Today, the Orthodox Church commemorates the fathers of the First Ecumenical Council, the Council of Nicea held in 325 A.D. It therefore seems fitting to post something on Athanasius of Alexandria who played a pivotal role in the defeat of Arianism and the decision of that council. Toward that end, I’m posting an article I wrote on Athanasius for the forthcoming Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Christian Apologists and Their Critics.

To all my subscribers, thank you for subscribing. To my paid subscribers, thank you for your support. And to any visitors, please consider subscribing and supporting my work. Enjoy!

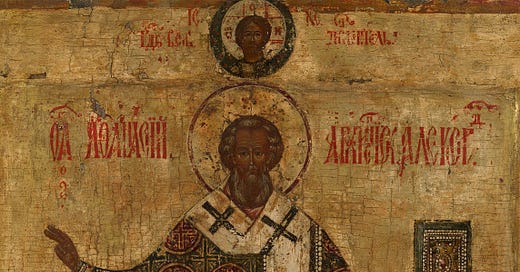

Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius of Alexandria (293-373 AD.) is one of the most important fathers of the early Christian Church. Trained in philosophy and theology in Alexandria, he served as the 20th bishop of Alexandria, successor to Alexander who died in 328 AD. The New Testament canon, used by Christians today, is often traced to Athanasius’ 39th Festal Letter of 367 AD (Athanasius 1857-88g, 1436b-40a), which lists the 27 NT books, distinguishing these inspired works from both apocryphal works of heretics and non-canonical but useful works, such as the Didache and Shepherd of Hermas. In his apologetics, he makes the case that what the pagans and the Jews each sought in their own respective ways is fulfilled in Jesus Christ. To the former, he argues that the Greek philosophers, though unearthing great wisdom, never succeeded in proliferating it; whereas Christianity spread throughout the world, successfully turning humanity from idolatry and magic, and even did so with a display of power, liberating its adherents from demonic dominion and the powers of death. To the Jews, his case is that the age of prophets, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Temple all ceased with Christ, demonstrating that he is the culmination of all of these—the fulfillment of prophecy, the true Holy of Holies, and the Eternal King (1857-88d, 152c-97).

However, for all of his contributions in these regards, Athanasius is best known for his defense of the divinity of the Son of God against the teachings of Arius. Athanasius is known as the chief opponent of the Arian view and proponent of the view upheld at the Council of Nicea in 325 AD. For his trouble, Athanasius was exiled on five separate occasions (in 336, 338, 356, 364, and 365 AD) by four different emperors (Constantine, Constantius, Julian, and Valens).

Well known is Arius’ position that the Son is a creature that came into existence at the will of the Father. Less well known is Athanasius’ insistence that Arianism carries a bevy of metaphysical entailments. An examination of Athanasius’ anti-Arian polemics makes clear that he understands the Christian faith to be metaphysically committed, and his dealings with Arius shed light on what those commitments are. More importantly, as Athanasius employs these commitments to articulate the threat of Arianism, he makes clear his uniquely Eastern understanding of Christianity.

Arianism is concisely summed up in Arius’ phrase, “there was [a time] when he [the Son] was not” (ēn pote hote ouk ēn). The case for Arianism is easily grasped. Both scripture and the Church fathers speak of Jesus Christ as God’s only begotten (monogenēs) Son. The title “son of God” may be ascribed analogically to a nation (Matt. 2:15) or to a creature, whether due to its godlike nature (Job 1:6), its adoption (Rom. 8:14), or its causal origin (Luke 2:38). Yet, in the case of Jesus, only begotten is added to the term (John 3:16), indicating that Christ is the only son whose filial status is by begetting. Despite questions by biblical scholars today about the meaning of monogenēs (see Gathercole 2006, Introduction), it was evident to both Arians and pro-Nicenes in the fourth century that the term indicates paternal causation that is singularly unique. Thus, Arius argues that the Son, being caused by God, did not exist and then came into being at the will of God, who became Father to the Son at his begetting (Socrates Scholasticus 1857-88, 42a-b).

