidences yield a one-dimensional “winning over”; the reprobate’s will remains unchanged and they incapable of turning their affections toward God: “And this is to mix Christ with Satan, when doctrine pierceth not unto the hidden affections of the heart, but the inward uncleanness lieth hidden there.”37

What we find, then, is that while the reprobate has been illumined by the Spirit and heard the call to repentance and even believed, their resistance is the inevitable byproduct of an unregenerate will. Without a new will, choosing the good in the turning of the affections toward God is impossible; God may assist the unregenerate in restraining evil and even manifesting good,38 but the will must be transformed in order to truly turn to God: “Who shall say that the infirmity of the human will is strengthened by his help in order that it may aspire effectively to the choice of good, when it must rather be wholly transformed and renewed?”39 In this sense, Simon was incapable of submitting his heart to Christ, for he was illumined but not regenerate. Thus, in answer to our question, it was God’s will that Simon come to faith but only to a faith that would inevitably dissolve. In the end, the superficiality, or “hypocrisy,” of his conversion and the manifestation of that hypocrisy in apostasy was natural outgrowth of Simon’s unregenerate will. As Calvin notes in the Institutes, “after [God’s] light is removed, nothing but darkness and blindness remains. When his Spirit is taken away, our hearts harden into stones. When his guidance ceases they are wrenched into crookedness.”40

Some may find this take troubling, as if it makes God sadistic, toying with Simon—as well as any other apostates who experience temporary faith. Wouldn’t it be better to never know the truth than to be illumined only to fall away.41 What are we to make of this? Calvin offers two thoughts on this question. First, about the apostasy mentioned in Hebrews 6:4, he says the fault ultimately lies with the individual who sins: “Though this seems hard, yet there is no reason to charge God with cruelty when any one suffers only the punishment of his own defection.”42 Ultimately, the choice to reject God is symptomatic of the evil within the person, and they are rightly held accountable for it. The point does not, of course, address the fact that the person is incapable of addressing the defect in his will, but such is Calvin’s reply. Second, and perhaps more importantly, it should be kept in mind that Calvin does not see God’s dealings with a reprobate, like Simon, as arbitrary. In Book One of the Institutes, Calvin speaks about God’s purposes in the world and commends faith in the ultimate goodness of God:

… [T]he flesh incites us to contradiction, as if God were making sport of men by throwing them about like balls. It is, indeed, true that if we had quiet and composed minds ready to learn, the final outcome would show that God always has the best reason for his plan: either to instruct his own people in patience, or to correct their wicked affections and tame their lust, or to subjugate them to self-denial, or to arouse them from sluggishness; again, to bring low the proud, to shatter the cunning of the impious and to overthrow their devices…. For even though in our miseries our sins ought always to come to mind, that punishment itself may incite us to repentance, yet we see how Christ claims for the Father’s secret plan a broader justice than simply pubishing each one as he deserves.43

This picture of God’s purposes echoes in Calvin’s comments on Acts 8. Calvin ascribes purpose to the temporary faith of Simon. In the flow of the narrative of Acts, Calvin observes that Simon is a seminal figure for the Samaritans. In fact, he reads Luke as suggesting that the Samaritans viewed Simon as the manifest power of God: “Superstition made [the Samaritans] more obstinate in their error, because they counted Simon not only as a prophet of God, but even as the Spirit of God.”44 In the light of Simon’s status, Calvin suggests that winning over Simon was for the sake of the surrounding people. By convincing Simon of the gospel and the superiority of the apostolic miracles, God removed the stumbling block of Simon from the Samaritans. Calvin writes,

He which had besotted the whole city with his witchery receiveth the truth together with the others. He which had boasted himself to be the principal power of God submitteth himself to God, [Christ;] though he were brought to the knowledge of the gospel, not so much for his own sake alone, as for the whole country’s sake, that that offence might be taken out of the way which might have hindered the unskillful.45

Winnng over Simon was, on this reading, a providential act with evangelistic ends, namely, the salvation of the Samaritans. This redemptive objection was the purpose of Simon’s transient faith: “For God meant to triumph over this man, whom the Samaritans counted a petit God [Semideo].”46 Simon’s conversion turned the eyes of the Samaritans from Simon and his magic to Christ and the Holy Spirit. But because Simon was not elect, this conversion proved temporary. In short, God’s aims were not to harm Simon but to save the Samaritans.

The defense raises questions about whether Simon’s conversion was strictly necessary in order to save the Samaritans, given that regeneration is a unilateral act of God that, it would seem, could be affected by God upon the Samaritans without Simon’s conversion. Moreover, it fails to address the question of whether, despite good aims for the Samaritans, it is immortal to treat Simon as a disposable means rather than an end, as Kant might put it. Nonetheless, Calvin is satisfied to point to the salvation of the Samaritans as the divine aim that proves God’s goodness in his dealings with Simon. So, with Calvin’s take on temporary faith before us, we are in a position to consider how he deals with biblical warnings against apostasy directed at the elect.