Not surprisingly, Athanasius responds that if the Son came into being, then he is a creature. What is surprising is that Athanasius goes on to claim that it also follows from this that the Son is mutable, corruptible, accidentally good, and incapable of granting eternal life (Athanasius 1857-88b, 1097a; 1857-88e, 592b; 1857-88f, 1037b; 1857-88d, 102d; 1857-88c, 452a; 1857-88h, 21c, 29b, 49b, 57c, 72a, 84a-88a, 112c, 220a, 481d). These additional entailments are less obvious than the charge that Arius’ son of God is a creature. However, an examination of Athanasius’ polemics reveals a clear rationale for the case.

Athanasius’ argument is based on the doctrine of creation. Well known is the Christian rejection of the pagan belief that God is an artificer (dēmiourgos) that crafts the world out of pre-existent material (e.g., Plato 1929, 49c6-7; 50a4-b5, c2-6, e5-51a1, b4-6). Christianity consistently advocates, to the contrary, that God creates both the world and the matter of which it is composed. Athanasius certainly affirms creation out of nothing (ouk on), but his case against Arius introduces a different aspect of the doctrine, namely, that God calls being (to on / einai) out of non-being (mē on / einai) (e.g., Athanasius 1857-88d, 104c).

The background of Athanasius’ claim is the Jewish reception of the Aristotelian physics of generation. The ancient philosophers, especially the Eleatics, fretted over how the generation of things is possible. After all, a thing either is or is not; there is no middle. Yet, talk of “becoming” speaks as if there are gradations of existence through which a thing moves as it transitions from not-something to something (Parmenides 1951, B6.2, 7; Aristotle 1951, 191b35-192b2). Aristotle’s solution to this problem introduces the notion of potential or non-being (mē on / einai). He suggests that entities have the potential to be other than they are presently. For example, through physical exercise, I can become stronger than I am now. This potential is less than actual strength, but it is more than nothing. And this middle between nothingness and being is what accounts for the phenomenon of becoming or generation (e.g., Aristotle 1951, 192a25-33).

Aristotle’s exposition of generation brings together the concept of potential with his metaphysical realism. Realism, of course, claims that common properties, such as redness or sphericality, are real outside the mind. When we say two objects are spherical, this attribution is not a mental invention; it identifies a real property shared by the two spheres. In Aristotle’s realism, the common property is located within the object that has the given property. Sphericality is in the sphere (Aristotle 1956, 412a1-4a28; 1957, 1013a26-8; 1017b14-6; 1017b21-3; 1028b33-9a33; 1951, 192b8-3b21; 194b26-9). As for how sphericality comes to be in the sphere, Aristotle answers using the concept of potential, and here we discover his explanation of generation. Matter, Aristotle argues, is not atoms or particles but pure potential (Aristotle 1957, 1042b9-11; 1951, 190a31-b15). Generation occurs when form manifests in matter, moving material potential from non-being (or not-yet-something) into being (something) (Aristotle 2005, 317a34-320b17; 1951, 189a30-192b5; 1957, 986b10–987a2, 1046b29–1047b3). We might think of the form-matter relationship like the relationship between fabric and a solid object. The fabric is amorphous, capable of taking on any number of shapes. Were we to wrap the fabric around a ball, the fabric would become spherical. But sphericality would not belong to the fabric per se; it would belong to the ball that communicates sphericality to the fabric. In the same way, matter, as potential or non-being, is without properties of its own, but it takes on properties when form enters it. The entrance of form into matter causes matter to become a concrete something—a rock, a plant, a dog, a human—and the stages through which matter moves as it becomes something is what we call generation.

This same concept appears in Alexandrian Judaism. Philo of Alexandria employs the same terminology for generation, but he adds to it that God calls being out of non-being (ta gar mē onta ekalesen eis to einai), harkening, of course, to Genesis (Philo of Alexandria 1939, 4.187; see also 1937, 3.10; 1930 119; 1934, 1.76; 1935, 2.267; 1953, 2.13; Chadwick 1966, 44-6). Paul, too, adopts this language in his letter to the Romans (4:17), echoing not only Aristotelian physics but the Philonic addition. This addition sets these Jewish accounts apart from the pagans, both by identifying divine speech as the mode of causation and by affirming a beginning (archē) to the cosmos. (According to Aristotle, Plato was the only one of the pagan philosophers to teach that time had a beginning [Aristotle 1951, 251b16-38; Plato 1929, 38b].)

Whether from Aristotle, Philo, Paul, or some combination, the metaphysics of generation found their way into Alexandrian Christianity, and specifically into Athanasius’ polemics. In response to Arius, Athanasius argues that anything that comes to be moves from non-being (mē einai) into being (to einai). From this it follows that the thing is mutable (alloiōtos), or capable of becoming other than it is presently, since its existence began with a movement into being, which is a mutation. Therefore, anything that is created is of necessity different in nature than the immutable (analloiōtos) God (Athanasius 1857-88h, 49b; 1857-88a, 69a-72a; 1857-88e, 592b; 1857-88b, 1097a; 1857-88d, 104c). Athanasius’ description of generation is squarely in line with Aristotle, Philo, and Paul, and his claim that any start to existence involves mutation is firmly established in Aristotle’s Physics (Aristotle 1951, 192a25-33). The technical precision of the claim is also confirmed by Arius himself, who states in his defense that he does not believe the Son of God derives existence from matter (Arius 1857-88b, 212b). Arius thus understands the metaphysical underpinnings of Athanasius’ case, namely, that punctuated existence begins with a movement from non-being (i.e., material potential) into being.

Having defined creation as a movement into being, and having identified this movement as a mutation, it follows that all creatures are mutable of metaphysical necessity. Such is the basis for the Athanasian case that, granting Arianism, the Son of God is mutable. Notice that Athanasius’ case is not that God has made mutable creatures, even though he could make immutable creatures. Rather, Athanasius takes “immutable creature” to connote a contradiction beyond the bounds of omnipotence. This becomes apparent when Arius modifies his position, claiming the Father creates the Son immutable (Arius 1857-88a, 708c-9a). The change in strategy makes no difference to the pro-Nicenes, who see this “correction” as incoherent. Not even God can make four-sided circles, free creatures that are not free, or creatures that are immutable. (Athanasius complains that the Arians often shift positions, but despite their efforts to evade the charge that their “Son of God” is mutable, Athanasius never relinquishes the premise as an entailment of Arianism [Athanasius 1857-88e, 292b; 1857-88d, 102d; 1857-88h, 49b].)

Athanasius goes on to argue that mutability entails the possibility of corruption (negative change) (Athanasius 1857-88d, 104c). The rationale is rooted in the same physics. Recall that matter is pure potential, having no properties of its own. Though it can become any number of things, matter is none of the things it becomes. As in our fabric analogy, our shapeless fabric can take on sphericality, but it is not innately spherical. So in the same way, matter is a receptacle. Every property that enters it is alien to it, so any property it receives, it can also release. Therefore, anything that moves from non-being into being can return to non-being. Hence, Athanasius submits that every creature is not only mutable but corruptible.

As noted above, Athanasius draws out a host of implications beyond these, but the most important for our purposes is that if the Son is corruptible, then he is “turnable” (treptos), and if the Son is turnable, then he cannot remedy the human condition, as Christianity promises. (For a full exposition of the entailments of being created, see Jacobs 2016.) To grasp the point, we begin with the term treptos.

Treptos, as used here, refers to a mode of corruption unique to rational creatures. In organisms, corruption indicates divergence from proper formation and function, as determined by the telos of the thing. In the case of an eye, any change that moves toward sight is generation, while any retreat from sight is corruption (Aristotle 1936, 15a5-b15; 2005, 319b2-20a5). In the case of rational souls and spirits, generation and corruption is likewise determined by the telos of the creature. However, because spirits are not organisms, the change through which they move is not organic. Instead, the proper end of rational souls and spirits is spiritual in nature. The creature exists to rest in God. Any movement toward God is generation (movement into being), while any retreat from God is corruption (retreat to non-being). The susceptibility to such a retrograde movement is what Athanasius calls being “turnable” (treptos): The creature can turn away from God (Athanasius 1857-88h, 100c-101c, 117b-20a). As with mutability and corruptibility generally, Athanasius and the pro-Nicenes present this as an entailment of the Arian teaching. To quote Alexander of Alexandria’s deposition of the Arians, “when someone asked them [the Arians], whether the Word of God can possibly change as the devil changed, they were not afraid to say that he can; for being something made and created, his nature is subject to change” (Alexander 1857-88a, 573b-c; Athanasius 1857-88h, 84a-5b).