3. Calvin on the Biblical Warnings Against Apostasy

Continued in part 3 (forthcoming).

Inst., 2.3.5.

Inst., 3.2.10.

Acts 1-13, 18:341.

Acts 1-13, 18:334.

Acts 1-13, 18:335.

Gospels, 16:101.

Acts 1-13, 18:330. See also Gospels, 16:102-4. Cf. with Calvin’s talk of the link between the word (the message of mercy) and faith in Inst., 3.2.6-7.

Acts 1-13, 18:330.

Inst., 3.2.10. Calvin points to the power that resides in the message itself simply by being a message of mercy, “For it cannot be but that so soon as we know that God will be favourable and merciful, tour minds shall be wrapt with incomparable joy.” Acts 1-13, 18:331.

Acts 1-13, 18:334; CO 48:179: veris miraculis gloriam dare cogitur. Cf. with Inst., 2.3.5; CO 2:214: hominem, ut vitiates est ex lapsu, volentem quidem peccare, non invitum nec coactum; affectione animi propensissima.

Psalms 93-150, 6:215-6.

Acts 1-13, 18:342.

Hebrews, 22:137.

Hebrews, 22:137.

Hebrews, 22:138.

Hebrews, 22:138.

Acts 1-13, 18:341-2.

Acts 1-13, 18:341.

Psalms 93-150, 6:215-6.

Inst., 2.3.5.

Inst., 2.3.5.

Inst., 2.3.5.

Inst., 2.3.5.

Calvin denies the notion that man sins out of necessity even when addressing the person of Judas, the son of perdition, who betrayed Jesus so that the Scriptures may be fulfilled. See John 12-21, 18:176-7. For an extended response by Calvin to a fatalistic use of such theology, see John Calvin, “Against the Libertines,” Robert G. Wilkie and Allen Verhey, trs., Calvin Theological Journal 15:2 (1980). In addition to the introduction by Allen Verhey accompanying this translation of “Against the Libertines,” see also Terry L. Cross, “The Yoke of Necessity: The Use of the Terms Necessitas and Coactio In the Though to John Calvin,” in The Spirit and the Mind: Essays in Informed Pentecostalism (Lanham: University Press of America, 2000), pp. 157-177, esp. p. 168ff.

Hebrews, 22:141.

I say this is a certain form of compatibilism because it is not clear that Calvin would deny the power of contrary choice in non-salvific matters. Hence, we see a compatibilistic impulse in Calvin’s defense of depravity—our choosing is still free and responsible because we did what we pleased—but it is not clear from this that Calvin would deny contrary possibilities in matters that have no bearing on salvation. Cf. Calvin, “Against the Libertines,” passim. For more on compatibilism as a model of free will (or choice), see my letter “On Free Will.” On whether the Reformed tradition advocates compatibilism, see my letter “On Predestination, John Piper, and the ‘New Calvinists’.”

Inst., 2.3.5. We may also add that Calvin makes clear that the reprobate, while sinning of necessity, but no less voluntarily, is also “bound in servitude to the devil…. This does not mean that, like unwilling slaves rightly compelled by their masters to obey, our will, although reluctant and resisting, is constrained to take orders from the devil. It means rather that the will, captivated by Satan’s wiles, of necessity obediently submits to all his leading.” Inst., 2.4.1. Thus, we may cautiously add one additional player to the scene of Acts 8. See also Inst., 2.4.2.

Inst., 2.3.5; CO 2:214: hominem, ut vitiates est ex lapsu, volentem quidem peccare, non invitum nec coactum; affectione animi propensissima.

Richard A. Muller’s “Fides and Cognitio in Relation to the Problem of Intellect and Will in the Theology of John Calvin,” Calvin Theological Journal 25 (1990), p. 211.

Muller, “Fides and Cognitio,” p. 214 (emphasis added).

Muller, “Fides and Cognitio,” p. 215.

Muller, “Fides and Cognitio,” p. 215.

Muller, “Fides and Cognitio,” p. 219.

Muller, “Fides and Cognitio,” p. 220.

1 Corinthians, 20:397.

Muller, “Fides and Cognitio,” p. 212.

Acts 1-13, 18:341.

See Inst., 2.3.3.

Inst., 2.3.6.

Inst., 2.4.4. Cf. with Acts 1-13, 18:341.

Cf. with 2 Pet 2:21.

Hebrews, 22:138.

Inst., 1.17.1.

Acts 1-13, 18:329. Calvin infers this equating of Simon with the Spirit of God from Luke’s comment, “[the Samaritans] all gave heed … saying, This man [Simon] is the great power of God.”

Acts 1-13, 18:333-4.

Acts 1-13, 18:334.