Now, the key question: Why does Athanasius understand these entailments to undermine the Christian faith? For Athanasius does not simply see these entailments as contrary to the teachings of Christianity, but as undercutting its central hope. The answer reveals Athanasius’ distinctively Eastern understanding of Christianity.

Rather than seeing the human condition through the lens of the Fall and a judicial predicament with our future judge, Athanasius sees the fundamental problem as the universal corruptibility of creatures. We have seen that the Athanasian metaphysics of creation entail that corruption threatens all that God has made, even when no creature has yet been corrupted. Hence, while corruption entered the world with the fall of angels and of humanity, this threat loomed over the cosmos from its inception. The Christian faith exists to remedy, not only manifest corruption, but corruptibility (cf. Athanasius 1857-88h, 100c-1c; 117b-20a).—This same concern echoes in Athanasius’ contemporary, Alexander, and in later fathers (e.g., Alexander 1857-88b, 552c; Gregory of Nyssa 1857-88, 1124-1269, esp. 1128a; Maximus the Confessor 1857-88a, 1057c).—So how can the threat of corruption be overcome?

The Athanasian answer, like that of other Eastern fathers, consistently points to the uncreated nature of God, which alone is incorruptible (aphthora) and unturnable (atreptos). A creature can only put off corruption—and indeed corruptibility—by partaking of divinity. On this view, the gospel of Jesus Christ offers humanity the Life of the Father (Jn. 5:29, 39-40) by communion with the divine nature, and this participation in divinity makes it possible for humanity to escape corruption (2 Pet. 1:4), putting off corruption for incorruption (1 Cor. 15:42). This is the very purpose of the Incarnation. The Son of God joined the divine nature to humanity in order that we might participate in divine life, holiness, incorruption, and so on. The view is succinctly summarized in Athanasius’ phrase, “[The Word] was made man so that we might be made God [theōpoiēthōmen]” (Athanasius 1857-88d, 192b). This is the transformation the Eastern fathers label deification (theōsis). (For similar statements, see Pseudo-Marius 1857-88, 602; Basil of Caesarea 1857-88, 109b-c; Cyril of Alexandria 1857-88, 1269; Maximus the Confessor 1857-88b, 1001b.) And this is why Athanasius finds Arianism to be so dangerous. If the Son is a creature, then he is subject to the very corruptibility that binds all creatures and cannot offer to us the incorruptible nature of God (Athanasius 1857-88h, 100c-1c; 117b-20a).

So what does Athanasius mean when he speaks of us being made God? The answer, again, draws on Pauline and Alexandrian Jewish echoes of Aristotelian physics. Paul often speaks of being “energized” by God (e.g., Phil. 2:13; Col. 1:29; Gal. 2:8) (see Bradshaw 2006). The term energeia has a long history in Aristotle, Alexandrian Judaism, and the New Testament, a history that informs the Eastern Church fathers (see Bradshaw 2004, passim). The term originates with Aristotle, initially as a point of physics and later with theological significance in his cosmological argument (Bradshaw 2004, chapter 1). In the hands of religious writers, two crucial developments followed. First, there emerged a distinction between God’s essence (ousia) and his energies (energeiai) (e.g., Philo of Alexandria 1929, 89-90; Pseudo-Aristeas 1951, §266). Second, as David Bradshaw explains, “the term acquires a new sense of ‘active power’ or ‘cosmic force,’ and eventually ‘energy,’ conceived not just as a characteristic of action … but as a reservoir of power that can be shared by another” (Bradshaw 2004, 119). These developments inform how these writers understand the intersection between spirits and humans. Demoniacs perform superhuman feats because they are energized by a foreign nature. Likewise, prophets, apostles, and saints do miraculous deeds because they are energized by God.

A favorite analogy of the Eastern fathers to explain the energizing of a person is the communion between metal and fire. Fire can heat metal to a point that it glows and burns even after its removal from the flames. The metal remains metal, but the energies of a foreign nature—of fire—have taken up residence within it (e.g., Basil of Caesarea 1857-88, 136a-137b; John of Damascus 1857-88, 1046c-61d; 1068b-72b). So in the same way, the human person, though remaining human in nature, partakes of or participates in the divine nature when energized by God. Such participation is what Athanasius means by being made God, and he understands it to be the purpose for which the Word was made flesh. This is the understanding of the faith Athanasius dedicated his life to defending, a defense ultimately vindicated at the Council of Nicea in 325 AD.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Alexander of Alexandria. 1857-88a. Epistolae de Ariana haeresi deque Arii depositione. In Migne, J.P. (ed.), Patrologiae Graeca, 161 vols. Paris: Imprimerie Catholique. Vol. 18.

_____. 1857-88b. Epistula ad Alexandrum Constantinopolitanum. In PG. Vol. 18.

Aristotle. 1933. Metaphysics. In LCL. Vol. 271.

_____. 1934. Physics, Volume II: Books 5-8. In Loeb Classical Library. Henderson, Jeffrey (gen ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Vols. 228.

_____. 1938. Categories. In LCL. Vol. 235.

_____. 1955. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. In LCL. Vol. 400.

_____. 1957a. On the Soul. In LCL. Vol. 288.

_____. 1957b. Physics, Volume I: Books 1-4. In LCL. Vol. 255.

Arius of Alexandria. 1857-88a. Epistola ad Alexandrum papam. In PG. Vol. 26.

_____. 1857-88b. Epistula ad Eusebium Nicomediensem. In PG. Vol. 42.

Athanasius of Alexandria. 1857-88a. Contra gentes. In PG. Vol. 25.

_____. 1857-88b. De incarnatione Domini contra Apollinarium. In PG. Vol. 26.

_____. 1857-88c. De decretis Nicaenae synodi. In PG. Vol. 25.

_____. 1857-88d. De incarnatione Verbi. In PG. Vol. 25.

_____. 1857-88e. Epistula ad Serapionem. In PG. Vol. 26.

_____. 1857-88f. Epistula ad Afros Epistopos. In PG. Vol. 26.

_____. 1857-88g. Epistolae Festales XXXIX. In PG. Vol. 26.

_____. 1857-88h. Orationes tres adversus Arianos. In PG. Vol. 26.

Basil of Caesarea. 1857-88. De Spiritu Sancto. In PG. Vol. 32.

Gregory of Nyssa. 1857-88. Adversus Apollinarem. In PG. Vol. 45.

John of Damascus. 1857-88. Expositio fidei orthodoxae. In PG. Vol. 94.

Maximus the Confessor. 1857-88a. Ambigua. In PG. Vol. 91.

_____. 1857-88b. De charitate centuria. In PG. Vol. 90.

Parmenides. 1951. Fragments. In Diels, H. and W. Kranz (ed.), Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, 6th ed. Berlin: Weidmann.

Philo of Alexandria. 1929. On the Cherubim, the Flaming Sword, and Cain. In LCL. Vol. 227.

_____. 1930. On the Unchangeableness of God. In LCL. Vol. 247.

_____. 1934. On Dreams. In LCL. Vol. 275.

_____. 1935. On Moses. In LCL. Vol. 289.

_____. 1937. On Special Laws, Books 1-3. In LCL. Vols. 320.

_____. 1939. On Special Laws, Books 4. In LCL. Vols. 341.

_____. 1953. Questions on Genesis. In LCL. Vol. 380.

Plato. 1929. Timaeus. In LCL. Vol. 234.

Pseudo-Aristeas. 1951. Letter to Philocrates. Moses Hadas (ed.). New York: Harper & Brothers.

Pseudo-Macarius. 1857-88. Homiliae. In PG. Vol. 34.

Socrates Scholasticus. 1857-88. Historia ecclesiastica. In PG. Vol. 67.

Secondary Sources

Bradshaw, David. 2004. Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

_____. 2006. “The Divine Energies in the New Testament.” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 50: 189-223.

Chadwick, H. 1966. Early Christian Thought and the Classical Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gathercole, S. J. 2006. The Pre-Existent Son. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Jacobs, Nathan A. 2016. “On the Metaphysics of God and Creatures in the Eastern Pro-Nicenes.” Philosophy & Theology 28.1: 3-42.